Bridget St John – Songs for the Gentle Man Dandelion DAN 8007 (1971)

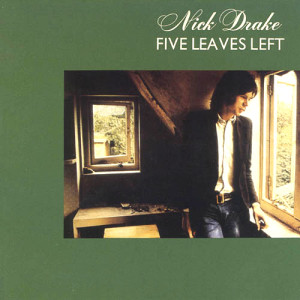

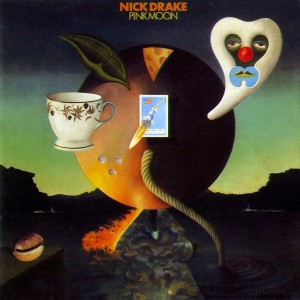

Bridget St. John’s Songs for the Gentle Man is frequently compared to a number of other folk/rock artists of the late 1960s and early 70s. The most common is that she sounds like a combination of Nico and Nick Drake. Others cite Judy Collins‘ work with Joshua Rifkin on albums like In My Life. One could even throw in Vashti Bunyan. The Nico comparison is mostly right with respect to tone and timbre of their voices, especially when comparing Nico’s debut album Chelsea Girl. Both had a husky, deep voice; hardly identical, but Nico is still the closest comparison among reasonably well-known folk/rock singers of the era. Nick Drake combined folk and orchestral arrangements, but he had a surprisingly different approach, with melancholy that is scarcely present with St. John — it’s a somewhat strained comparison. Judy Collins is the most important reference point. She pioneered a type of folk that was kind of the obverse of Joan Baez. Baez made music that combined bel canto singing (with shrill, heavy vibrato) with homespun folk guitar playing. Collins instead used elements of showtunes to shape a singing voice that was still based in homespun folk music, then added refined Euro-classical orchestration (by Rifkin). The problem was that Rifkin was inconsistent, and, sorry to say, operating somewhat at or beyond the limit of his abilities. St. John took a similar baroque sensibility, through orchestration by Ron Geesin and John Henry, and applied it over homespun (yet adept) vocals and guitar. Unlike Baez, who often seemed to compromise the folk elements to the dictates of established operatic pop forms, St. John (like Collins) tries to keep each sphere intact. The strings add sophistication without diminishing the expressiveness of the vocals. And the arrangements and orchestration on Songs for the Gentle Man are uniformly excellent. This style of orchestrated folk would slip away in a few years, as the rock music came to dominate folk music. Then the approaches of Paul Buckmaster (with Shawn Phillips, etc.) and Tony Visconti (with T.REX, etc.) would make similar strides in combining orchestration with rock, albeit in a very different way.

Speaking about the song “City-Crazy,” St. John said that she “sometimes felt not ‘stop the world I want to get off’ but ‘slow the world down, I want to stay on!'” It reflects the entire album as much as that one song. This interest in a slower pace of life is a bit like Vashti Bunyan’s musical portrayal of radical rural simplicity. But St. John has a more urban sensibility, just slower than the bustle of actually existing urban life.

Songs for the Gentle Man was not a revolutionary album, but it took ideas that were percolating in the folk/rock scene and perfected them. This is not a particularly immediate album. It may take a few listens to appreciate fully. But there are few better listening choices for a bright summer morning or afternoon (this is definitely not nighttime listening material).