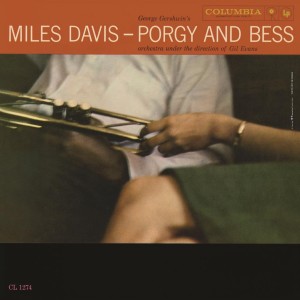

Miles Davis – Porgy and Bess Columbia CL 1274 (1959)

Bold and uncategorizable, outside the scope of translation, George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is a visionary’s upheaval of the rule of the mundane and stagnant. Any cursory look to American music must include it. Miles Davis and Gil Evans’ rendition is among the most enduring. For use as a film treatment’s soundtrack, Miles collaborated here with his alter ego Evans who conducts the orchestra, handles all arrangements, and contributes a song of his own. There are volumes written on Gershwin’s masterwork and this rendition (because this is an instrumental rendition, excluding all singing, it is fair to exclude Ira Gershwin and DuBose Heyward’s contributions to Porgy and Bess), but no outpouring of words captures the impulsiveness of the performance.

Many believe that 20th Century composition began shackled by Euro-classical conventions. The important things had already been done, leaving little of interest. The odds of success were certainly slimmer than before. This prompted many to follow the lead of Arnold Schönberg or those developing various just intonation and conceptual systems of music. However, George Gershwin–and subsequently others like Eric Dolphy–shows that it never had to be strictly about systems and rules but could be about divining the poetry of exceptional circumstance. If the vision fit in simple forms, so be it. Porgy and Bess conveys the common things of life in a most uncommon way.

Gershwin was a wild card among American composers. His firm belief in the value folk music opened untold avenues. He stirred up wonderful human traditions in colorful sounds. Steve Reich has said, “the human construct we call music is merely a convention–something we’ve all evolved together, and which rests on no final or ultimate laws. And it sails, in my mind, like a ship of light down an endlessly dark corridor, preserving itself as long as it can.” (“Steve Reich In Conversation with Jonathan Scott,” New York City 1985; from the liner notes to The Desert Music). Reich’s own views on music make plain Gershwin’s insight, even though, on the surface, Gershwin doesn’t appear particularly serious. He was popular after all. Well, Erik Satie wrote cabaret songs–great ones. Gershwin may not have fashioned his own language, but he found, as expressed in the heart of his works, unspoken beauties. His respect and humanity shine through every note. Academics are simply irrelevant.

As for the Miles/Evans recording, it is a success on every level. Miles plays a little trumpet and a little flugelhorn. His Harmon mute often appears to lend biting sincerity to his solos. His touch is soft and remarkably smooth. A particularly memorable rendition of “Summertime” is a favorite with Miles’ dry, swaggering sense of rhythm.

The centerpiece truly is “Prayer (Oh Doctor Jesus)”. Gershwin, Evans, Miles and the orchestra all communicate as one. Miles’ horn raises a soaring angelic voice above the churning rumble swelling about him. Pleading and sincere, Miles plays his brightest. At the dénouement, he draws back into a husky state of exhaustion.

After such a vigorous song, the challenge to follow it is immense. Gershwin builds slowly with “Fishermen, Strawberry and Devil Crab.” The subtleties in the flow of Porgy and Bess seem effortless.

Miles later recalled (in his autobiography Miles) the two of the most challenging songs he had played were “I Loves You, Porgy” here, and “KoKo” back with Charlie Parker (reputedly, Dizzy Gillespie took over on trumpet for at least part of that recording). “I Loves You Porgy” makes a touching expansion of the emotional range of the record.

Evans manages to maintain the intimacy of a small combo with the larger orchestra. He uses tubas, flutes, French horns, and clarinets to their full potential in the orchestra. Some of what Evans does is not so fluid though. The inclusion of an Evans original, “Gone,” is nothing short of shocking. Not to say it’s a bad tune, but its inclusion is a significant change–much more so than doing an instrumental rendition of an opera. The Gershwin score certainly isn’t rigid. At the outset the results are indeterminate. But placing “Gone” in the middle breaks up the flow of Porgy and Bess even in a non-vocal version. Still, this record is a wonderful meeting of talents to deliver a common vision.

Don’t call this jazz, opera, folk, pop or classical. Don’t call it anything. Just listen and let it melt boundaries.