This Is 40 (2012)

Universal Pictures

Director: Judd Apatow

Main Cast: Leslie Mann, Paul Rudd, Megan Fox, Jason Segel

Judd Apatow’s movies are very much within the mainstream cultural sphere, but within the necessary constraints of Hollywood, his films often explore the limits of doing what you love and how his characters can’t (or choose not to) enjoy themselves. Put another way, the characters go through this process of trying to change their desires, to go from being, essentially, adolescent young adults, to mature adults. C.G. Jung termed this “individuation”, the kind of “second puberty” that happens at age 35-40 (if it happens at all) where the individual is (re)integrated into a social collective — illustrated by Goethe‘s Conversations of German Refugees: Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years or The Renunciants. (Goethe was a huge influence on Jung, inspiring many of the latter’s theories of analytic psychology).

Reviewer Onethink summarized the film this way in a review:

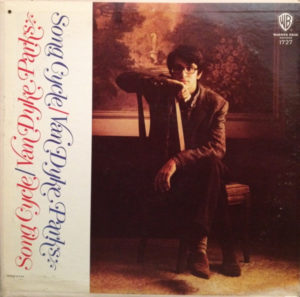

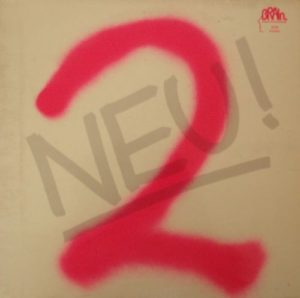

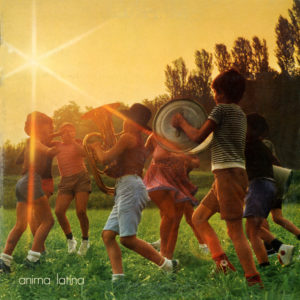

“Debbie and Pete (Leslie Mann and Paul Rudd) live in the American dream: they have a luxurious house, flash cars, two daughters who go to a nice middle class school, they own their own businesses – and the businesses are hip and trendy: she runs a chic fashion outlet, he runs a record company. But not everything is rosy. The businesses are failing. Debbie has deep anxieties about growing old – so she lies about her age and has a personal trainer and begins faddy eating regimes: all the things middle class Americans should do. And, typically for a male Apatow character, Pete has certain maturity issues: is his record company not so much a business as a strategy to still feel young and hip? As parents they go from the lenient to the draconian. And their fathers bring a couple of variations: both are monstrous, one clinging and dependent, a nightmare image of a ‘failed’ adult, the other aloof and distant, a nightmare image of a ‘successful’ adult.”

The parts about work are interesting. Miya Tokumitsu wrote the most popular article ever on a magazine’s web site, and later expanded that article into a book, about the trouble with the injunction to “do what you love” for work/career. Making much the same point more generally, the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek frequently states that the injunction of contemporary ruling society is to “enjoy,” that the superego perversely demands that we enjoy that which is really our duty, traumatically and painfully depriving us of free will to choose what we enjoy at the very point a choice is seemingly offered, stigmatizing us. The characters in This Is 40 seem to have the jobs/businesses they want, or are supposed to want. But they are forced to make money to support an upper middle class lifestyle. Is it that they want these jobs, specifically, or want these jobs to support the lifestyle that they really want? Or do they want a different lifestyle altogether? Is it that everyone around them wants them to have their lifestyle, forcing it on them? Is it possible for them to want something apart from what those around them want them to want?

If the central parts of the film are politicized — and why not look at the film that way? — then the conservative view is to dislike the main characters Debbie and Pete, the centrist-liberal view is to sympathize with them, and the leftist view is to appreciate them as unreliable narrators of sorts. The conservative view would be that these failing entrepreneurs are properly subject to market forces, and any of their failings in the market are their personal failings. The film is wrong then, in a sense, in sympathizing with the ambitions of the failed businesspeople, who fail because they should — they are failures. And the characters are unsympathetic because they turn against “traditional values.” The centrist-liberal view is to value the many varied people in the film, to each their own (a multicultural, identity politics paradise), and the conflict of the characters not fulfilling their promise and expectations needs to be resolved. The film is correct, therefore, to sympathize with its characters. Everyone deserves to be happy. The left view, however, sees the main characters as not particularly likeable, or at least as Onethink says, monstrous in their way. These are just a bunch of stupid people, as stupid as any, and the challenge is how to educate them to accept responsibility for creating meaning in their lives — even their professed desires may be unreliable or stupid. This reads the film to the left of the film’s ostensibly “professional” Hollywood perspective, which is centrist-liberal, by saying the main characters aren’t really as likable as they are presented to be. While Apatow doesn’t go as far in rehabilitating antiheroes as, say, Pasolini with Accatone or Korine with Gummo, then he at least takes a Hollywood movie and cracks open the possibility for this perspective from within it (and he does so with a bit more finesse than, say, The Company Men or just about any “little” Hollywood side-project film with big-name actors but little marketing).

The film has very realistic main characters, and the acting is generally excellent. Really, there are great, subtle moments from Mann and Rudd all over, helped by very strong screenwriting. The very dull moments actually help that along — the quirks of hiding from family members in a shared house, obsessions with material things, resort to therapy/counseling techniques. Some of the peripheral characters are a bit thin and one-dimensional, or implausibly exaggerated. But these minor characters are mostly present to add humor to the film, setting up jokes and gags. But this is a comedy, and it probably wouldn’t succeed as being one without those set-ups, however artificial. And there are mostly white people in this closed universe — not to say that there is something inherently wrong with that, but the restricted experiences of white people form implicit boundaries around the film’s ambitions and perspective. Give this credit though for a fairly balanced mix of male and female characters with substantive parts, and not just of a romantic type — these female characters engage each other without any males present.

The film’s ending is archetypical Apatow: it is a “Hollywood” ending, complete with facile, happy resolution of the major plot points and conflict, and yet, it actually is not entirely that at all. The film ends with a bit of a “fuck it all!” attitude, but without any guilt about it. The two main characters, at least, tentatively accept that there is no one (or no thing) that will provide meaning for their lives, or their relationship. As their fathers (Albert Brooks and John Lithgow) loom larger in the second half of the film, the two main characters Debbie and Pete recognize that their parents can’t be faulted for failing to provide meaning for them — nothing and no one can do that. Even the angst about selling their upscale house to make ends meet is an admission that having that particular material possession won’t validate their existence. But rather than wallowing in existential dread, they reform and reassert their couple relationship, and their family structure. This is what philosopher Alain Badiou calls a “two scene”: the positive existential project to see the world from the point of view of difference rather than identity, “to construct a world from a decentered point of view other than that of my mere impulse to survive or re-affirm my own identity.” This is basically a specific type of individuation. The ending isn’t the film’s strongest section, but it manages to make a compromise with the happy ending in a way most Hollywood films can’t (think about how As Good As It Gets sets up a premise for an inevitable downer ending, then winds up with the usual happy one anyway). The small kernel of radicalness in this film is that even though the married couple chooses to stay together at the end, they get there through free will. They don’t just resign themselves to social dictates. Instead they overcome the injunction to enjoy what they are demanded to do, and instead make their own choice, which happens to be to maintain a stable nuclear family, even if they aren’t strictly happy as a result — they end up with a space where they don’t have to enjoy their social duties. This is in contrast to, say, the rather one-dimensional character Desi, who is totally confined to play a particular role, without free will (note how Debbie declines that lifestyle in the film). Returning to Zizek, he says, “The problem today is not how to get rid of your inhibitions and to be able to spontaneously enjoy. The problem is how to get rid of this injunction to enjoy.” If there is danger in seeing the film’s ending as radical (think of the questions raised about asserting that a woman shopping is a feminist act), then at least the film as a whole provides enough to make the ending a kind of vector rather than a static point, it occupies the same space as that static point but it points somewhere, from where it was to where it is going.

This is 40 is a much better and deeper film that it seems. Definitely Apatow at his best.