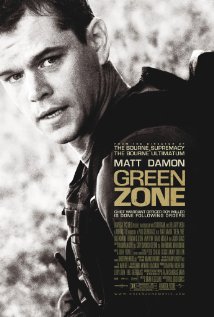

Green Zone (2010)

Universal Pictures

Director: Paul Greengrass

Main Cast: Matt Damon, Greg Kinnear

Some movies about the Unites States’ second war against former ally Iraq focus exclusively on the bravery, hardships, misfortunes, valor, and other personal experiences of the soldiers. Examples are The Hurt Locker (2008) and Stop-Loss (2008). These sorts of films make no attempt whatsoever to contextualize the war. In The Hurt Locker, the main characters diffuse improvised explosive devices throughout the entire movie. Why are those bombs being made and planted in the first place? The movie doesn’t even entertain that question.

Green Zone falls into another category of films that try to explain what the war was about. Another example in this category is Redacted (2007). Green Zone is loosely inspired by journalist Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s book Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone (2006), which provided an account of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) that the U.S. government installed in a heavily fortified city-within-a-city in Baghdad during the war (until June 2004, when the Green Zone was handed over to the U.S. State Department). The script for Green Zone, however, is fictional. Paul Bremer, the incompetent neo-con and Henry Kissinger protégé in charge of the CPA (after Lieutenant General Jay Garner was abruptly fired) is fictionalized as Clark Poundstone (Greg Kinnear). Chief Warrant Office Roy Miller (Matt Damon) is an outrageously superhero-like soldier who seeks the truth about the war, when his missions to secure materials for weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) turn up nothing and he suspects bad intelligence.

The plot is far-fetched, and the timeline historically inaccurate. Still, the movie has somewhat decent intentions. Drawing from Chandrasekaran’s book are the major points that Bremer & Co.’s decisions to implement #1 De-Ba’athification (removal of all government officials from Saddam Hussein’s socialist party) and #2 dissolution of the Iraqi Army were monumentally bad decisions, and the idea that the folks in the Green Zone calling the shots lived in a bubble divorced entirely from the facts on the ground outside the well-protected green zone perimeter. Even in 2014, a decade later, Bremer continues to defend what he did, going so far as to call dissolution of the Iraqi army the best decision he made with the CPA (Losing Iraq). The movie positions the CIA agent Martin “Marty” Brown (Brendan Gleeson) as a counterpoint figure. There, the script admirably tries to portray the U.S. government not as a monolithic entity, but subject to competing factions within it, complete with individuals vying for personal advancement and inter-agency turf battles. There are also heavy-handed attempts to provide an Iraqi perspective, mostly by way of a former Iraqi soldier nicknamed “Freddy” (Khalid Abdalla). But in spite of those attempts, the plot lurches from one action movie cliché to the next.

Director Paul Greengrass also directed Damon in two Bourne movies, and there are a few too many parallels here for comfort. There are extended chase scenes filmed with shaky portable cameras and Damon’s character always seems to be a step ahead in ways that strain credibility. Also, Kinnear has a lackey in the army who unflinchingly carries out orders, even when those include taking out fellow U.S. soldiers. That is possible, but these soldiers are portrayed as one-dimensional robots, as if Damon’s character is the only soldier in the army with a conscience. These features create plot situations that clearly lack authenticity. The tone is frequently of Damon’s character as a truth-machine, pitted against a monster in Kinnear. This is a little too simple. Chandrasekaran portrayed the CPA as a corrupt organization that placed loyalty to George W. Bush and his GOP party above actual qualifications or good decision-making. The later book by Peter Van Buren, We Meant Well (2011), which focused on the U.S. State Department’s bungled, ridiculous efforts at “reconstruction” of Iraq in 2009-10, demonstrates how that same mindset also took hold in the State Department. It wasn’t a “few bad apples”, it was a spectacle of an immensely and widely corrupt U.S. government trying to “liberate” Iraq from its corrupt government that hardly seemed any different!

This film deserves credit for trying to imbue a Hollywood movie with a realistic perspective of what happened to cause the Iraq war to proceed as it did. But it also deserves derision for being contrived and implausible, a failure of technique and writing mostly, which directly undermines all attempts to paint an accurate picture of the war.