John Coltrane – Interstellar Space ABC Impulse ASD-9277 (1974)

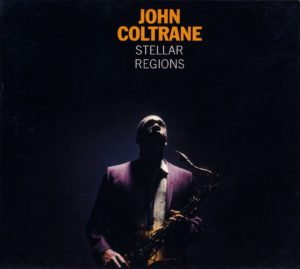

Coltrane’s Interstellar Space is like a soundtrack to Arthur Rimbaud’s Une Saison En Enfer [A Season in Hell], as Stellar Regions is for Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations [The Illuminations]. This is one of the more challenging Coltrane albums. It demands constant attention. But it is rewarding. Coltrane had added some of the layered approach of his wife Alice into his sound. His fiery forays here are as dazzling as they are ingenious. His passion perfectly matches his virtuosity.

Rashied Ali plays some remarkable non-linear rhythms on drums. Though he keeps time in a sense, it is a subjective time with no predetermined time signature. The music is of the moment, in the sense of having no need of time to progress. It is confusing, but the instantaneous possibility of the moment is supreme and Ali’s rhythms are presented as they are naturally. Instead of conforming to any external formula, Interstellar Space is spontaneously (and thereby simultaneously) composed, lived, and performed.

This is a remarkable effort in musical abstract expressionism. While totally true to the impulsiveness of free improvisation, this is also a strong statement of Coltrane’s (and Ali’s) struggle to resolve the inner self and the outer one in the most idealistic sense of reconciling a personal place in a harmonious social context. Whew, it is that and more. This is one of the great efforts to be a completely free individual in a world as great as imaginable.

Interstellar Space rebels against order and structure, in a sense, but only against falsehood. One of the basic contradictions of so-called “free jazz” was stated quite succinctly by pianist Paul Bley, talking to The Wire magazine in 2007 about the saxophonist Ornette Coleman:

“There was an article in Down Beat in something like 1954, in which I mentioned that jazz had reached a crisis and that AABA form had too many As, and not enough CDEFG. So I began working with groups where we would play totally free, and that led to a kind of dead end, because ‘totally free’ didn’t necessarily allow you to continue. A totally free piece is a totally free piece, end of concert. *** [But Ornette] suggested ABCDEFGHIJK, in which repetition was anathema *** It wasn’t totally free because totally free was A forever, metamorphosing. It was a form that took hold, because you could finally return to the written music, and the audience had something to hold on to.”

What might be added is the sort of complaint that the feminist Jo Freeman made about (so-called) structureless groups, which tend to have a de facto structure (tyranny) if there is no formal structure. These things are basically what Coltrane was working through on his own with recordings like those on Interstellar Space. The music wasn’t just a formless morass, metamorphosing, but neither was it music that was composed in advance according to a detailed score. It fell somewhere in the middle, loosely organized without that loose organization seeming like a constraint, able to go wherever and equally the product of the efforts of both Coltrane and Ali. The performers aren’t operating completely independent of one another, in some kind of purely horizontal relationship. But they are constantly negotiating the terms of how the music evolves. One might quote a political economist here:

“But is this anything other than picking up Rousseau’s classic idea that being free, in politics, does not mean living outside of all constraint, but living according to rules we have set for ourselves? That is, living according to verticality [that is, hierarchy,] such as we have chosen to institute it, in the form that we have chosen to give it.”

This is a particularly useful analogy, given that Rousseau favored small states, much as a sax/drums duo is the smallest possible “group”, meaning that the problem of negotiations between participants doesn’t face the problem of exponentially-increasing complexity that shackles larger groups. This isn’t to say that the horizontal vs. vertical question is entirely side-stepped, but rather the question of verticality is addressed in a sort of controlled laboratory setting, if you will. Rashied Ali just makes it deliciously apparent how much space a “sideman” has within the context of a Coltrane group, and by extension, how the role of a “star” soloist can be rethought within the free jazz movement.

Coltrane recorded Interstellar Space on February 22, 1967; he died on July 17, 1967. For a considerable time these were believed to be the last known studio recordings he made, though additional studio recordings were later discovered. “Venus: Second From the Sun; Love” (AKA “Dream Chant”) is, melodically, extremely similar to “Stellar Regions” from Stellar Regions, which was recorded a week before Interstellar Space but not released until 1995. Many of these recordings were unnamed and only later named by Alice Coltrane for release. Though posthumously released in album form, these songs do make up a coherent set of music. They all cohere around a common musical perspective.

While made up of archival recordings, Interstellar Space remains one of the most essential John Coltrane albums. Listeners should seek out a reissue that includes the excellent bonus track “Leo,” which was recorded at the same session as the other songs but left off the original LP due to space constraints (but previously released on The Mastery of John Coltrane, Vol. 3: Jupiter Variation), plus a “Jupiter Variation” false start track.