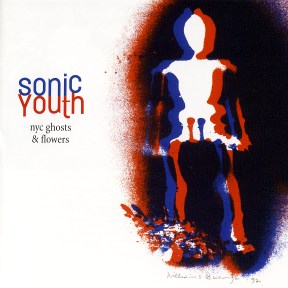

Sonic Youth – NYC Ghosts & Flowers Geffen 069490650-2 (2000)

NYC Ghosts & Flowers caters to a very specific audience as it began a planned trilogy in tribute to New York City and all it represents. Opinions differ greatly on the album’s merits — to some this is the band’s single worst album, to others this is a return to underground authenticity. Though this remains one of my favorites. There are a few slow moments and it’s certainly not a watershed Sister or Daydream Nation, but this is the Sonic Youth at their most experimental. It isn’t experimentation for its own sake either. The inventive spirit overpowers the nostalgia (and the name-checking references to the past). Maybe I’m a sucker for underground culture. But anything that so insightfully captures shadings of people like William S. Burroughs (the album cover is an image he created), Hubert Selby Jr. and Jean-Michel Basquiat and of the ongoing revolution of the universal consciousness is okay by me. This album is kind of like a research project, going back to explore the pre-history of the punk movement that is typically associated with Sonic Youth and its fan base and exploring how that legacy is still relevant. That especially means looking to the 1950s Beat Generation bohemianism and the 1960s hippie/Yippie counterculture, but also perhaps the free jazz and experimental music scenes of those eras. The lyrics are as good here as anything Sonic Youth had conjured up before. The sneering snottiness is held in check and instead they present thoughtful long-form concepts, adapting the vocal mannerism of the past to reference a kind of evolution of different modes of artistic discourse. The song structures are also more open-ended, and they find ways to transition between spoken monologues, white noise set pieces, guitar riffs, and guitar solos that seemed lacking though much of their mid/late 90s albums. I suspect that Sonic Youth looking back before the 1970s put off many listeners, who only wanted the band to have loud, crunchy guitar solos appear with predictable regularity — there isn’t much of that here. That, and there are markedly different rhythms in play here, which are frequently static and cerebral while being insistent and present as a force equal to or great than the vocals, melodies or noise effects. But in displacing of all the familiar devices with new techniques, the band (and co-producer Jim O’Rourke) deliver a recording that is as refined and well-recorded as anything they ever released, even as it revels in dissonance and artistic devices that alienate the audience to make certain points (usually by transitioning from or contrasting with the aspects with a distancing effect). If you don’t want a rock album to challenge you, then of course you won’t like this album. If you do, however, you might get something out of this one.