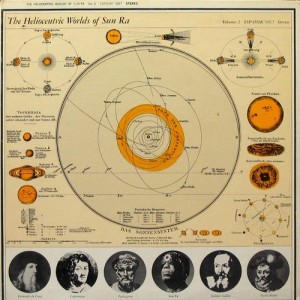

Sun Ra and His Solar Arkestra – The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra, Vol. 2 ESP-Disk ESP 1017 (1966)

The best of the Heliocentric Wolds Sun Ra albums. This album may be conclusive proof that the “genre” of “Free Improvisation” (which, incidentally, does not exist) is simply a racist and wrongheaded attempt at revisionist history, nothing more than a power play to shift interest and attention from African-American musical innovators to white hangers-on while simultaneously attempting to create false credibility in the cheap knock-off stuff. The magazine The Wire had a “free improv” section and readers would regularly write in suggesting that the term be abandoned as not being distinct from “jazz”. In response, the magazine’s editor has noted the term’s “political” connotations. Pay attention: why is it that advocates of “free improv” are ALWAYS white (and also generally white males)? And why is it that the strongest musician advocates of “free improv” arrive with no credentials in the jazz realm? And why did one of the originators of “free improv”, Trevor Watts, in essence repudiate the concept? And why don’t practitioners of “free improv” that meld Euro-classical and jazz forms and techniques simply use the term “Third Stream”, which already existed? And why did the term “free improv” originate at the same time “British Invasion” rock groups were taking songwriting credit for blues songs actually written by African Americans? And why do advocates of the term meaning something outside of “free jazz” tend to always have a vested interest in differentiating themselves from practitioners of “free jazz”? There are answers to ALL of these questions.