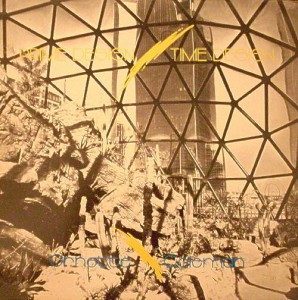

Ornette Coleman – Prime Design / Time Design Caravan of Dreams CDP 85002 (1986)

Ornette Coleman met futurist/architect/inventor R. Buckminster Fuller in 1982, after first attending one of his lectures in Los Angeles back in 1954. In an interview included in the film Ornette: Made in America, Ornette calls Fuller his “number one hero.” After the 1982 meeting, Ornette told Kathelin Hoffman Gray, the artistic director of the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth, Texas, that he had to write something for Fuller. That composition ended up being Prime Design / Time Design. Ornette also wrote another tribute to Fuller that appears on the bootleg Reunion 1990.

Fuller is perhaps most widely known as the popularizer of geodesic domes. But he also invented the Fuller Projection map (the most visually accurate flat representation of the Earth) and “tensegrity” structures used in bridge design, coined the phrase “Spaceship Earth”, developed the “World Game” simulation, participated in the “Dartmouth Conferences”, designed an experimental city (never constructed) called “Old Man River’s City” and (never constructed) floating-in-water apartment complexes, and advocated for a global electricity grid (something slowly inching toward realization). He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1983. In his book Critical Path, he claimed, “I am apolitical and an ardent advocate of an omnihumanity-advantaging freedom of individual initiative . . . .” and described one of his early life goals as to be a kind of Robin Hood armed with scientific textbooks, microscopes and calculators instead of a longbow and staff. One of Fuller’s famous quotes is, “If success or failure of this planet and of human beings depended on how I am and what I do… HOW WOULD I BE? WHAT WOULD I DO?” Fuller operated in a way often parallel to Technocracy Incorporated, the radical era of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), and Veblen‘s essays collected in The Engineers and the Price System, though Fuller wasn’t ever a part of those organizations or directly linked to Veblen. He did, however, explicitly subscribe to Count Alfred Korzybski‘s “General Semantics”, documented in a 1933 book Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics but mostly promoted through lectures (which Fuller attended, as did beat writer and Coleman acquaintance William S. Burroughs).

General Semantics was intended to offer a synthesis of all human knowledge. Mostly, though, the focus was on the imprecision of language, and a rejection of dualistic essentialism and extrovert bias. Korzybski’s most famous saying was that “the map is not the territory”, which is similar to Saussure‘s formulation in semiotics that the signifier is not the signified. Something like this is also involved in the analysis of chains of signifiers in psychoanalysis. William S. Burroughs (a strong adherent to psychoanalysis) often recalled to interviewers how Korzybski would start his lectures by banging his hand on a table and saying, “Whatever this is, it is not a table.” What he meant was that the word “table” referred to the thing he had just banged his hand on, but the word was not the thing itself. A funny aspect of this is that in a later-life interview included in the book The Jazz Ear: Conversations Over Music, Ornette spoke in strikingly similar terms. He said, “Do you think ‘the brain’ is a good title for the brain? Well whatever you think your brain is, is that all there is? I doubt it.” In another interview he said, “Is life different than if the title wasn’t called that?” All this also happens to be a crucially important concept in terms of how Ornette wrote music and wanted that music performed: performers were meant to “transpose” the notes by their own discretion. He talked about this transposition constantly in interviews.

It also bears mentioning here that Buckminster Fuller and Ornette Coleman are arguably two of the most famous autodidacts of the Twentieth Century — meaning they learned through self-directed education rather than through institutions or a master-apprentice type situation. Fuller went so far as to refer to himself as “Guinea Pig B”. The two even used similarly offbeat language and crafted their own esoteric lexicons of terminology. For instance, Fuller used portmanteau terms like “Dymaxion” (derived from the words dynamic, maximum, and tension) just as Ornette used the term “Harmolodic” (derived from the words harmonic and melodic…or perhaps also rhythmic).

Prime Design / Time Design follows a somewhat similar approach to The Music of Ornette Coleman, particularly “Forms and Sounds” and “Saints and Soldiers,” and also “Dedication to Poets and Writers” from Town Hall, 1962. That is to say this resembles the music of the serialists of the Second Viennese School (Schönberg, Webern, Berg). Of course, in addition to that Ornette’s son Denardo plays free jazz drums, more like with Skies of America, or, perhaps, even Schnittke‘s Concerto Grosso No. 2 bears some resemblances. Ornette composed the music, but does not perform on the recording. Aside from Denardo, the other performers are Gregory Gelman (1st violin; later sent to prison for arson), Larissa Blitz (2nd violin), Alex Deych (viola) and Matthew Meister (cello). Meister is American, while the other three string players are Soviet emigrants.

The album was, appropriately, recorded live in 1985 inside the 32-foot tall, neon lighted Fullerian Desert Dome on the rooftop of the Caravan of Dreams club in Fort Worth, Texas. The club was the project of Ed Bass, a billionaire entrepreneur born into oil wealth. It featured a lot of avant-garde artistic endeavors, and was part of an urban renewal venture of sorts, but was an entirely private development intended to be commercially profitable. The club also ran a record label of the same name, and this album appeared on that label. That proved to be something of a handicap, as the independent label had limited distribution and promotion, and, frankly, didn’t last that long or release much. This album has never be reissued — of Ornette’s few albums on the label, only In All Languages has been reissued.

Paul Bley has spoken about how when he attended Julliard in the early 1950s, he was taught a line of thinking prominent among “Third Stream” theoreticians that said jazz was developing along a similar path as Euro-classical music. He said:

“We learned something about the evolution of classical music, which had gone through a parallel sequence of development seventy-five years earlier than jazz. Once you realized that, you could look at the history of this European art music to see what was coming next in jazz. It was easy in 1950 to see that the music was about to become very impressionistic, and so it did. . . . After impressionism, atonality was next. The big mystery wasn’t whether atonal music was coming; it was why it wasn’t already here. European music had been atonal since the twenties — what was taking jazz so long?”

Stopping Time: Paul Bley and the Transformation of Jazz (1999), p. 24.

While it is possible to question the kind of historical determinism present in this view — perhaps along lines similar to Leon Trotsky‘s theory in political economics of uneven and combined development, asking why jazz couldn’t leapfrog development paths in the Euro-classical field — there is nonetheless a certain hindsight accuracy to it, in Ornette’s case at least. And when Bley refers to atonality in Euro-classical music, that is a reference, principally, to the Second Viennese School.

A useful supplement to Bley’s invocation of the Second Viennese School is to look at Theodor Adorno‘s Philosophy of Modern Music. Adorno compared and contrasted the composers Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky. He concluded that Stravinsky “restored” a traditional/conservative perspective in the face of crisis, whereas Schönberg offered a more genuinely progressive and new approach via atonality. Adorno still saw limits in Schönberg’s twelve-tone system. Famously, Adorno was very disparaging of jazz, though many have pointed out that his reference to “jazz” was likely more a kind of popular society music and not the genuine article. It is here that Ornette fits in, as someone who carried the torch for what Schönberg suggested, adding his own novel contributions and his own unique formulations. Schönberg, after all, composed from a systems perspective involving the relationships between notes (i.e., syntax). Ornette, in contrast, tended to emphasize paradigmatic improvisational choices and the independence of performers. Adorno did critique Schönberg for applying universalist rationalism in a way that suppressed the individual, the flip side of which just so happens to be one of Ornette’s unique and lasting contributions to music!

In the album’s sleeve notes, Ornette described Prime Design / Time Design this way:

“This piece is designed for five soloists. At different points in the piece, each musician plays in different time signatures: 2/4, 1/4, 2/3, 4/4, 7/4, 9/4 and 12/4.

“The second violin introduces the theme which is then played by viola, the cello, and the first violin. After completing the theme, each musician plays his part as a solo, performed “ensemble.” Each soloist will end at a different place. Second violin finishes first, then the viola, the cello and lastly the first violin.”

Not mentioned by Ornette is the fact that the ensemble comes together for a final collective statement after all the performers finishes their ensemble-performed solos.

In this piece, it is indeed remarkable how Ornette manages to create some of the same “sourness” of tone that he achieves in his alto saxophone playing through written notation for a string quartet. And yet there is a grim, determined hopefulness to the music. The piece is also curious in how it delegates spheres of latitude to different performers, giving the drums apparent free-range in all aspects, while the string players seem to have extensive time-duration freedom even as they tend to follow certain notated melodic statements. This works well for this piece. Ornette had perhaps learned from his experience with Skies of America etc. that Euro-classical players were not as comfortable with improvisation as jazz musicians. It also helps that he rehearsed with the string quartet for a full month leading up to the performance on the recording.

I’ve long been an admirer of Fuller, Coleman, Korzybski, Schönberg, and pretty much all the other names mentioned above. Prime Design / Time Design doesn’t strike me as particularly evocative of Buckminster Fuller. In other words, this isn’t the sort of music that enters my mind when I think about Fuller — I’m more inclined to think of something like “Focus on Sanity” from The Shape of Jazz to Come or the “Buckminster Fuller” song on the Reunion 1990 bootleg. And yet, Fuller and Ornette were most definitely two people of similar minds. Both were futurists, trying to construct a different and better world, be that through music, architecture or whatever, and both being profoundly optimistic about other people having the capacity to similarly contribute in their own ways. In that more general sense, Prime Design / Time Design is a very worthy effort. Granted, this album is much derided. But I find that it holds up admirably, and even more favorably than some Second Viennese School works/performances (e.g., Neue Wiener Schule: Die Streichquartette). I think listeners are mostly likely to enjoy this if they take Ornette’s repeated assertions that his “Harmolodics” theory was applicable to any art form, not just jazz theory, and understand that as an assertion of how he developed musical techniques reflective of certain political philosophies attuned toward freedom principles. Looked at as jazz music, this is going to seem incomprehensible and just plain difficult. Looked at as Euro-classical music, this might seem dilettantish and muddled. But a key point of General Semantics is that there are many ways to look at things and dualistic extremes are rarely helpful. I like to see this as being in service of an agenda completely independent of genre categories like jazz/classical, though I also must admit to thinking this expands and improves upon formulations earlier identified by the Second Viennese School, overcoming some of the limits of their solutions to underlying challenges of musical theory and practice in a way that draws from blues/R&B and — especially — jazz.