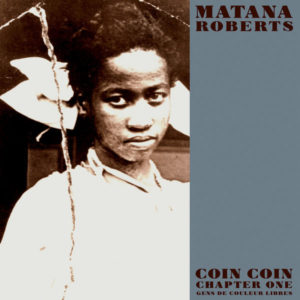

Matana Roberts – Coin Coin Chapter One: Gens de couleur libres Constellation CST079-2 (2011)

Well, this might well be the epitome of how identity politics represents a dead end. Coin Coin Chapter One is a concept album that develops a stigmatizing identity of the oppressed that (here’s the rub) polarizes others into either racist oppressors or friendly consumers of exotic otherness made possible by an enriching sense of difference (though primarily directed to the latter as an audience). It shuts the door to universality. It also pines for a false authenticity. Rather than working to create a kind of genuine, material emancipation in the present, this music dwells on the loss of the past and the wounds of history. Set aside slavery, and weren’t white women routinely oppressed in the antebellum era too? Aside from the obviously horrible brutality of human bondage, the problem of slavery was not the denial of the rights on the basis of skin color but the vacuousness of the “free” people who accepted (or even tolerated) oppression and considered themselves society’s “betters” under such circumstances. And does this all overlook how the cultures destroyed by chattel slavery (as much as any others) were meaningless, arbitrary human constructs? And isn’t condemning slavery kind of an easy thing in modern times? Even if it does still exist today in the dark corners, who really openly argues for it? Today the more appropriate question is to ask why more resources are not devoted to completely eradicating such an acknowledged evil — or why consensual activity is conflated with “human trafficking” to artificially inflate the numbers. More broadly, the task is to struggle to make concrete the freedoms everyone acknowledges as essential but are hypocritically denied in fact in so many ways. Short of those specifics, even looking to the “free your mind and your ass will follow” approach, what is needed, as Alejandro Jodorowsky once wrote, is “to undergo a mental cataclysm that causes our worldview, our psychic stance, and any sort of self-concept to crumble, precipitating us into the void — a void that engenders us, enabling us to be reborn freer than before and, for the first time, to be in the world as it is instead of as we have learned it is.” This is not accomplished by Coin Coin Chapter One. In fact, it pursues something quite the opposite — isn’t at some level this commercially released album a way of profiting off (the history of) slavery and oppression? Is the past not being called up to reinforce a feeling of victimhood status as the essential element of a lasting identity? Give that some thought.

Anyway, the album itself is part free jazz part hard bop jazz, part singing and part spoken word, all rendered in a dramatic way. In fact, a useful reference point would be the “audiodramas” of Julius Hemphill (Roi Boyé & the Gotham Minstrels, etc.) — to a lesser extent also the jazz operas of Fred Ho. The thing is, those things have been done, and, even including her specific performance styles that look to other influences, Roberts is merely approximating styles of her forebears. So in spite of the generally excellent execution, this album is a giant, smug pat on the back to the friendly consumers of exotic otherness who pride themselves on endorsing freedom and such feel-good principles — the same approach taken by groups like Sweet Honey in the Rock, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, etc. Coin Coin Chapter One isn’t a failure, entirely or exactly, but it is appropriately a compromised, self-contradictory mess, and in many ways presents a seductive trap of suggesting that all that is possible is to feel sorry about the wrongs of the past (from a rather insular and singular perspective) to eliminate only the very worst atrocities, quietly shutting the door to opportunities to provide and expand more general emancipation today (in the sense of Fanon). This has a Foucault-ian, historicist, fundamentalist, neoliberal, “there is no alternative” kind of vibe lurking just outside its own frame. So, strangely, this is an album that feels like it wins every battle, song by song and note by note, yet loses the war — because it fights the wrong war, one that is totally inadequate.