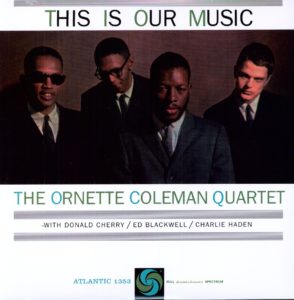

The Ornette Coleman Quartet – This Is Our Music Atlantic 1353 (1961)

The biography of Ornette Coleman in the late 1950s and early 1960s is fascinating. He recorded all his early studio albums in Los Angeles, and This Is Our Music came from his first sessions in New York City in later summer of 1960. A lot had happened since he departed L.A. for good. For one, he had finally, after many years, secured a running stand of gigs performing live (at The Five Spot Cafe) in 1959, and had become a polarizing sensation in the New York jazz world. He followed that with a tour, and then back to more gigs in New York City. What is more, while continuing to work with core collaborators Charlie Haden (bass) and Don Cherry (trumpet), his working band underwent an important shift. Drummer Billy Higgins lost his cabaret card (essential for live performers in New York City at the time), which provided Ornette with the opportunity to reunite with innovative New Orleans drummer Ed Blackwell, who moved the group’s rhythmic structure further away from bebop. Blackwell was an old friend of Ornette’s. Suffice it to say, this version of the Ornette Coleman Quartet was well versed performing together by the time they entered the studio to record what became this album.

In the liner notes to the following year’s Ornette!, Gunther Schuller described the overall structure of an Ornette solo this way:

“Little motives are attacked from every conceivable angle, tried sequentially in numerous ways until they yield a motive springboard for a new and contrasting idea, which will in turn be developed similarly, only to yield another link in the chain of musical thought, and so on until the entire statement is made.”

This almost equates Ornette’s musical approach with the cubism of the likes of Picasso, a style frequently described as when a visual artist depicts a subject from a multitude of viewpoints in a single work.

George Russell also commented in 1960 about his own concept of “pan-tonality” and how Ornette represented a kind of implementation of an overall sound not bound to any one tonal center, whereby, as critic T.E. Martin later added (“The Plastic Muse, Part 2,” Jazz Monthly June 1964), all tonalities are possible.

Ornette and his sidemen have never offered any satisfactory explanation of “Harmolodics,” the musical theory Ornette applies. Ornette tends to describe this as playing in “unison”, but the problem is that he uses that word in a way that is sui generis and therefore non-explanatory. One of the more useful comments they have made (both Ornette and sideman Don Cherry are on record making such comments) is that the players think through all the chord changes in a song and then play something beyond the changes. This comment doesn’t entirely make sense either. Ornette’s bands didn’t exactly play atonally. So this seems to circle back, perhaps, to George Russell’s comments about “pantonality” and Gunther Schuller’s comments about “motives”. The underlying question is what links each sound together, harmonically (when played simultaneously) and melodically (when played over time). Playing “beyond the changes” might mean that the subject of each song is never stated directly, but instead a copious amount of indirect statements (untethered to chord changes) imply what is missing and perhaps cannot be directly expressed by chord changes. But really the reason why Ornette attempts any of this in the first place seems to lie beyond pure musicality and rest somewhere in the realm of sociopolitical ideology; Ornette’s worldview put him squarely on the political left, close to anarcho-syndicalism (don’t know what that is? Read Ursula K. Le Guin‘s classic sci-fi novel The Dispossessed).

This Is Our Music is one of the essential Ornette Coleman albums. It opens with the stupendous “Blues Connotation,” one of the songs that draws from Ornette’s background playing in R&B bands. He does a few low, rumbling growl/squawks close to the R&B sax tradition. The song is a great example of one of Ornette’s most endearing qualities. This is a song with a melody that has an innocent, childlike simplicity, and yet, this is precisely not some sort of retreat to a fantasy of a safe and secure childhood. No, this is about mature adult things, the sort of music that is beyond the capacity of infant children. Yet it is an argument that mature adult topics should include a space for innocence and simplicity and goodness (compare here the physicist character Shevek in Le Guin’s novel mentioned earlier).

“Beauty Is a Rare Thing” is a slower tune that is an early example of Ornette’s interest in orchestral composition. Haden plays his bass arco (bowed) insistently and deliberately to provide subtle and slowly evolving support, and Blackwell plays lightly on his toms (not unlike how a symphony would play tympani) and switches to cymbal rides and washes for a stretch. Cherry plays brief squeaks behind Coleman, quite atonally. The song is nothing if not a piece that builds and develops a sense of momentum in spite of the angular and abrupt soloing that would normally seem to lead in the opposite direction.

“Kaleidoscope” is a twisting, complex composition. It is a fast number drawing from bebop. It quickens the tempo to something allegro (fast) after the largo (slow) “Beauty Is a Rare Thing.” It’s also a chance to hear the players stretch out with showier solos. Blackwell is all over his kit. The horn players have been described as playing violently (relatively speaking).

“Embraceable You” is a rare standard (rare for Coleman albums that is). It gets an appropriately sarcastic reading, complete with the horn players offering swaying, almost staggering lines, at times like a band playing gag lines to get a rise from the audience.

The rest of the album continues at a high level, mostly reaffirming what had already been mapped out earlier on the album. But the compositions are strong, especially the quirky charm of the lyrical “Humpty Dumpty.”

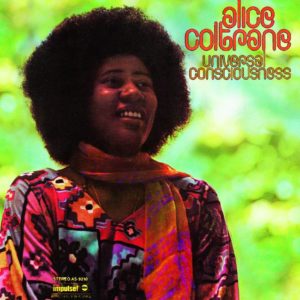

This Is Our Music stands as one of the finest Ornette Coleman albums from top to bottom. Even the cool indifferent photo of the group on the album cover, carrying the humbly provocative title “This Is Our Music,” has become iconic (and frequently tributed on other album covers).