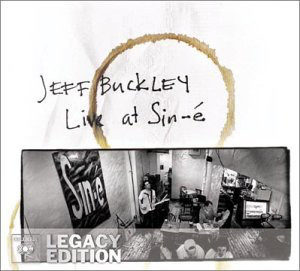

Jeff Buckley – Live at Sin-é: Legacy Edition Legacy C2K 89202 (2003)

Before landing a major-label record deal, Jeff Buckley spent time doing gigs at coffee shops and other mostly small venues in New York’s lower east side. He referred to these as his “cafe days”. After inking that contract, the label recorded him (in hi fidelity) live in July and August 1993 at one of his favorite “cafe days” venues: Sin-é (a Gaelic phrase pronounced “shin-aye”). The venue was tiny. As pictured on the album cover, Buckley was basically set up in a corner, without any kind of stage riser, so close to the audience that he might hit somebody with his guitar neck if not careful. Originally released as a four-song EP in late 1993, a little less than a year before his full-length studio debut album Grace, this was kind of a tribute document to an important phase of Buckley’s career that was coming to an end, as well as a teaser to drum up interest in what was to come. In 2003, an expanded “Legacy Edition” was posthumously released, featuring two full CDs and a short DVD (only some of the DVD content is from Sin-é, though, recorded in 1996).

The performances are as intimate as the venue. This is just Buckley, alone, playing electric guitar and singing. His performances have all the wistful romanticism that would make him a cult star in the coming years — before his untimely death by drowning at age 30. In the Legacy Edition liner notes (all quite well-composed and informative, incidentally), Mitchell Cohen calls Buckley’s approach a “daredevil’s cabaret”. It is precisely the right term. Buckley has a very earnest — almost naïve — ambition that totally undermines what would otherwise be called pretension. Yet he still puts himself in the spotlight and strives for recognition. He is going for a kind of intuitive and personal bohemian ethos that, above all, is driven by emotion. But he relies on a curious kind of pensive and introverted feeling, looking as much to the future and its possibilities as it does the vagaries of the immediate present. It may not be the sort of thing that appeals to everyone, but Buckley’s fans tend to find his style uniquely appealing.

Buckley’s music cut against the commercial trends of the day. At a time when morose and almost nihilistic rock, with “raw” vocals, was dominant — think “Grunge” rock acts like Nirvana — Buckley was instead developing a repertoire that looked backwards to pop, folk, blues and religious music of the by-gone past, combined with his own songs that leaned on urbanized, mystical pop blues. He also sang with a decidedly “traditional pop” style of vibrato, like old time bel canto singing derived from opera (epitomized by Édith Piaf, etc.). While there are a few popular singers who have used substantial vibrato in the rock era, like Bryan Ferry of Roxy Music, Joan Baez, and Jeff’s biological father Tim Buckley, it was increasingly rare. It gives the music its own incongruous sophistication.

All of the best songs from Grace are here. That includes a performance of John Cale‘s compact arrangement of Leonard Cohen‘s “Hallelujah,” which became Buckley’s signature song. Quite surprisingly, even as solo performances the arrangements are basically the same as on the later studio recordings. But in place of the slightly ill-fitting clinical professionalism of the studio band, there is the more immediate charm in Buckley’s do-it-yourself one man performance. As another reviewer astutely put it, “The performances range from amazing to alright and everything in between. The flaws only make it more endearing, though.”

As to the Legacy Edition, disc one is the better of the two. Though both have much to offer. Buckley wears his influences on his sleeve. There are choice covers. The second disc slows a bit, due to between-song narratives that seem to go on longer, and a few of the less successful performances are more grating. Buckley declares himself an unabashed Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan superfan, but his performance of “Yeh jo halka halka saroor hai” induces cringes. It proves — should such proof be necessary — that Buckley knew Kahn songs by heart, but his voice just isn’t up to the task of qawwali devotional singing. But for every moment like that, there are two or three like “I Shall Be Released” and “Be My Husband,” where Buckley gives his own memorable take on an iconic song.

In an interview on the DVD, Buckley suggests that he has much more and better things on the way. Yet, really, Live at Sin-é: Legacy Edition is already Buckley at his best — not his most polished, but his best. Here he is willing to try things that he is not certain will work. There is a tentative — and, if you will, “contingent” — quality to this that is absent on his studio recordings. Those qualities end up being bigger assets than the polish and precision of the later studio recordings (even if Gary Lucas does add intriguing guitar work in places on Grace).

There is much to like about Live at Sin-é: Legacy Edition. Listeners can admire Buckley’s efforts to succeed through hard work and determination. They can appreciate his efforts to find continuity with the past while also looking to grow and evolve. There is also his impish charm and convincing emoting. And the song selection is hard to argue with. Any which way, this collection remains a valuable document of some of the best of what was musically possible in one particular place and time.