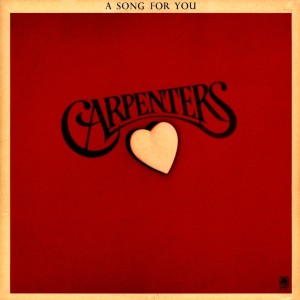

Carpenters – A Song for You A&M Records SP-3511 (1972)

The Carpenters have a reputation for being safe popular music. How wrong! Like F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby (1925) is so often described as telling the story of the empty heart of the jazz age, so the Carpenters made music that revealed dark and empty places inside a lifestyle with all the appearance of success. Loneliness, heartbreak, alienation are the hard core of that success. As another reviewer put it, “Not only does Karen Carpenter sing like a wounded angel through out, but their famously exquisite harmonies both purr and soar like you wouldn’t believe.”

A Song for You is considered by many fans to be the duo’s finest album. The first side is for Karen. Her voice is the centerpiece. This, however, is no surprise. Her voice was always the most brilliant feature of all the Carpenters’ hits. Side two, though, is for Richard. He was a talented arranger. Across the album, without being showy or gratuitous, he manages to work in a saxophone solo, a flute solo, an electric guitar solo, layers of acoustic piano and Wurlitzer electric piano, strings, and more. As to the “more,” his biggest stroke of genius is the use of an oboe and cor anglais. Playing sweet melodies, as on “Goodbye to Love,” the woody yet sour timbre of the instruments are the ideal expression of the emotional tone of numerous songs on the album. The instrumental “Flat Baroque” builds from (as the title implies) a baroque chamber pop song to include touches of light jazz. Later on, “Crystal Lullaby” has more Euro-classical orchestration. Then “Road Ode” displays a faculty for convincing contemporary, orchestrated pop jazz (like Antonio Carlos Jobim‘s Wave). “Top of the World” is country — this album version sounds more country than the single version. If there is a glaring flaw anywhere, it is the latin easy listening horn arrangements that arrive in jarring fashion in a few places.

Maybe it is because I was reading Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s St. Paul: A Screenplay, which somehow counseled listening to A Song For You, but there is a way to consider this as a “concept album” statement in atheism. This is especially pronounced when listening to “Goodbye to Love”. Intellectuals have adopted this idea that atheism takes on specific meaning when it comes from christian teachings — these people sometimes call themselves “christian atheists”. Martin Scorsese‘s film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), based on Nikos Kazantzakis‘ book, ends with this sort of a view. Jesus, dying from crucifixion, asks, “Father, why have you forsaken me?” Then he dies, without being saved from death by a god that doesn’t exist, realizing — and teaching — that everyone must learn that no god will guarantee meaning to our lives and we are each alone with our own freedom. This is precisely what “Goodbye to Love” can be read as saying. “Love” is, of course, the foundation of christian faith and religion, a resolution for an abyss of unknowing. And A Song For You has references to christian themes in other songs like “Top of the World,” “Interlude” and “Bless the Beasts and Children.” So, it is fair to read this song as referencing christian values of love. The songs lyrics include: “No one ever cared if I should live or die . . . So I’ve made my mind up I must live my life alone . . . From this day love is forgotten, I’ll go on as best I can.” What is this, Samuel Beckett? There are traces of agnosticism in the lines, “What lies in the future is a mystery to us all / no one can predict the wheel of fortune as it falls / there may come a time when I will see that I’ve been wrong / but for now this is my song and it’s goodbye to love.” But, still, the core of the song deals with how to live without love, without resolution to the “years of useless search” to know what “god” wanted (or wants) from the protagonist. After all, the lyrics already suggest that “no one ever cared,” which must be treated as saying not even “god” cared. If this is the devastating, subjective destitution of “Goodbye to Love,” then it is important to look to the rest of the album to find out what use this atheistic freedom is put to use toward. I think it comes through on side two, and especially from the reprise of the title song concluding the album.

It is significant that “Goodbye to Love” is, aside from a brief half-joke hymn in “Intermission,” at the close of the first side of the album. It represents the final loss of faith that was tested and crumbling already. So, the song “Hurting Each Other” follows “Top of the World.” There is no doubt that “Top of the World” is about finding love. It is the most buoyant song on the entire album. But, it is immediately followed by “Hurting Each Other,” which is about a kind of broken relationship, going on while the couple wounds each other. Then “It’s Going to Take Some Time” implies a breakup, with questioning as to how amends could be made. By the time we reach “Goodbye to Love,” there is a crash, a shattering that plays out to take away the faith that was once present. Side two of the album is about a search for something to take the place of that absent faith. “I Won’t Last a Day Without You,” “Bless the Beasts and Children” and “Road Ode,” even “Piano Picker” too, are interesting in this respect. They sort of pull together aspects of things that were present before the crisis of faith, but gives them new significance in the absence of faith. “Piano Picker,” with Richard singing, may be the clumsiest of them, but the song deals with a re-framing of what was in his childhood and young adulthood considered a lack — not being a popular “jock” athlete but instead being alone practicing the piano — and reconstitutes it as a core of what makes the protagonist someone with something to objectively contribute to the world. “Bless the Beasts and Children” and “Crystal Lullaby” both kind of map out aspirations to care for future generations and animals, the most meek and vulnerable (classic themes from christianity).

“I Won’t Last a Day Without You” could be the most problematic song for my interpretation of the album. It follows the very atheistic theme that the scariest thing in the world is the otherness of strangers. But the refrain goes: “I can take all the madness the world has to give / but I won’t last a day without you.” From one angle, this has the trappings of a Jesus song. Yet, if we commit to my interpretation of the album as a whole, maybe the song can be read along those lines, as being about the sense of collective emancipatory potential in non-divine personal relationships. That is, the power of two is collectively greater than what the power of one, alone, can withstand. In a foreword to an edition of the Pasolini St. Paul screenplay, philosopher Alain Badiou notes:

“In our world, in fact, truth can only make its way by protecting itself from the corrupted outside, and establishing, within this protection, an iron discipline that enables it to ‘come out’, to turn actively towards the exterior, without fearing to lose itself in this. The whole problem is that this discipline . . . , although totally necessary, is also tendentially incompatible with the pureness of True. Rivalries, betrayals, struggles for power, routine, silent acceptance of the external corruption under the cover of practical ‘realism’: all this means that the spirit which created the Church no longer recognizes in it, or only with great difficulty, that in the name of which it was created.”

In the song, at least the line “when there’s no getting over that rainbow” might confirm that we are dealing with human social relations, and not divine interventions. Still, this can be viewed as forming relationships for protection, in pursuit of something greater. In the christian world this is the “holy spirit”. If the album makes this point somewhat inconsistently, then it may be the expression of just what Badiou sees as the inconsistency in Pasolini’s St. Paul.

All of this comes full circle at the close, reprising Leon Russell‘s “A Song for You.” A song reprise or prelude can often be a lazy attempt to extend the appeal of a single song through rote duplication. But here, the closing “A Song for You (Reprise)” is more than that. It opens with Karen’s voice, eerie, echoed and only faintly audible — it almost requires turning the volume up to even hear it at all. It soon enough swells to the familiar song that opens the album. Yet the context is now entirely different. After all these songs about crushing pain, heartbreak and loneliness there is still room to return to “singing a song for you.” Significantly, the reprise omits the first part of the song lyrics that first speak of having “ten thousand people watching” but turning away toward a situation in which “we’re alone now.” It instead goes straight to the end of the song, dealing with “when my life is over remember when we were together / we were alone and I was singing this song for you.” Only here, at the end of the album, can the meaning of the opening song be grasped. It was only after the loss of faith, and the recognition that there is no external force to supply meaning, can the protagonist find meaning in being with others and singing. By doing this in a way that returns to the opening song, a cycle is explicitly created. We return to where we began, but with new understanding after the exhaustion and failures contained within the cycle. So even though the album opens dealing with personal relationships, and ends dealing with personal relationships, it goes from being about false, empty relationships to at least understanding better what makes for meaningful, real ones. It allows, at the core, for a process of recognizing a lack of (meaningful, real) relationships, and sets out to try to provide them, if only symbolically.

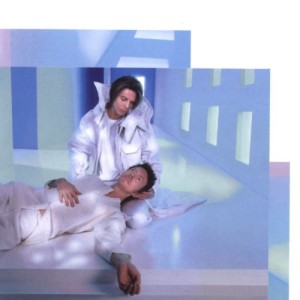

Didn’t think there was so much to find in a Carpenters album, a group often dismissed as saccharine, safe and boring? In a way, this is revolutionary music. There is definitely more to the brother-sister duo than appears upon a quick glance at their publicity photos that always assure the viewer of their protestant modesty. Look at the liner sleeve that accompanied the original album pressing, printed on “100% recycled paper” as “an anti-pollutionary measure” and replete with slightly ironic cartoon illustrations paired with some of the song lyrics. The real-life Carpenters didn’t manage to hold out the way this album suggests (it is play acting, as the line about going off to the bathroom in “Interlude” establishes). But, indie-rock band Sonic Youth‘s bassist Kim Gordon — an unabashed Carpenters fan — wrote a posthumous open letter to Karen Carpenter re-printed in Sonic Youth etc.: Sensational Fix (2009). She asked, “Who is Karen Carpenter, really, besides the sad girl with the extraordinarily beautiful, soulful voice?” Karen famously died from complications of an eating disorder. Richard had drug problems. Much like Elvis, the Carpenters were crushed under a weighty touring schedule. And just like Pasolini’s view of St. Paul forming the christian church, touring robbed the Carpenters of the music that was their truth and purpose to begin with. But, as listeners, we should not overlook what was there at the start, the kernel of emancipatory potential wrapped in the clothes of the most claustrophobic, conformist MOR pop music of the early 1970s. If this music can appeal to listeners who want sentimental music while at the same time have substantial value under a totally unsentimental interpretation, then A Song for You does transgresses boundaries in a radical way.