Gladys Knight & The Pips – Neither One of Us Soul S 737L (1973)

The early 1970s were an interesting time for soul music. The genre underwent seismic shifts. Those musical shifts went along with shifting social circumstances. As the liberal “freedom movement” (AKA “civil rights movement”) stepped back following its “victories” (which proved small and mostly temporary), and as severe backlash (including torture and assassinations) against anti-capitalist black militancy set in, there was a kind of metaphorical fork in the road. The best and brightest black Americans could accede to the dictates of the establishment, forsake the “movement” in exchange for narrow personal benefit, or, instead, commit to solidarity with a large class-based coalition in spite of the scorn and repression of the vested interests and all their concomitant tactics of racial bigotry. So take the title track, “Neither One of Us (Wants to Be the First to Say Goodbye).” There is a long tradition in black music of “masking,” with two meanings embedded in songs (usually one light and often romantic, the other socio-political and often dealing with racism). The title song could be seen as being about the decision point as the freedom movement and black militancy were receding and facing real defeats — in the face of state violence in the form of COINTELPRO and the like. Stick with it or turn one’s back on it and say goodbye? The song is brilliant, and one of Knight & The Pips’ best recorded performances, up there with their later hit “Midnight Train to Georgia.”

A lot of soul music in the early-/mid-70s drew on a sense of urban elitism. Adolph Reed is one of the best commentators on that phenomenon, asserting that “race politics is not an alternative to class politics; it is a class politics, the politics of the left-wing of neoliberalism. *** As I have argued, following Walter Michaels and others, within that moral economy a society in which 1% of the population controlled 90% of the resources could be just, provided that roughly 12% of the 1% were black, 12% were Latino, 50% were women, and whatever the appropriate proportions were LGBT people.” Or as Pete Dolack put it, “liberal ideology tends to fight for the ability of minorities and women to be able to obtain elite jobs as ends to themselves rather than orient toward a larger struggle against systemic inequality and oppression. *** A movement serious about change fights structural discrimination; it doesn’t fight for a few individuals to have a career.” The upshot of the now-prevailing neoliberal mindset is that so long as a representative proportion of racial minorities are given privileged positions in a system of stark and brutal inequality then the all forms of social activism aimed at the larger, systemic and institutional inequalities are deemed inappropriate, even invalid. This sort of undercurrent flows through a lot of “Philly Soul”, which could seem a bit opportunistic and self-congratulatory. But Neither One of Us conveys a deeper sense of conflict. It was poised right at the historical juncture when different paths forward were possible, and people, in essence, had to collectively and individually choose their path. It may not be explicit about it, but the album is chock full of a sense of apprehension about the future. Gladys Knight & The Pips were deftly conveying that sense of the times, as were a few others like Sly Stone (Fresh).

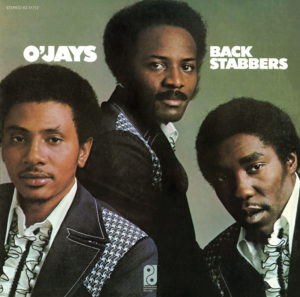

The arrangements and production on Neither One of Us are by an army of supporting personnel — six producers and eight arrangers! But it works damn well. Just check the phenomenal “This Child Needs Its Father,” opening with a seductively lethargic melodic line played on strings and a growing element of psychedelic guitar. Contrast the limp and boilerplate strings on O’Jays‘ Back Stabbers from the same year, which seem to simply magnify a single idea across many string players rather than using the orchestration to build something premised on the interactions of a multitude of players. This difference is precisely that between the urban liberal “there is no alternative” attitude exemplified by the formulaic, immutable and homophonic orchestrations of the O’Jays, on the one hand, and the more diffuse egalitarianism represented by the sort of interactive, layered orchestration on “This Child Needs Its Father” (or, say, early 1970s recordings of Curtis Mayfield), on the other.

This is a great one, up there with the very best Motown-affiliated LPs, like David Ruffin‘s My Whole World Ended, Marvin Gaye‘s What’s Going On, and Stevie Wonder‘s best few albums.