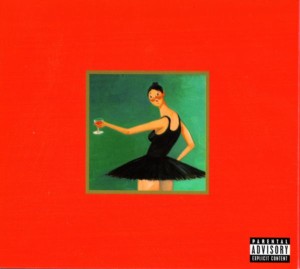

Kanye West – My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy Roc-a-Fella B0014695-02 (2010)

Let’s take the title of Kanye’s album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy at face value. This isn’t the kind of fantasy that involves wizards, leprechauns, fairies and ogres. It references the sort of real-world arena of desires that drive human beings in one direction or another. Psychology tells us that pleasure often comes from transgressing rules and boundaries. So the question then becomes one of what transgressions we desire, and how we engage in those transgressions. This is what makes Kanye’s album so interesting. The song “Runaway” is sort of a centerpiece of the album. Opening with a stark, rhythmic melody played with single notes on a piano, it then bursts out with groovy hip-hop drums and sustained synthesizer chords that imply a forward movement. Then Kanye starts rapping. There is sort of a tipping point here. Look at this from the standpoint of the searing return of morality. The political landscape of 2010 was pretty bleak in the Western world. There was a financial crash and a “jobless” recovery that only benefited a few elites — there are graphs that show the rich cannibalizing the wealth of the poor in this period. But then, people had enough. Just a few weeks after My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was released the Arab Spring happened in Egypt. Is Kanye’s “Runaway” a condemnation of any of this? No. It is a confessional song. He describes womanizing, and conveys that he is a douchebag, an asshole, scumbag, jerkoff. But, but, but, that isn’t all he’s doing. In one of the most memorable choruses of the era, he raps:

“Let’s have a toast for the douchebags,

Let’s have a toast for the assholes,

Let’s have a toast for the scumbags,

Every one of them that I know

Let’s have a toast to the jerkoffs

That’ll never take work off

Baby, I got a plan

Run away fast as you can”

These lowlifes still get a toast. If you agree, as the song invites you to do, this means there must be compassion for even the worst. This is the sort of thing that religions like christianity have been preaching — with varying success — for millennia. It implies a sense of solidarity, that everybody matters, not just the folks who work all the time to “gain wealth, forgetting all but self” as the Lowell Mills Girls used to say at the dawn of the second industrial revolution. This “dark twisted fantasy” is dark and twisted from the sort of view that it is a refusal to obey and accept a “proper” place in society. And yet, at the same time, “Runaway” is a plea from someone else to “run away” as the narrator sort of can’t completely break away. This is really the brilliance of Kanye. Bringing in a race relations component — as is appropriate — he kind of asserts the post-racial concept that a black man has the same right as a person of any privileged race to be a douchebag, asshole, etc., even as he acknowledges how those qualities are evil, in a way. This, really, deserves a toast!

“Power” is another great one. The lyrics “I was drinking earlier, now I’m driving” epitomize the recklessly gradiose vision of what happens across the entire album. One reviewer wrote about Kanye’s style of self-important self-aggrandizing that “It’s like being in a bar stuck in a conversation with a stockbroker who tells you how much money he earns and tells you about his new Porsche and shows you a picture of his wife and kids and then suggests you go on to a Gentleman’s Club that he knows.” Kanye’s use of such an attitude is commentary on the privileges of celebrity status, how it seems to objectively require this kind of self-aggrandizement, and yet the dude is kind of mocking it all at the same time. Kanye is at his best implying these things, hitting them obliquely rather than talking about these issues explicitly. His approach is to cartoonishly debase the role he’s in, drawing unsentimental connections to the structural underpinnings of how somebody becomes a “successful” musical star, and, crucially, refusing to create a separate context for celebrity as something that is beyond the “thug life” that in hip-hop is often portrayed as a way of paying dues in a system that allows its stars to escape that life. Kanye paints them as inseparably part of the same system, without really coming out and crassly lecturing his listeners on that point.

But Kanye isn’t just about debasement. “All of the Lights” is basically the pinnacle of all the big business manufactured pop that shows up on television-promoted “talent shows” and top 40 radio. It has a minimalist melody — with an emphasis on melody more than what hip-hop is traditionally about. But it is elusive. The song lacks a clear interpersonal dynamics narrative like most of these songs. It blurs the lines between ghetto life and stardom. But it does so while beating the pop market at its own game, having as catchy and hummable a hook as anything in contemporary pop. If he didn’t pull off catchy pop hooks like on “All of the Lights” it would be all too easy to dismiss everything else on the album. Kanye doesn’t stand apart from that aspect of the music industry. He wrestles with it as he also heads in other directions.

“Hell of a Life” raps to the melody of Black Sabbath‘s “Iron Man.” Like a lot of the songs (“Blame Game” etc.) there are elements of misogyny and room to question why that is a part of what the protagonist is doing. Kanye may be no feminist, but he lets the listener wonder why he isn’t.

Of course, the other thing about My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is that it sounds fantastic. It is the absolute state-of-the-art of what hip-hop and pop music can do with modern recording technology. And despite the bloat of an album that seems much longer than it needs to be, it hardly ever wavers and never seems to run out of material the way albums over 70 minutes usually do. If Bob Dylan needed a huge ego to do what he did in the 1960s, and David Bowie succeeded precisely because of the pomposity of his glam rock pretensions in the early 1970s, then Kanye taps into some of that here for a new era. This is a spectacle, a captivating one, and Kayne makes the most of capturing the audience’s attention to actually raise some worthwhile questions while you can’t seem to tear away. So if you leave wondering why you bother being stuck listening to someone who sounds like an annoying stockbroker, that seems to be the point — to dissolve the specter of meaning of celebrity from the inside, dismantling the very frame of reference that intimately links celebrity status to all the off-putting “stockbroker” qualities.