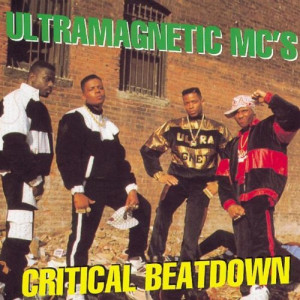

Ultramagnetic MC’s – Critical Beatdown Next Plateau PL-1013 (1988)

The Ultramagnetic MC’s somehow got lost in the shuffle. While a steady following of fans and critics have sung praise since the beginning, they never quite had the album sales they deserved. Not your typical hip-hop album, Critical Beatdown remains an essential album, one of the best debut albums by a group in any genre.

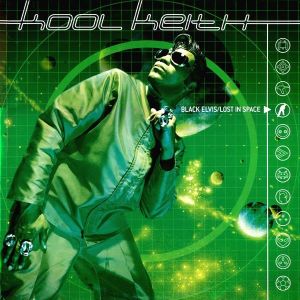

Hip-hop always was underground, but by 1988 there also was stuff above ground too. Some groups like the Ultramagnetic MC’s stayed underground and laid the groundwork for a movement in the 1990s. Their lyrics were smart, and mixed with complex new beats. After fifteen years hip-hop had a whole new vocabulary, made possible largely through new technology like the sampler. The rhymes are faster more intense. Also, the focus is decidedly urban. The lyrics go beyond the simple themes so common a few years earlier. “Travelling [sic] at the Speed of Thought,” “Kool Keith Housing Things,” and “Give the Drummer Some” are showcases for master genius of rap Kool Keith. He comes in with his “usual” style; he delivers a vocal rhythm that no other MC can duplicate or even match. While his lyrics look simple on paper, his delivery flows backwards. The substance and form is different, but Kool Keith has the same command of words as the beat poets. On “Feelin’ It” it’s easy to miss the line: “but I guess I’m white/ while others are wrong.” All Keith’s lyrics are biting and intelligent. He disses everybody. But why not? With a record like this, the Ultramagnetics were the top game around.

The group’s urban flavor is never bleak. The lyrics simply accept circumstances and pump out great tunes. A subtle shift from merely rhyming about lyrical superiority, the Ultramagnetic MC’s turned that tradition sideways. They explained why their rapping superiority mattered. Hip-hop moved to a higher order of complexity. More than just a necessary mode of oral history, new hip-hop chose to go to the farthest reaches of pure technique. An album like Critical Beatdown just gets better over time.

“Critical Beatdown,” “Ease Back” and “Ego Trippin’” feature the combined assault of all the MC’s, trading rhymes at breakneck speeds. They work together, never letting individual talents work against each other.

What set this record apart in its time was use of the sampler. The sound was fresh, and subsequently overused as a gimmick by lesser groups. Critical Beatdown may have been a continuing experiment with new techniques, but it still works today. These guys even mix in a Mark Hamill line from Star Wars (advising to “go in full-throttle”). Such eccentric samples would be fluff in any other hands. The Ultramagnetics flex their rapping muscle just enough to give us a taste — true masters.

This album is a classic, and never received its due. Hopefully, revisionist history will be kind to the Ultramagnetic MC’s who never got the fame they deserved.