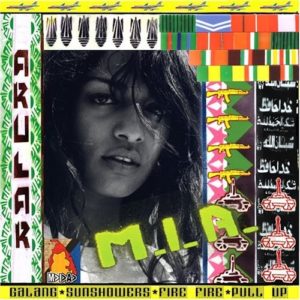

M.I.A. – Arular XL 05667 (2005)

M.I.A. (Missing In Action) makes damn good dance music. It’s the kind that could just as easily bounce off the walls of a club in Great Britain, Sri Lanka, or the U.S.A. Over rumbling, twitching bass, singer Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam ekes out her raps/vocals in short and choppy rhythms. But the real stars here are the producers. Huge drumbeats, sounding thicker than usual, and electronic bleeps blast through “Fire Fire.” The steel drums of “Bingo” create a startling and infectious mash up with synthesized sounds that approximate grating a power saw along a steel washboard. The sound is infectious without being fancy. If anything, the music borders on the jaggedly raw. These songs can, at any moment, sound like any folk music on the planet: dancehall ragga, seemingly ancient Southern bass hip-hop, or pretentious British IDM (so-called “intelligent dance music”). Throwing in IDM influences on cuts like “Galang” is just another way of expanding M.I.A.’s folk music influences. After all, IDM is folk music, just the kind that usually comes from middle class white kids.

Yeah, the lyrics are about terrorism, guns, governments, resistance, boys. But that was Earth(2005) — and also Earthy(2016). Honestly, these are ordinary topics. No big deal if you are alive and aware in the world today. Then again, Maya Arulpragasam is a refugee of the Sri Lankan civil war, and these words do reflect what she knows. The personal element is there, in the lyrics, but the album is more than that. This is ass-shakin’, fist-pumpin’ music. If you’re not moving — literally or figuratively — listening to this, something is broken but it isn’t anything on Arular.

“Galang” is one song not to miss. It’s a tract against pushers, authoritarians and jackasses everywhere. And it’s a practical tribute to that great unchampioned cause of worldwise, worldwide dancing togetherness. At least, man, you gotta get into the moment and just go with this music. Inside the beats, everything moves together. If only this philosophy could translate outside dancefloors, that would be something. It’s also an accomplishment to make it happen anywhere.

With all the artists who have hopped on retro electronic dance beats, it is refreshing to listen to Arular and find it hold up so well a decade later. This ruthlessly and unsentimentally plunders the past and puts those spoils and castoff debris to good and better use for a left/progressive political stance. There is a hint of kitsch, but this is at the same time beyond kitsch. Rarely do such approaches pull off the aggression and in-your-face attitude of Arular though. Little of what M.I.A. did later had the unsettling power of this album — though Matangi eight years later was a return to form (if somewhat of a commercial disappointment).