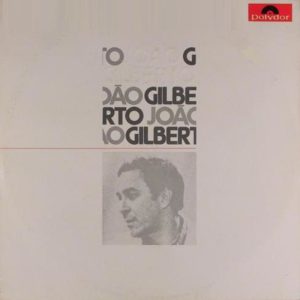

João Gilberto – João Gilberto Polydor 2451 037 (1973)

Gilberto is considered the father of bossa nova. The style evolved out of samba, but with a minimalist aspect that used musical gestures to imply elements beyond the explicit content. There was less emphasis on rhythm and more on harmony and melody, drawing influence from jazz in some respects. His singing is almost a whisper, slightly nasal, and is free of vibrato. Bossa nova emerged in the 1950s (some claim the scene coalesced in the living room of Nara Leão‘s parents’ home). It was music of the bourgeoisie, popular among the college-educated, with an emphasis on introverted, existential and personal obstacles. It became an international craze in the 1960s. Yet by the early 1970s, bossa nova had ceded popularity in Brazil and the rest of the world to other styles. The Brazilian junta was in power, and under President Médici the economically polarizing “Brazilian Miracle” was underway, punctuated by the 1973 oil shock. In the United States, the Powell Memo had recently been published and the neoliberal era was finding its feet. The Gang of Four was still leading China’s Cultural Revolution, but President Richard Nixon had met with Premier Zhou Enlai the year before — Nixon had already a few years earlier met with Elvis and gave him a a badge from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. It was chaos everywhere. The timing was perfect for a resurgent Gilberto.

The album comes across as Gilberto performing solo. Nonetheless, Sonny Carr appears regularly on light and gentle percussion, and Miúcha (Gilberto’s wife or girlfriend at the time) provides vocals on one song. Like many Brazilian musicians, Gilberto had multiple self-titled releases. This one is sometimes dubbed the “white album”. The oft reclusive Gilberto had lived in the United States through much of the 1960s, then moved to Mexico for about two years, and then moved back to the United States where he lived at the time this album was recorded, supposedly in New Jersey; he returned to Brazil in 1980.

In many ways, this is a flawless album, as much as such a thing is possible. Gilberto has a lightness to his voice and guitar playing that speaks to the resilience of inner resolve. The recording fidelity is excellent (Wendy Carlos served as the recording engineer and Rachel Elkind the producer). If the sunny existentialism of bossa nova was always one of its defining and most appealing features, this is an album that confirms relevance beyond its faddish commercial peak.

The opener is Antônio Carlos Jobim‘s “Águas de Março” (“The Waters of March”), one of the most highly acclaimed Brazilian songs of its time, performed with a placid, self-content attitude toward the meaningless cycles of nature and the seasons and fully embracing the arbitrary, stream-of-consciousness wordplay of the lyrics. It is followed by Gilberto’s own “Undiú,” with mostly wordless vocalizations and singing that approaches guttural-sounding throat singing. This leans toward a Zen-like attitude, contemplating the universe and offering statements outside language. “Eu quero um samba” opens side two of the original LP, and has some of the most insistent guitar playing on the whole album, bolstered by Carr’s lightly tapped percussion. Despite the minimalist instrumentation, there is much happening on this album, which is tinged with nostalgia and sentimentality (a song about Gilberto’s young daughter, “Valsa (Como são Lindos os Youguis) (Bebel),” and a version of Gilberto Gil‘s “Eu Vim da Bahia” [“I Came From Bahia”]), yet also dry and aloof as well, with the vibrato-less vocals and a sometimes cloistered attitude.

If one word describes Gilberto’s musical approach, it would perhaps be “nuanced.” This is part and parcel with the leisure class undertones of the entire bossa nova genre. And yet, this music is an ideal expression of a relaxed, peaceful attitude toward a stressful and even harrowing urban bourgeois existence. This is just one of the irreducible knots at the heart of bossa nova. These knots lend the tension that is evident in the rhythmic construction of João Gilberto’s music. As one writer put it, “The voice pulled in one direction, the beat in another. The combination was mesmerizing and highly addictive, refreshing and modern.”

If all of Gilberto’s music lends itself to a kind of cultural nationalism, the artist’s reclusive tendencies and withdrawal from the trappings of celebrity suggest something else altogether. Is it a false sense of purity? No, not at all. In a paradoxical way, Gilberto’s dogged pursuit of his own muse while disengaging from a world taking disastrous turns for the worse is actually about making in a crucial statement in the face of cruelly empty formal options. This position lingers:

“the danger today is not passivity but pseudo-activity, the urge to ‘be active,’ to ‘participate,’ in order to mask the vacuity of what goes on. People intervene all the time. People ‘do something.’ Academics participate in meaningless debates, and so on. The truly difficult thing is to step back, to withdraw.” (On Clinton, Trump and the Left’s Dilemma).

Stated in another and more general way, this sort of passivity can really be a form of action:

“the very passive ‘withdrawal’ by means of which [a] thought ‘secedes’, ‘splits off’ from its object, acquires a distance, violently tears itself off ‘the flow of things’, assuming the stance of an ‘external observer’; this non-act is its highest act, the infinite Power which introduces a gap into the self-enclosed Whole of Substance.” (The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Center of Political Ontology)

If the Brazilian tropicalistas sought a new internationalism in the late 1960s and early 70s, João Gilberto’s music here was substantively taking another tack, and yet making João Gilberto in the United States with electronic music pioneers hardly seems lacking in internationalism… The key to it all is the reaffirmation of everything that Gilberto’s music promised in the late 1950s, that not in spite of but because of everything that happened in the interim, the original vision of bossa nova was a vital and radically new historical event, proven through its repetition and a look back that shows its truly original worldview to have gone beyond its causes and influences, an achievement and social rupture that was somehow also impossible in its time.

João Gilberto is an album that deserves a listen, or many.