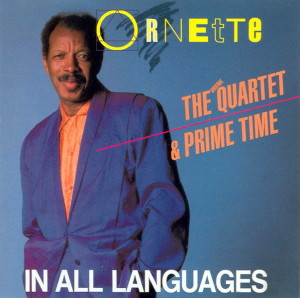

Ornette: The Original Quartet & Prime Time – In All Languages Caravan of Dreams Productions CDP85008 (1987)

The landmark contribution Ornette Coleman made to jazz was in disengaging improvisation from a verse/chorus format built around repeating harmonic structures, and turning it into something that seems to continuously move forward, as Paul Bley explained in a September 2007 interview with Andy Hamilton in The Wire magazine. Bley said,

“There was an article in Down Beat in something like 1954, in which I mentioned that jazz had reached a crisis and that AABA form had too many As, and not enough CDEFG. So I began working with groups where we would play totally free, and that led to a kind of dead end, because ‘totally free’ didn’t necessarily allow you to continue. A totally free piece is a totally free piece, end of concert. *** [But Ornette] suggested ABCDEFGHIJK, in which repetition was anathema *** It wasn’t totally free because totally free was A forever, metamorphosing. It was a form that took hold, because you could finally return to the written music, and the audience had something to hold on to.”

It’s a style more linked with serialism in Euro-classical music (think the Second Viennese School and Anton Webern) than dixieland, swing, bop, or any other movements within jazz or blues. It also echoes Jacques Attali‘s notion of “composing” as a historical phase in the development of the political economny of music that breaks from “repetition”. Ornette told interviewer Howard Mandel (The Wire, June 1987),

“I always tell everybody I’m a composer who performs.”

Coleman wrote in Bomb magazine (Summer 1996):

“The composed concept of the music I write and play is called Harmolodics. The packaged definition is a theoretical method not exclusively applied to music. Harmolodics is a noun that can be applied for the use of participating in any form of information equally without erasing or altering the information. In music, the melody is not the lead. The lead is a sequenced unison form which requires anyone to transpose all melodies note for note to their instrument.”

The term “harmolodics” has caused much consternation, because Ornette has never fully defined it — though he has long claimed to be working on a book (yet unpublished) that will explain the theory in detail. Some aver that “harmolodics” is a made-up term that has no meaning in music theory; it’s just a term Ornette arbitrarily uses to describe his music after the fact. This view tends to find support in the many vague descriptions Coleman has given over the years, like one to John Szwed (The Village Voice, July 22, 1997), where Coleman stated that “harmolodics allow[s] a person to use a multiplicity of elements to express more than one dimension at one time,” adding that “harmolodics means the loss of a style in music.” Yet in an interview he gave Andy Hamilton (The Wire, July 2005) Ornette stated:

“The sound of the piano is not the note of the piano. The note of the saxophone is different to the sound of the saxophone. The note you hear is not the sound of the instrument. It’s the idea of the notes that you hear being applied to the instrument. To this very day, I’ve been working on a concept called harmolodics, which means that the four basic notes of Western culture are all the same sound on four different instruments [per Hamilton, these are “typified by clarinet (Bb); flute, oboe and all stringed instruments (C); alto sax (Eb); and French horn (F)”]. I call that harmolodics. So when I found that out, I started analyzing what people call melody for ideas. But melody and ideas are not confined to any instrument . . . , you don’t have to transpose ideas. *** Harmolodics is where all ideas — all relationships and harmony — are equally in unison.”

Hamilton summarizes this approach in music, which is expressed by Coleman in his later years in the context of transposition and non-hierarchical inter-performer dynamics, as an “extreme sensitivity to nuances of timbre . . . ” and where “the quality of a musical interval is more important than the relation of the interval to any possible key centre . . . .” In short, that could be described as merely the rejection of pre-determined temperament, which has been accomplished long before Coleman arrived. But Hamilton’s rather technical interpretation still doesn’t positively and objectively define the boundaries of what Coleman actually does with his music, at least not in a way that allows other to make “Harmolodic” music without reference to a Coleman recording or performance. It merely points out some things the music is not. The jury may still be out on what Harmolodics really means, and it is even possible that the strength of Harmolodics is that it can’t be explained, but suffice it to say that Ornette Coleman consistently uses the term to describe his musical outlook — one he has developed to shake off the arbitrary confines of 20th Century Western musical forms and notation.

In a June 1997 interview with Jacques Derrida, Coleman explained his goals in music:

“I’m trying to express a concept according to which you can translate one thing into another. I think that sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don’t need the alphabet to understand music.”

This is important in suggesting that Coleman’s Harmolodics may be as much a political statement that is applied to music as any sort of concrete artistic practice. He continued,

“In fact, the music that I’ve been writing for thirty years and that I call Harmolodics is like we’re manufacturing our own words, with a precise idea of what we want those words to mean to people.”

Coleman then questions his interviewer,

“Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts? Can a language of origin influence your thoughts?”

(“The Other’s Language: Jacques Derrida Interviews Ornette Coleman, 23 June 1997,” Les Inrockuptibles No. 115, August 20 – September 2, 1997, Timothy S. Murphy trans, Genre, No. 36, 2004). That quote is basically a restatement of the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis of linguistic relativity. This also ties in to something sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has written about with respect to autodidacts (people who teach themselves things), who are typically shunned and rejected by people trained in “legitimate” modes of discourse that are associated with dominant groups and institutions. This is because autodidactism is commonly (implicitly) perceived as a threat to those dominant groups and institutions — threatening their ability to reproduce themselves and regulate the status of members of those groups. John Litweiler‘s bio Ornette Coleman a Harmolodic Life (1992) recounts stories of Ornette feeling ill when he realized how much his own methods differed from accepted norms when studying with Gunther Schuller and of the numerous physical beatings Ornette suffered at the hands of those threatened by his new techniques when starting out as a musician.

Harmolodics may, possibly, be explained in terms of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan‘s theories regarding three orders of The Real, The Imaginary and The Symbolic, inasmuch as Ornette attempted to avoid the burdens of conformist and limiting social norms through a passion for The Real. The Real in this instance is the elusive core of the ideas, thoughts, feelings, etc. that is the subject that the musical discourse is about, ultimately a lack constituted by those ideas, thoughts, feelings. The Symbolic is the musical expression as such, the written or performed notes and sounds. The Imaginary is the ideology — Harmolodics — that mediates between The Real and The Symbolic, a kind of fantasy or dream that subjectivizes material experience. In this formulation, Harmolodics may be something of an attempt to break free of socially-imposed limits on the structuring of human thought by pre-existing musical notation and structures in the Symbolic order (what Lacan called “the Big Other”, a sort of colonization of thought that creates but also limits the scope of desire), and find more space that overcomes a lack of free, diverse and unique expression, through new fantasies (Imaginary constructs) that facilitate a connection between the symbolic musical notes and sounds (which create a desire to express something through them) and a kind of unattainably direct reality, what he various refers to as “thoughts” or “ideas” or “emotions”. Harmolodics would therefore be a kind of myth of freedom. It was radical because it challenged the idea that the existing system of Western music created a justified order, or provided freedom already. Ornette never completely breaks from the socially constructed symbols of musical form. He is still trying to express something through musical sound, just like the pre-existing musical order professes to do. He did try, however, to use music to express something real outside musical symbolism, and yet impossible to express directly. In this way, Harmolodics might be seen as evincing a super-Platonic “notion that empirical reality can ‘participate’ in an eternal Idea, that an eternal Idea can shine through” the spatio-temporal reality and appear in it, while recognizing that “the distinction between appearance and essence has to be inscribed into appearance itself.” (to quote Slavoj Žižek, Less Than Nothing 2012). So, in some sense, Harmolodics allows Ornette to revisit all sorts of common topics with a fresh perspective, or, as the case may be, from multiple perspectives. A kind of constellation of symbolic representations can thereby imply the inexpressible ideas or feelings that emerge at the breakdown of those musical symbolizations. This may be why the apparently contradictory nature of Ornette’s Harmolodics is actually its greatest strength. For Ornette, the dream (Harmolodics) embedded in his new musical forms was a means to inscribe ideas, thoughts and emotions with more democratic, egalitarian, and, self-determined contingencies into music. In this way Harmolodics gives the appearance of being just another musical theory, just another purely technical program for putting together sounds in a “musical” way, which masks the political objectives bound up in it. Going back to Paul Bley’s characterization, about making repetition anathema, this is the way a black man who lived through Jim Crow America could envision expression in a different sort of society, a free one, by imagining the possibility of change and reconstructing musical forms to suit those possibilities. This was a rejection of those symbolic limitations of musical forms or styles that deny change, rather than a perpetuation of the inherent stasis of something like European contrapuntal music (a symbolic order), for instance, or even the tonal centers of be-bop jazz or the formalized rhythm of swing jazz. These ambitions or dreams are not immediately realized through music, but they make it possible to conceptualize a movement in that direction. All this pushes toward fulfilling the lack of freedom and free expression. What Bley describes as “totally free” is usually anything but that, and instead music that falls back on disavowed or unacknowledged mental hangups and limitations. Ornette jumps right past that problem by putting forward Harmolodics as a guiding principle that both establishes a set of rules and laws for musical performance and at the same time suggests transgressing those very rules and laws. There is an endless back-and-forth baked into Harmolodics in this way.

At its best, Ornette’s music addresses a lack of freedom in a way that does not simply revel in a completely anarchic morass that pretends to be the complete fulfillment of freedom, as if all limits on freedom are simply instantaneously shed and overcome. Instead it makes constant recourse to melody, syncopation, and other compositional details that provide a kind of guidance, fractured by techniques that in fact often go beyond socially accepted stylistic forms, complete with squawks, conflicting solos, and irregular beats. This might be what Ornette means when he talks about the melody not being the lead, because in the ideology of Harmolodics the melody is just a symbolization, a kind of secondary aspect tied to mere technique, and not the “note” or the idea that is what is inscribed into the music through melody, and other techniques like harmony, etc. In its most utopian aspect, the tension between out of reach democratic egalitarianism and the limitations of socially accepted music forms in a racist, restrictive society is mediated by the dream of passing boundaries and evolving in a way that does not simply reproduce the existing music forms, and by extension, the limited kinds of ideas, thoughts and feelings they tend to engender. Freedom, in this conception, is therefore not a state, a condition that finally overcomes constraints preventing its realization, but rather a process, already graspable, that can never be fully resolved. The only thing to do is patient, simple work along these lines.

In Goethe‘s Faust, a professor makes a wager with Mephistopheles that he can live without christian morality and not regret it. As Faust is dying and poised to lose the wager, he wishes he could live to keep trying. At that point angels come to save him, saying, “He who strives and ever strives, him we can redeem.” (Goethe, Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy). Ornette’s wager is that he can live without European musical forms and symbolization, and the narrow range of thought and emotion they embody, and not regret it. He can’t fully succeed. Like Bley said, Ornette’s music is not totally free. But he strives and ever strives. And above all, he strives to eliminate the mental hangups that that suggest limits on musical practice that were never there. This is what made Ornette among the most important figures in modern jazz. But there is the caveat that his Harmolodics is a kind of empty theory, that doesn’t have any particular subject. The democratic ends he tries to express in his compositions are just one possibility, and in a society that is already free his music could be used to move toward oppression. Well, it could also end up wallowing in nothing more than entirely circular quagmires of supposedly self-evident emotional truths, even if no more than empty narcissistic, hedonistic, self-indulgent platitudes. In other words, it could end up reverting to the endless metamorphosing that Paul Bley described, albeit shifted to endlessly cycle over egotistical personal experience.

The album In All Languages was a double LP, with one disc featuring Prime Time and the other Ornette’s reunited 1960s Quartet. Many of the same songs were recorded with both groups, including probably the most notable new song “Latin Genetics.” Listening to both versions allows comparison and contrast, particularly with respect to the different rhythmic textures and phrasings. It would be hard to call this one of Ornette’s best album-length efforts. The sterility of the recording sounds oppressively dated just a few decades out. But the in making an effort to tie together the “classic” style of his 60s Quartet with the very different approach of Prime Time in one work, it highlights how Ornette’s early work looked forward towards something that was just beginning — a something slightly vague and unspecified — while Prime Time was something of a declaration of victory — perhaps a bit premature — that the democratic future of music had been achieved.