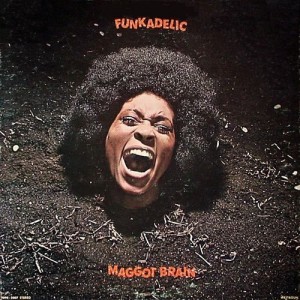

Funkadelic – Maggot Brain Westbound WB 2007 (1971)

Maggot Brain is Funkadelic’s most brilliantly executed album. It is a grab bag of styles, each skillfully employed for the desired effect. There is psychedelic balladry (“Maggot Brain”), trippy soul (“Hit It And Quit It”), folky gospel (“Can You Get To That”), dark blues-rock (“You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks”), heavy metal (“Super Stupid”), zany pop (“Back In Our Minds”), and sound collage (“Wars of Armageddon”). Eclectic to say the least, Maggot Brain is one of rock’s most durable recordings.

When Maggot Brain came out, “Funkadelic” and “Parliament” were conceptually different. Both were the brainchildren of George Clinton, and the exact same group of musicians played in both. The two heads of the beast seemed to each have a mind of their own. “Funkadelic” was the rock band while “Parliament” was the funk band. Over time the distinction lost all meaning (the names actually used gets quite confusing), especially after Bootsy Collins later joined.

This is an Eddie Hazel album. Even on great P-Funk albums, the glue sometimes came apart. Though “Wars of Armageddon” tests the limits, Maggot Brain stays together. George Clinton was the ringleader, but Hazel is the “glue” that sticks here. The title track features one of the great psychedelic rock solos of the Vietnam war era. Hazel’s aching and languishing feeling on that song is diametrically opposed to Jimi Hendrix‘s fiery style, though in general Hendrix comparisons are in order.

The drumming from Ramon “Tiki” Fulwood is another highlight. While forceful and snappy, his drumming is simple. However, the percussion is ingrained in the music, right in step with the solos from Hazel and the amazing keyboardist Bernie Worrell. The echo effects on “You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks” bring back a trick from old sides by blues shouters like Big Maybelle. The rough feel gives give this record’s constant inventiveness some firm roots.

“Can You Get to That” returns to the very ancient concepts of love and equality. This crew believes in those things even if they aren’t commonly witnessed. Funkadelic handles this song is such a way that these ideals never seem futile.

Maggot Brain has empowerment on Funkadelic’s agenda. It’s not happy Sixties soul. The record points out some of the biggest mistakes society has brought upon itself. Yet, Funkadelic seem immune. They have the inside track laid out inside their social commentary, and are willing to share it.