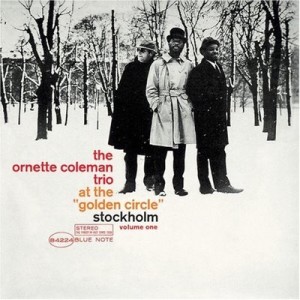

The Ornette Coleman Trio – At The “Golden Circle” Stockholm, Volume One Blue Note BST 84224 (1966)

In 1962 Ornette briefly retired from recording and public performance. He returned to public performance in 1965, after teaching himself violin and trumpet, and then spent the remainder of the decade bouncing between record labels. He recorded a number of albums for Blue Note in the late 60s, as that label started to fade from prominence. Both just before and after his retirement he worked with a trio featuring Charles Moffett on drums and David Izenzon on bass. Most of the Blue Note recordings are considered somewhat second-rate entries in the Coleman catalog. But two volumes of live recordings from Sweden at the “Gyllene Cirkeln” club have definitely withstood the test of time and can stand alongside Coleman’s best work. It was Ornette’s first tour of Europe.

The music here is a refinement of what Coleman did in the late 1950s and early 60s with his combo that featured trumpeter Don Cherry. There is a lightness and optimism in this music that is rather rare in free jazz circles, where dour seriousness all too often predominate. Coleman plays many songs here with melodies that could well double as nursery rhymes. The sparseness of the trio format, without any other horn to play harmony with Ornette, and with Izenzon and Moffett both playing in ways that recall standard bop jazz, make this music a bit less demanding on the ears than Coleman can sometimes be. But for all those reference points, this music also reflects the growth and change in Coleman’s music from the preceding years. This is transitional music. The amazing thing about Coleman is that no matter how radical his approach to music was, it wasn’t static. Here, the radicalism comes in a most unexpected way. It introduces complex, novel structures by appearing to do anything but that.

These songs often find Coleman playing for a long time, without repeating himself and without relying on another wind player to add independent melodic statements (much like on Chappaqua Suite, recorded earlier the same year). He also throws in short little riffs of surprising complexity. No, this is not a performer limited to simply melodies; this is a performer choosing to play them. The effect all this brings about in the music is subtle. At any moment, Ornette doesn’t seem to be playing differently than he was five years earlier, but he’s playing that way for so much longer without tiring that this represents a whole new level of that same type of playing. Reaching that new level opened up new horizons for compositional structures in the music. The group doesn’t return to “heads” (group statements of a theme) in a planned way, as on early Coleman recordings. Izenzon and Moffett are largely free to solo simultaneously with Ornette — though both are fairly restrained players who do so without much flash or pageantry. This becomes the heart of Ornette’s musical theory of “Harmolodics”. This is a trio of musical equals. None of the instruments is privileged over the others. Moffett plays a key role in this. His drumming is bop-inflected, but also more skittering and decentered. He drops a few bass/kick drum “bombs” like Art Blakey, but he works in a lot of hi-hat rides and runs on his tom drums during Ornette’s playing time, with a touch so light and effortless that he turns what would be a Blakey solo feature in a Jazz Messengers performance into supportive “accompaniment” that suits concurrent playing by the other trio members. As the players work together, they are able to react and shift directions as a unit, without tearing the fabric of the performance apart abruptly. Rarely does jazz performance this angular and sharp sound, if not smooth and easy exactly, at least as smooth and well-incorporated as it does.

There is an earnestness in this music that makes it difficult for even Coleman detractors to bag on it. At The “Golden Circle” Stockholm, Volume One is certainly Coleman at his most approachable. It is probably advisable for newcomers to his music to start closer to the beginning, with some of the Atlantic recordings; however, this live set makes for an excellent second course, so to speak. His music reach a pinnacle of complexity in the coming decade, as he began to realize works at the furthest reaches of what his “harmolodics” concepts suggested in music.