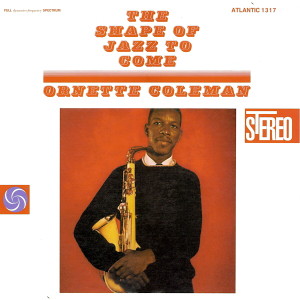

Ornette Coleman – The Shape of Jazz to Come Atlantic SD 1317 (1959)

Ornette Coleman’s second album as a leader has the bold title “The Shape of Jazz to Come” (selected by the producer Nesuhi Ertegun) and few albums earn such bold statements as this one does. His music has always pushed anarchic tendencies. In 1959, he was still accustomed to the format of bop and hard bop, and those habits of thought definitely inform this music. The songs open with a head played by the entire group, and the performers trade solos before returning to the head. Now, the catch is that both the head and those solos don’t sound at all like any others around in 1959, excepting perhaps a few forward-thinking performers like Cecil Taylor and Sun Ra.

The opening “Lonely Woman” is perhaps the single best-known Coleman composition. The sour, dissonant melody played by Coleman on his plastic alto sax (he was unable to afford a metal one in his early career) and Don Cherry on cornet stumbles along, falling forward. Ornette said he composed the song after coming across a painting of a wealthy woman who looked sad to him. As was Ornette’s key approach to music, the song features unusual improvisation with the players free to melodically improvise without fixed harmonic relationships to each other or a tonal center. The result is that music theory and the limiting rules inherent in that kind of knowledge are subordinated (if not completely discarded) to the ideas (Ornette referred to “emotion”) that the performers hold form in their performances. The performers may have been habituated to the format of bop jazz, but they were clearly heading in a completely different direction.

When Ornette plays a slurred trill on “Eventually,” he almost sings into his horn in a way that drives home the new set of values embodied in the music. For if anything, Ornette’s music represented the expression of different political choices that couldn’t be expressed in the old forms. So he crafted new ones. When you hear this, note how fun and happy much of the music is at its core. In a context in which feeling good expressing yourself without guilt is deemed unacceptable, then going ahead is radical. But with Ornette, he does this amazing thing. He fights for this arena to express things in music without positioning himself as some kind of messiah-like figure with unique talents. The way he plays makes you think you could maybe do it too. The Italian filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini said in an interview, “My nostalgia is for those poor and real people who struggled to defeat the landlord without becoming that landlord.” This is precisely what Ornette’s music represents, and why it seems right to have a certain fondness for The Shape of Jazz to Come decades later. You can gauge anyone’s politics by how they react to this album — those who want to retain modes of domination in society won’t take a liking to it. And people who claim Ornette had limited abilities should be asked: by whose standards?

It is a commentary on the lack of meritocracy in the world, but Ornette owed much of his “break” into the professional music world to John Lewis of The Modern Jazz Quartet, who helped Ornette find gigs, a record label and gain some kind of credibility from an endorsement by an acknowledged star. Of note, though, is that it was a respected musician like Lewis, who had a masters degree in music and taught music at prestigious conservatories associated with European classical music, had enough credentials to allow him to support Ornette’s music without being criticized as not knowing what he was talking about. Other self-taught musicians who lacked such institutional credentials would risk being labeled as know-nothings for supporting Ornette’s music. But, all that aside, Ornette did well with the opportunities available to him.

With his time in the spotlight on Atlantic Records, Ornette recorded music as radical as anything heard before in jazz. Musicians who worked their entire lives to perfect their skills playing chord changes were probably chagrined to see Ornette throw all that out and place an emphasis on other elements, improvising with composition as much as interpretation in his solos. The more open-minded found in Ornette a visionary. No doubt, Ornette had a much more individualistic conception of musical performance than most listeners (and society writ large) were ready to accept in the late 1950s, which is to say he thought everyone should have much more latitude to express themselves in their own ways without deference to established modes of expression (which invariably are the products of institutions that reproduce social hierarchies). So perhaps under the old critical standards this music is played “poorly”, but the point is that the old standards are self-serving and this music steps outside them.

Ornette plays in a harsh way, with a sound always about a quarter cent sharp. This was partly due to playing a plastic Grafton saxophone. But even after he bought a new metal one, his sound retained its biting qualities. It was simply his sound. Don Cherry played cornet in a similar way. He had a knack for keeping to Ornette’s melodic lines with a characteristic phase-shift, always a split second off of Ornette’s timing. Bassist Charlie Haden plays with a warm, R&B tinge, occasionally playing double stops (“Focus on Sanity,” “Chronology”) in a fluid, buoying way that contrasts with the dissonant horns. Drummer Billy Higgins is basically a very forward-thinking bebop drummer, who grew into the free jazz movement. His playing is rather rooted in bop structure here, which is a major reason why The Shape of Jazz to Come is an easier listen than some of Coleman’s later works with more free-wheeling percussion and rapidly shifting polyrhythms.

“Peace” is the longest track here, and the group plays with a lot of space, at a slower tempo. The song says as much in the notes left out as in the ones played. Is peace about their being less in the world? Less what? Take a listen and wonder.

The Shape of Jazz to Come is certainly one of Ornette’s most likable albums. He made more challenging ones, in hindsight at least. The vestiges of bop structures make this a bit less demanding, without being a cake walk. Any jazz education should include this album as essential listening. Yet this is also a work well worth revisiting. If the flaws of this album are the ways it can’t get past bebop structures entirely and the overabundance of optimism about unleashing music this radical, those are as endearing as flaws come.