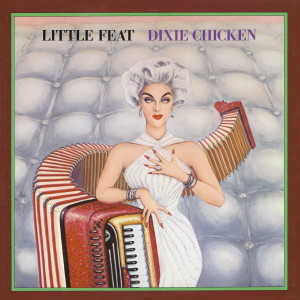

Little Feat – Dixie Chicken Warner Bros. BS 2686 (1973)

All things considered, Dixie Chicken is probably the best place to start with Little Feat. The group’s sound was well defined by this point. The eccentric characters and stories of “Dixie Chicken” and “Fat Man in the Bathtub” sit well with the nice ballads “Roll Um Easy” and “Fool Yourself” and the increasingly boogie-rock oriented material like “Two Trains” and “Walkin’ All Night.” Lowell George, the group’s star and best songwriter, guitarist, and singer, was still a major force on this album, before he started to fade away from the spotlight in the coming years. From here, go back to the previous album Sailin’ Shoes, which is more eccentric and is even better, or, if the slicker, more boogie-oriented stuff is more to your liking, head for Little Feat’s next album Feats Don’t Fail Me Now.

When I was involved with college radio, there was a very explicit idea conveyed to everyone at the station that you needed to play music outside of what you could hear on typical commercial radio. Whenever classic rock or 1970s rock in general was mentioned, Little Feat was a common example of what was okay to play, as being a band generally overlooked. This always caught my attention, because in high school I had come across Little Feat and a few of their records that I had were favorites that I played over and over. Now, I don’t mean to imply that classic rock stations didn’t play Little Feat — I had heard “Dixie Chicken” on the radio before, on a rare occasion, but that was only when a station had some kind of marathon event where it played one song by every artist in its library. The basic point here is that Little Feat never quite clicked with a huge audience for whatever reason. But they clicked with me early on. Fast forward quite some time and I find myself still listening to and enjoying the music of Little Feat.