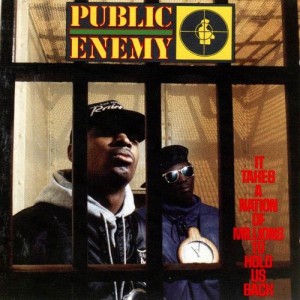

Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back Def Jam BFW 44303 (1988)

No one could have expected It Takes A Nation of Millions. It was too much of an album to expect. Chuck D packs thought provoking messages into a bomb he detonates before you. It Takes A Nation of Millions wakes listeners to a whole new level of consciousness.

Flavor Flav was out there. Complete with clock (though Chuck D still wore one too), he was the wild card that made Public Enemy work. His crazy rhymes kept coming. He injected a different sense of rhythm into the whole. It was an attack from many sides as long as Flavor Flav was there.

Terminator X, Professor Griff and the others tend to be forgotten, as they aren’t even on the album cover. They were critical. Terminator X’s (and Johnny Juice‘s) aggressive scratches and the hard beats of The Bomb Squad were relentless. Looping again and again, the most powerful elements were isolated. The push was overpowering. Public Enemy had a sound that might have been a lot of things, but it certainly could not be ignored. It Takes A Nation of Millions dominates as long as it is playing.

The density of what is on a Public Enemy record had roots, but this was a new kind of concentration. Miles Davis’ On the Corner provided the layered street funk attitude. The harsh beats and fondness for raw noise resembled industrial music too (for instance, Mark Stewart‘s As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade, Ministry). As Michael Denning wrote in Noise Uprising about early sound recordings just before the Great Depression, “If noise is unwanted sound, interference, sound out of place, it is also a powerful human weapon, a violent breaking of the sonic order. *** In this frame, these musics represented the refusal of deference, the assertion of noise for noise’s sake, the singing of the subaltern . . . .” This revolutionary attitude also — even if by chance — echoed punks like The Pop Group. Public Enemy sorted through every possibility to direct their efforts. They created chaos as needed, and could cut through it at will. Chuck D and his crew had control. That was the difference. They weren’t held back by the ordinary expectations of continuing to build on the past. It was more about striking out in the proper direction. Working with exactly the same sounds other musicians used, Public Enemy used them as ammunition to make sure their path was clear.

There is definitely a surplus of ideas here. There is more in a single song here than in many artists’ whole careers. Public Enemy works very hard to put so much across in every song. It helped, perhaps, that the band was so large. There were many talents to draw on.

It is also obligatory to mention that this was a record made before the advent of sample clearing. So no one makes them this way anymore. Not that anyone really did at the time either. When jazz pianist Cecil Taylor got started he did something unique, but it wasn’t long before he ratcheted up the speed and complexity by a factor of ten. It is like that here. Run-D.M.C. and the early hip-hop pioneers were no doubt influences and precedents, but It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back took all that and delivered it at hyperspeed. If that weren’t enough, all the samples come at the listener in a barrage of noise, squawking repetition and booming thuds. The samples draw on history, allusion and implied meaning, but also refuse to simply restate existing meaning, instead insisting on imposing further meaning. Put another way, PE and the Bomb Squad didn’t just appropriate the proven appeal of the material they sampled, but took that as merely a starting point, a contextual reference point, to fashion something of their own that had significance beyond that of the sample.

The band uses the samples in a way that really creates a platform for the political messages. Although the harshness and aggression of the beats seems like a way to frighten listeners, it was also a way to draw in the willing. Like heavy metal? Well, PE threw out some metal samples, but just shards and slivers, enough to make a listener who is into it find some common ground, but only enough to catch her attention and propose a deeper connection. It is the same for the vintage soul and funk samples. They provided some basis for their stance too. There is rapping about not believing the hype, but they also include a snippet of a radio DJ calling them “suckers”. And when building momentum, they play a live recording from a London show. This wasn’t just a bunch of conclusory opinions. This is an album that makes the effort to provide some evidence to contextualize its stances. But what really made this band — and this album in particular — so special was that they built everything from very elemental concepts. Chuck D and the Bomb Squad didn’t just present political programs, they built them up from more fundamental positions. They get into deeper, abstract philosophical questions, and their political stance unfolds from them.

Public Enemy was self-aware of their own controversial status in the music industry. This comes to a head on songs like “Don’t Believe the Hype.” They engage this controversy, without defining themselves entirely by it or dismissing it outright. They don’t get caught up in merely self-referential excess either.

One of the great albums of its day, or any, It Takes A Nation of Millions raised the bar. Public Enemy were an exceedingly intelligent group. It was the minds behind the music that made the album. They still focused all their attention on being levelheaded champions of their people. Fuck the finer points, it’s just good to listen to.