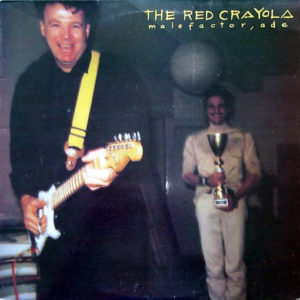

The Red Crayola – Malefactor, Ade Glass GLALP 035 (1989)

Malefactor, Ade is a bit of an odd album even in the catalog of a band that was strange from the very beginning. On the one hand, parts of this bear resemblances to the “performance art” music of Laurie Anderson, the open-minded ambitions of the so-called “Rock in Opposition” bands, and there are still remnants of the funky no-wave punk that The Red Crayola had pursued (often in collaboration with the art collective Art & Language) over the prior decade, now more minimalist in delivery. But on the other hand, this is music that is built up from surprisingly non-musical elements. Often these songs are just a bunch of bloops, bleeps and banging, with sing-speak vocals on top, a single guitar and some drums or cheap synthesizer keyboards that point towards melody, or the semblance of melody. The lyrics draw on non-sequitur humor. This points towards an effort to place the musical and the non-musical on equal footing — a nod towards a universalist political philosophy. These sorts of elements also point toward the music made by the re-formed group (back under the spelling Red Krayola) in the United States in the mid-1990s, which was more surrealist and linked to the “post-rock” scene. There are some “jazzier” instrumental bits too. So, this should be viewed as a transitional album. This is one more for the converted than newcomers, but it is a solid little album and one that is much better than its reputation suggests.