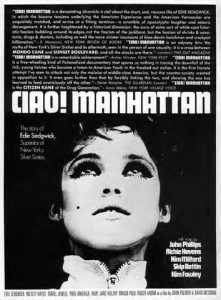

Ciao! Manhattan (1972)

Maron Films

Directors: David Weisman, John Palmer

Main Cast: Edie Sedgwick, Wesley Hayes, Isabel Jewell

The mysterious, tragic and often disturbing world of Edie Sedgwick is plastered across the screen in John Palmer and David Weisman’s Ciao! Manhattan, a film almost as mysterious and tragic as Edie herself. The great Jonas Mekas called it “the Citizen Kane of the drug generation.” Even more so it’s the Lola Montès of the drug generation. Opinions of the film vary for an understandable reason. There remains a fundamental, unresolved conflict at the bottom of the film: Edie Sedgwick.

Who was Edie Sedgwick? She came from an extremely wealthy family in California and as a model landed amidst Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd in the mid-Sixties. She was, to put it bluntly, a dazzlingly gorgeous icon of that era. But her moment in the sun didn’t last. Edie’s lifestyle was combustible. She died shortly before the film was ready for release.

Edie inspired many artistic creations. “Femme Fatale” is the Velvet Underground song about Edie written by Lou Reed at Andy Warhol’s suggestion. On the 1969 Velvet Underground Live With Lou Reed the song is introduced by Reed saying: “This is a song called ‘Femme Fatale,’ which we wrote about someone who was one. . . And will one day maybe open up a school to train others.” On the Velvet’s Bootleg Series Volume 1: The Quine Tapes, Reed comments that maybe the Warhol Factory environment had nothing to do with Edie’s condition. It is also rumored that Bob Dylan wrote “Just Like a Woman” for her. In Warhol’s a: A Novel, Edie is “Taxine.” A common sense of Edie emerges. She had immense power over people to get what she wanted by creating hope—a tangible, real hope — that seems to have drawn people to her. In the end, these manipulations worked too well. Edie was guilty of having innocent dreams, too grand and too destructive to ever last.

Weisman calls Edie “Icarus” and the Central Park “Be-In” on Easter Sunday of 1967 was when she came too close to the sun, melted her wings and began to fall. That began a long period when Edie shuffled from hospital to hospital, eventually returning to California to get much the same treatment. It was years after filming began that Edie was again available to finish the film. Her fall was no ordinary one. She was all alone in her own personal world. The Warhol Factory, with which Edie had been associated, was kind of a ward for talented but unstable personalities. Warhol took in an array of people, then used them in his artistic endeavors while providing those people opportunities to establish themselves. Edie was cast from that shelter after a while. Warhol once remarked on that topic that he thought Edie didn’t want to change her self-destructive ways. In any case, the soaring heights she reached lead to a long fall, eventually ending a life urged on by what it was seemingly missing something from the start.

Edie’s life questioned emptiness. She seemed to want to find a new life beyond herself by destroying her old one. Her methods were extreme and violent but also affecting and, in a strange way, effective on whomever they reached. The lawyer in Albert Camus’ The Fall engaged in “debauchery, a substitute for love, which quiets the laughter, restores silence, and above all, confers immortality.” But more than a mere escapist substitute, Edie’s ways seemed to have purpose. Antonin Artaud, in his life, took up the task of the “general devaluation of values.” What remains of values in Edie’s story? She left no value in illusions. Maybe Edie found at hand only cheap and superficial emotions, but she seems to know and lament that fact. At least on film this seems the case.

Palmer and Weisman were part of a splinter faction of the Warhol Factory crowd. Edie herself was sort-of cast off by Warhol. So Ciao! Manhattan looks back inside that scene from the outside. As a splinter faction, Palmer & Weisman moved away from true underground filmmaking as they distanced themselves from the Warhol crowd. In a sense, they abandon the Warhol underground filmmaking style. In The Andy Warhol Diaries, Warhol comments, “I’ve hated David Weisman ever since Ciao! Manhattan.”

Rambling along, this film finds purpose only as it keeps moving. The line between documentary and fiction is blurry. It was like finding manipulations of reality and then finding a way to recreate and capture some of those manipulations.

Cio! Manhattan took many risks with experimental techniques in order to pull the film together. A voyeuristic billionaire drug baron Mr. Verdecchio (Jean Margouleff) looks on through an elaborate video surveillance system. Having the characters separated but still linked through very artificial interaction forms perhaps the only continuous thread through the film. At the time the film was made, however, there was no such thing as video like we know today. When the filmmakers show multiple television screens showing different images, much like Abel Gance’s polyvision, this was before the technology for such things was actually available. This even predates related techniques used in Godard & Miéville’s Numero Deux.

Those portions in black & white are quite beautiful. The people seem pristine and untouched. Edie seems the epitome of grace. The color segments have different, though still distinguished, good looks. These color portions were filmed after Edie’s period of multiple hospitalizations, and she is more of a ravaged beauty. Still stunning and graceful, she seems to carry more burdens, more weight (not the least of which were her breast implants, shown off through most of the film). What brought about that ravaged state is a difficult question. Though partially answering that is the fact that the drugs Geoffrey (Geoff Briggs) brings out on a tray were Edie’s actual prescriptions. In their commentary, the filmmakers make a point to say Edie was a willing participant in the film rather than a forced victim of exploitation. Of course, it is still debatable whether Edie’s vulnerable willingness to self-destruct was precisely what was exploited.

Only one professional actor was in the cast, Isabel Jewell. This allowed the film to overflow with startling cameos from a few of the most interesting personalities of Sixties underground culture. Guru Bhavananda (a/k/a Charlie Bacis) portrays real-life preventative medicine “vitamin doctor” Dr. Robert, about whom John Lennon wrote a song for The Beatles’ Revolver. Viva (a/k/a Susan Hoffman) plays Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. Tom Flye, the drummer from the theremin-oriented band Lothar and the Hand People, is present as Mr. Verdecchio’s driver. Brigid Berlin appears as Brigid Polk. Brigid, after perfecting an Edie impersonation, also did many of Edie’s voice-overs after Edie’s death. Also appearing are Uma Thurman’s lovely mother Nena and a sometimes-naked Allen Ginsberg.

On the DVD of the film are some great little interviews — none too long but all still varied and interesting. These include costume designer Betsey Johnson, from the boutique Paraphernalia, as well as Wesley Hayes, George Plimpton, and Weisman. The DVD also has a still gallery and selected black & white outtakes that showcase some nice footage not in the film. The feature commentary track is interesting and, along with the interviews, helps sort out the action in the film via the back story on the people and places who inspired and contributed to the film.

Ciao! Manhattan is not a definitive film in any way. It presents varied, ambiguous insight. That is precisely its strength. It wanders from the Silver Sixties to the aftermath of that era. Along the way, the film is a postmodern dream of people trying to find the means to hold on to something real. But what is real? Watching the film it’s impossible to eliminate all the distance that separates us from Edie. We can only get as close as Mr. Verdecchio and look in from outside. Maybe in that respect this film is a distinctly postmodern biopic.

So here’s to you Edie, for not being immortal but still trying to go on making your great mistakes indefinitely.