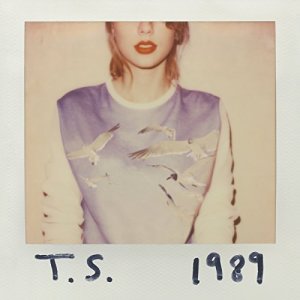

Taylor Swift – 1989 Big Machine Records BMRBD0500A (2014)

A political theorist famously declared the “end of history” in the year the Berlin Wall fell. Even decades on that argument has marked out a very particular debate. Is the political left dead and finally defeated? Anyway, what the hell does this have to do with a pop music album by Taylor Swift? Well, Swift, once associated with pop country music, has made an album firmly committed to revitalizing synthesizer-driven pop, and has named it 1989, the very year that the Berlin Wall fell and when history supposedly ended. It is also an album set up to carefully avoid confronting moral issues.

1989, the album, is a weird proof that history isn’t over. The entire album is very good pop music. Let’s be perfectly clear. This is excellently crafted work, demonstrating vast command of pop music history in the songwriting and delivering impeccable performances. This is a smash hit album, and deservedly so. But let us look beneath that, because it is also an album that essentially tries to re-argue that history has ended. Since the 2007-08 financial crash, which became a pretext for “austerity” policies that divert wealth from the poor and middle classes to the extremely wealthy, and financial speculation as a diversion from the “real” economy has reached unprecedented heights. Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote that the album’s opener, “Welcome to New York,” is “an anthem for carpetbaggers reaping the spoils of rampant gentrification . . . .” He characterizes the entire album as “a sparkling soundtrack to an aspirational lifestyle.” 1989 was still part of what was called the “me generation” after all. By re-producing the simple pleasures of 1980s synth pop, and only offering any emotional attachments of the lyrics as something extra beyond that, this kind of posits that pop music did peak around 1989, and everything since then just spins in circles at the cul-de-sac that is the end of (musical) history.

Really, the sustaining fantasy behind 1989 comes from deeply reactionary politics. Most of the songs speak to the idea that a person can freely drop in to the competitive milieu of the “big city” (from, presumably, “flyover country”), grab some success there, in the form of more fun and “happiness”, then check out. There is a pervasive sentiment that a person can somehow avoid any real risk of such competitiveness, that you always have the possibility to drop out of the city life and secure your place where you were to begin with. It is the idea that you can get all the benefits of this, and the problems one faces, well, they aren’t major problems and can easily be shrugged off by resuming your place where you started. In other words, there is no risk of abject failure by sinking lower than where you started, and the people who succeed never do so at anyone else’s expense. All of this suggests that people have more meaningful freedom than they do in the real world, and it completely trivializes the risks and social costs presupposed by the structural frame of reference that this relies upon. After all, the songs here that gravitate toward the notion of “more bling and better hedonism” assume there is a kind of social treadmill that a person can just hop on, as if that treadmill goes only in one direction, it was always there and always will be, it is available to anyone who chooses to step onto it, and it is never already occupied by someone else.

The self-obsessed, hyper-individualistic attitude of Swift’s album is a rather arrogant testament to accepting change only to the extent it preserves and recreates the basic system upon which it relies, and then only to advance the protagonist’s position within that established frame. This is a Hobbesian world in which life is nasty, brutish and short, but in the meantime people can at least grab some cash and related accoutrements. The people at the top of this grim battleground are, of course, better than those who sink to the bottom — so we are to assume.

Think this is too pessimistic a view of Swift? Well, she did write an op-ed in the conservative newspaper Wall Street Journal. It is laced with all the usual reactionary tropes about the rarity of the good, the prevalence meritocracy, inferences that privatization is necessarily the best social order, suggestions that we should not accept envy as an inevitable consequence of inequality but as something dangerously deviant, cynically commenting that there are no path-dependencies that might hinder a nearly absolute personal choice to succeed or not, and, of course, no recognition of the institutional structures that reinforce the uneven playing field and tilt it in favor of some but not others. The fact that Swift promoted her album with a Wall Street Journal piece is strong evidence of where her sympathies lie, and more generally, that there is an element of class warfare subsumed in it. Swift merely aligns herself with the overlords, like a collaborationist.

So, this album is not so bad, but what it does is celebrate the worst things about the Western world: the long con that a brutally unequal world is inevitable, so we shouldn’t even notice the foundations of a system constructed to be unfair. Why did I say this was a well-crafted album deserving of success? Because it is as pure an expression of the banality of evil as you might find today.