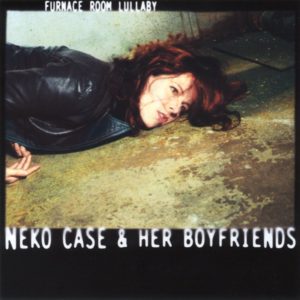

Neko Case & Her Boyfriends – Furnace Room Lullaby Bloodshot BS 050 (2000)

Neko Case & Her Boyfriends’ second album Furnace Room Lullaby is a calculated take on country music that manages to be more than the sum of its parts. This is a real country album. But it only arrives at the realness of country music in a circuitous, even backwards way.

The album consciously stakes out a range encompassing crafted ballads (“South Tacoma Way,” “Porchlight”), sly waltz (“Thrice All American”), driving rockabilly (“Whip the Blankets,” “Mood to Burn Bridges”) and hazy lounge jazz (“No Need to Cry”). The album limps most of the way, with a kind of contrived indie rock vision of what country music is supposed to sound like, complete with all the clichés. That is the best part!

All sorts of country affectations are employed across the album, like slide guitar and fiddle, but most notably the rock-styled rhythms from the drums and Case’s countrified vocals that sound nothing like those of a southerner. She has a distinctive way of singing sustained, crescendo-ed notes in a dramatic way, often book-ended by clipped phrases with half-yodeled melisma, and also frequently bolstered with washes of legato keyboards or backing vocals. Yet, the album succeeds precisely because the illusion of authenticity fails. No matter what urban mannerism she laces through her country songs — the essence of insurgent (alt) country is using the devices of country music usually directed to rural audiences to appeal to urban middle-class audiences — something persists that seems to cut through those very mannerism. It is somewhat of a frequent occurrence that “rock” musicians make country music to tap into its supposed authenticity, at least implying that authenticity is lacking in rock music, but Furnace Room Lullaby preempts that by its obviously artificial performances. And, really, country music is a set of arbitrary and therefore artificial devices just as much as rock music. What emerges then is something else, an existential denial of all authenticity and a kind of triumph of crafted artifice that builds up an approximation of the idea of authenticity through non-authentic means. Is Case then simply pretending to be what she really is? This is a really intriguing way of staging what are songs — all excellent compositions mind you — mostly about personal identity forged in the crucibles of relationships, a hometown, and a trajectory of subtle but undeniable ambition. The underlying question that looms across the entire album is, “Who am I?” Case never ventures an affirmative answer, but keeps pondering that question over and over again.

Neko forges music from her Pacific Northwest roots with a cautious nostalgia. “South Tacoma Way” is the album’s epic story of loss. Of course themes of heartache and resignation come up is every song; some call it “country noir”. These songs make your problems seem either easier or shared. The highlight of the album may well be “Thrice All American,” about the city of Tacoma, Washington, Case’s adopted hometown and winner of the All-America City Award three times — but the song is also a waltz.

Neko Case & Her Boyfriends manage to combine all kinds of influences. It all works. At this stage of her career, before fully succumbing to the banality of indie rock, Neko was as brave as any singer-songwriter out there (though most of these songs were written with collaborators). She was okay with being a little like her heroines — Poison Ivy from The Cramps, etc. On “Guided By Wire” she tells of “those who’re singin’ my life back to me.” It is that binding of her identity to those who (circularly) give her meaning that raise the stakes here. There really is no “true” identity, just tentative links to people and places, many of them commonplace. Country music at its best always made that same point.

Recommended.