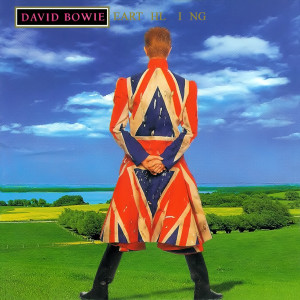

David Bowie – EART HL I NG Arista 7432143077 2 (1997)

I’ve gone through many phases with this album, Earthling. I rather liked it at first, but then later on it felt dated and I couldn’t stand it. Giving it another go during a period of revisiting some Bowie recordings, it seems like one of his better late-career efforts. It’s clear he’s trying, though sometimes he’s trying too hard to seem “with it”. He jumped aboard the electronica bandwagon, deploying industrial drum ‘n bass, or whatever they were calling the microgenre that month. The whole affair seems a bit uneven, and it’s hard to do anything with “The Last Thing You Should Do” and “Law (Earthlings on Fire)” but cringe. Yet there are a fair number of high points, the highest being “I’m Afraid of Americans,” a song that can rub shoulders with any of Bowie’s best songs from any era. Sure, I was probably right when I though this would sound a little dated, but Bowie seems to be legitimately enjoying making this music most of the time (even if “Looking for Satellites,” “Dead Man Walking” and “Seven Years in Tibet” reveal him to be getting lyrical inspiration from watching movies and satellite TV). It shows most in his vocals, which have both an energy and nuance that he hadn’t mustered in while. One last note: isn’t it odd that Bowie’s better work has come during the periods when he’s been married?