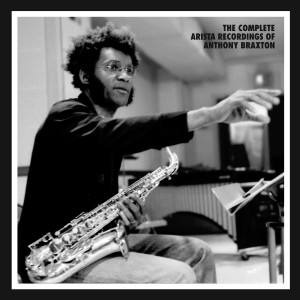

Lotte Lenya – Lotte Lenya singt Kurt Weill Philips B 07 089 (1955)

Lotte Lenya was, in a word, inimitable. That voice, so frail yet so unshakable, gave us the definitive interpretations of Kurt Weill‘s music. Lotte Lenya singt Kurt Weill was recorded in 1955 as her career saw a revival thanks to a new English-language production of Brecht/Weill’s “Threepenny Opera” by Marc Blitzstein at the Theatre de Lys (co-starring Bea Arthur, Ed Asner and Jerry Stiller). She recorded in Berlin, returning for the first time in twenty years. That environment was likely crucial to the record that resulted. A lot had changed in those years.

First some history. Germany and Prussia, under Kaiser Wilhelm II, provoked the Great War (World War I) by seeking to enjoy the same economic and political privileges that imperial powers like France and England sought to reserve for themselves. Germany/Prussia was eventually defeated due primarily to the fact that the United States lent its fiscal and manufacturing support to the side of the Allies — in spite of the Bolshevik Revolution that withdrew Soviet/Russian troops from the ridiculous conflict (not to mention allowed the publication of the secret Allied treaties in Pravda). That particular war lead to abdication by Wilhelm II in 1918, and later the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The treaty has lived in infamy, as it memorialized the old grudges held by England/France against their counterparts with oppressive reparations imposed on the Germans/Prussians. To the chagrin of the Allies, American boorishness reared its head as the United States refused to treat Allied support as wartime grants not to be repaid (as was long tradition among warring nations) but instead as loans to be repaid (thanks to American intransigence and other factors like inept British negotiation, the terms of the loans worked out after the war were, to say the least, oppressive). (Read about this in Michael Hudson‘s Super Imperialism: The Origin and Fundamentals of U.S. World Dominance (New Edition)). This set the stage for Weimar Germany, the Republic established out of the confusion following Wilhelm II’s abdication that lasted barely more than a decade until the Nazis rose to power in 1933.

Weimar Germany was a strange and unusual thing. German reparations were so oppressive as to eliminate the possibility of economic recovery. Moreover, repayment of the outrageous Allied loans was realistically tied to and dependent upon the payment of German reparations — despite self-serving American denials. In that economically savage context, with recovery impossible, the German people lived a chaotically vibrant but inescapably desperate existence. The classic novel of the Weimar era, Alfred Döblin‘s Berlin Alexanderplaz: Die Geschichte vom Franz Biberkopf [Berlin Alexanderplatz: The Story of Franz Biberkopf], portrays the times as well as anything (the relatively lazy can instead watch the 15+ hour adaptation Berlin Alexanderplatz by New German Cinema director Rainer Werner Fassbinder). Like the novel’s protagonist, good intentions fall prey to grim realities, and crime and prostitution become familiar responses to a life of limited opportunities. Disgusting Nazi propaganda becomes a repository for misguided resentment and wounded pride, or, in Biberkopf’s case, simple gullibility.

Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya (married to each other twice) rose to prominence in this Weimer era. Weill was a composer like Erik Satie or George Gershwin, seeking to bridge the gap between popular music and formal, classical composition. Weill has been frequently compared to Mozart for the direct, lyrical qualities of his music, so simple but with a rich and nuanced depth underneath.

The music of this album comes from a number of Weill efforts: “Die Dreigroschenoper [The Threepenny Opera],” “Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahogonny [The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahogonny],” “Happy End” and “Das Berliner Requiem [Berlin Requiem]” with texts by Bertolt Brecht and “Der Silbersee, Ein Wintermärchen [The Silverlake, A Winter’s Tale]” with texts by Georg Kaiser. What makes these particular recordings so wonderful is that the music is an honest and grim interpretation of Weill’s music. When he originally scored “The Threepenny Opera,” he did not use a full orchestra. Instead, the music was for seven musicians asked to play a total of twenty-three different instruments. Alex Ross, in The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, writes that “by asking his performers to take on so many roles, Weill guarantees that the playing will have, in place of soulless professional expertise, a scrappy, seat-of-the-pants energy.” In that, one finds some of the essence of Weimar Germany, just like Franz Biberkopf the working-class protagonist of Berlin Alexanderplatz shifts his career among that of a pimp, necktie clip salesman, shoelace drummer (door-to-door salesman), newspaper barker, burglar. Biberkopf’s determined but futile individualism has the same spirit as in Weill’s ingenious, street-wise compositions.

These particular recordings, with instrumentation like a ragged banjo and warbling organ on “Moritat vom Mackie Messer [The Ballad of Mackie the Knife],” or an out-of-tune piano on “Bilbao-Song,” are true to the original Weill vision. It is great that Brecht and Weill’s song has become something of a standard, but the slick renditions of Louis Armstrong, Bobby Darin, Ella Fitzgerald and others miss something when the sense of fear and uncertainty is swept away with a very refined pop/jazz arrangement. These 1955 recordings bring out something in Lenya’s voice too. Recording amidst a once-grand city ruined by Allied terror campaigns, the sense of grim desperation that so characterized Weimar Germany just below the surface in the 1920s is palpable in her rough-hewn and gently aged voice. The Great War (WWI) killed untold people, but the civilian infrastructure of Europe was largely untouched. World War II changed that. American callousness led the Air Force to switch to terror bombing of civilian targets starting with Berlin, then on to the fire-bombing of Dresden (memorialized in Kurt Vonnegut’s The Slaughterhouse Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death) and Tokyo, the dropping of napalm on Royan, France (read Howard Zinn, who participated as a bombardier), and culminating with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (later revealed to have been unnecessary in view of a Japanese willingness to surrender, but advanced to try to intimidate Stalin; read Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing The Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, Gal Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb or Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century or even Peter Kuznick) — for their part the other war powers had their own instruments of terror, from the German Paris Gun and V-1 and V-2 rockets to the Japanese explosive devices delivered to mainland North America on balloons carried in the jet stream. In spite of the Wirtschaftswunder, or German “Economic Miracle” of the post-WWII years made possible by cancellation of German internal debt (and with U.S. aggression in the Korean War serving to bolster the German economy), Berlin was still in visible ruins when Lenya returned (for more context, watch Fassbinder’s Die Ehe der Maria Braun [The Marriage of Maria Braun]). However, the Berlin Wall, erected by the East to keep out CIA saboteurs (read William Blum Killing Hope: U.S. Military and C.I.A. Interventions Since World War II (Updated Through 2003)), was still six years away.

In such a brutal century, Brecht and Weill’s murderous Macheath, the central character of “Mack the Knife,” seems like a sign of the times. “He has his knife,” so the lyrics tell us, “but / no one knows where it may be,” like the airplanes and rockets bringing down fire on civilians, or the economic subterfuge of government reparations and debt that invisibly suppressed the Germans, French, and English in the Weimar era. That is the way of Brecht’s theatrical vision. Songs like “Alabama-Song” too (with lyrics some allege were co-written by Brecht’s girlfriend Elisabeth Hauptmann) capture pub life (during an era of American Prohibition), with deadpan refrains of “Oh don’t ask why / Oh don’t ask why.” The words also tell of looking for a dollar, or else they, the singers, “must die.” The contrast of the merciless themes and the seemingly light, sing-along performance throw light on the odd complexities of modern life. Times have changed less than it may seem, only the origins of those realities are more concealed than ever.

Later attempts to make music ostensibly like this so often resort to irony. There is no irony here. There are contrasts, and dialectical devices, but everything is a direct representation of what is expressed. This is music like little else.