For decades, “zombies” have preoccupied the makers of films, television shows, comics, and more. What does this genre have to offer? As we’ll see, there is some excellent filmmaking hidden in this genre, though many attempts to extend it are terrifyingly bad.

The earliest zombie films–White Zombie (1932), etc.–were basically typical monster movies, not terribly unlike Frankenstein (1931), or maybe thrillers–like I Walked With a Zombie (1943) that draws on myths of Hatian voodoo. Some of those movies are well regarded, but the “zombie” element was generally confined to a single character with some makeup that converted him into a monstrous “other” that the protagonist has to confront and cope with.

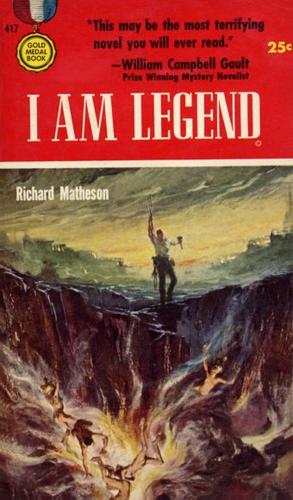

A book, I Am Legend (1954) by Robert Matheson, had a significant impact on the future use of zombies in film. As of this writing, three film adaptations have been made: The Last Man on Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) starring Charlton Heston, and I Am Legend (2007) starring Will Smith. While the book and the first movie adaptation relied on vampires rather than zombies, the story structure of having a revolutionary actor (searching for a cure) within an apocalypse of monsters would influence an unknown, independent filmmaker named George A. Romero to run with the idea in a slightly different direction. The latter two film version tended more toward the use of “zombies” than “vampires”, to some degree at least. Omega Man is probably the one to watch among them.

This idea of substituting zombies for vampires even shows up in the spirits industry, with the brewery Clown Shoes changing the name of its American Imperial Stout beer from “Vampire Slayer” to “Undead Party Crasher” after a patent and trademark attorney who co-owned a competing business distributing an imported “Vampire Pale Ale” brought a trademark infringement lawsuit. The new label for the Clown Shoes brew asks if we need the undead and trademark attorneys too. A werewolf-looking trademark attorney is having a stake driven through his heart in a cartoon in the background.

Let’s get back to cinema though. The identifiable genre of zombie films–that of the “zombie apocalypse” movie if you will–came into being with George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). Romero established himself as the undisputed master to the genre. He made B-movies like director Samuel Fuller or even John Cassavetes, making due with smaller budgets, unadorned camera and editing technique, and minimal technical features like special effects, but packing quite a punch in terms of substantive content. He delivered “soft” science fiction, in which the suspension of disbelief in re-animated corpses is a tool to explore human relations and the human condition. But unlike sci-fi films that may have explored similar human issues, zombies presented a rather simple premise that required only a minimal (if central) suspension of disbelief. There may be zombies, but all else is “normal” in the world. Romero’s films laid out the basic elements of most zombie films to follow: the “undead” (ghouls) coming back to life for unexplained reasons, slow and staggering movement, the need to destroy the head to incapacitate them, herds or swarms of them moving together, and a taste for human flesh. Where the early “monster movie” zombie pictures tended to deal with a main character’s terror of the unknown, or perhaps to suggest that monsters may just want to be like “us”, Romero flipped the relationship and suggested instead that maybe “we” are like zombies. Night of the Living Dead had an existential edge like Sartre’s play No Exit (1944), with its famous assertion that “hell is – other people.” In all of Romero’s later zombie films, though, existentialism was replaced or augmented by questions of consumerism, class consciousness, political (in)equality, and similar social commentary.

Night of the Living Dead established the frequent zombie moving setting of a sudden onset of people turning into zombies, and a group barricading themselves into a house to survive. The threat of zombies infecting others in amass outbreak explains itself easily, lending an air of credibility to an otherwise incredible plot device. Like almost all of Romero’s zombie films, the actors are basically unknown to screen audiences. He also casts the lead as an African-American, at a time when Hollywood did not do so. Most characteristic is that Romero portrays U.S.-Soviet Cold War militarism and social authority as the “real monster”. This placed Romero among the 1960s counterculture, and vaguely attached him to the so-called New Left. Though he remained an independent force, both literally in the sense of existing outside the Hollywood system, but also symbolically int he ideas presented on film.

Night of the Living Dead established the frequent zombie moving setting of a sudden onset of people turning into zombies, and a group barricading themselves into a house to survive. The threat of zombies infecting others in amass outbreak explains itself easily, lending an air of credibility to an otherwise incredible plot device. Like almost all of Romero’s zombie films, the actors are basically unknown to screen audiences. He also casts the lead as an African-American, at a time when Hollywood did not do so. Most characteristic is that Romero portrays U.S.-Soviet Cold War militarism and social authority as the “real monster”. This placed Romero among the 1960s counterculture, and vaguely attached him to the so-called New Left. Though he remained an independent force, both literally in the sense of existing outside the Hollywood system, but also symbolically int he ideas presented on film.

There were many subsequent films Romero made in the same milieu as the original Night of the Living Dead. The first was Dawn of the Dead (1978). To many, and despite rather poor acting, Dawn is the greatest of Romero’s zombie films. Rather than retreating to an isolated home, in this instalment the main characters barricade themselves inside a large shopping mall. The film addresses a legitimate question of realism: what if the government or other people cannot (or simply do not) suppress the rise of the zombies? What happens over a longer time period? Of course, people need food and other supplies. A shopping mall as a mecca of consumerism in the late 1970s is a metanym of consumer culture of the day. Romero’s biggest achievement is to show the zombies taking on “human” qualities, like trying to go to the mall and mindlessly “shop”. Unlike the early zombie films, this did not posit that zombies wanted to be like us but that consumerism has become so ingrained in Western culture that not even death and reanimation as zombies diminishes those impulses. In the 2013 documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek describes the 2011 riots in Great Britain in terms of the inability of the rioters to transcend the predominant ideology of their society, and therefore they act out within that paradigm. Romero’s mall-bound zombies are a very cynical illustration of the same point. What also becomes a trend here is the question of collective action. The onslaught of zombies seems to force the survivors to work together, overcoming whatever objections they have to doing so. In that, a subtle point is made. Working together is more effective that working alone (or against each other). The question is how this can be achieved, and maintained. King Vidor had already made Our Daily Bread (1934), about people founding a collective subsistence farm during the Great Depression, but a zombie apocalypse provides the basis to illustrate the concept more obliquely.

Day of the Dead (1985) seemed, for at time at least, to be Romero’s conclusion of a zombie trilogy. Compared to the first two films, it balances somewhat more refined and modern film technique with more nuanced social commentary. In this version the zombie apocalypse is well underway. A band of survivors holds up in a military installation whilst a resident scientist conducts research on zombies that are (with great effort and risk to humans handling them) corralled into a pen prior to the experiments. The film’s greatest strength lies in the characters. The conflict between the humans and the zombies is merely the setting to explore the tensions between the humans, with class and almost tribal characteristics dividing many of them. Soldiers resent the educated scientist’s pursuits. The civilians and pilots fear the raw aggression and violence of the soldiers. Men despise powerful women. Those in a hierarchy abhor democracy. Another key plot point must be mentioned: Bub. The scientist at the military facility is experimenting to see if the zombies can be controlled and peaceably integrated into human society. Bub (Sherman Howard) is his most promising zombie research subject. While many deride the Bub character (as something like a precursor to Jar Jar Binks of the Star Wars franchise), he represents something completely new for the genre. This is Romero’s lionization of attempts to normalize the most monstrous. It encapsulates the utopian heart of his films. Bub symbolizes a hope and belief that social transformations are possible. He presents an ideology that comes from the zombies. But there is another strikingly radical aspect to Bub as well. He also represents, just oh so slightly, a kind of core goodness of the ordinary man. While most human survivors (especially the soldiers) want the zombies exterminated, Bub is a test case for overcoming the urge to destroy what is different. The interpersonal relations of the characters who are trying in varying degrees to come to terms with these ideas is the axis on which the film turns. Bub may not be a particularly subtle device, but the reactions of the humans around him certainly are. For these reasons, Day of the Dead may be Romero’s very best.

Day of the Dead (1985) seemed, for at time at least, to be Romero’s conclusion of a zombie trilogy. Compared to the first two films, it balances somewhat more refined and modern film technique with more nuanced social commentary. In this version the zombie apocalypse is well underway. A band of survivors holds up in a military installation whilst a resident scientist conducts research on zombies that are (with great effort and risk to humans handling them) corralled into a pen prior to the experiments. The film’s greatest strength lies in the characters. The conflict between the humans and the zombies is merely the setting to explore the tensions between the humans, with class and almost tribal characteristics dividing many of them. Soldiers resent the educated scientist’s pursuits. The civilians and pilots fear the raw aggression and violence of the soldiers. Men despise powerful women. Those in a hierarchy abhor democracy. Another key plot point must be mentioned: Bub. The scientist at the military facility is experimenting to see if the zombies can be controlled and peaceably integrated into human society. Bub (Sherman Howard) is his most promising zombie research subject. While many deride the Bub character (as something like a precursor to Jar Jar Binks of the Star Wars franchise), he represents something completely new for the genre. This is Romero’s lionization of attempts to normalize the most monstrous. It encapsulates the utopian heart of his films. Bub symbolizes a hope and belief that social transformations are possible. He presents an ideology that comes from the zombies. But there is another strikingly radical aspect to Bub as well. He also represents, just oh so slightly, a kind of core goodness of the ordinary man. While most human survivors (especially the soldiers) want the zombies exterminated, Bub is a test case for overcoming the urge to destroy what is different. The interpersonal relations of the characters who are trying in varying degrees to come to terms with these ideas is the axis on which the film turns. Bub may not be a particularly subtle device, but the reactions of the humans around him certainly are. For these reasons, Day of the Dead may be Romero’s very best.

After a two decade hiatus, Romero came back with three more zombie films: Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007), and Survival of the Dead (2009). All three exhibit more self-awareness of their place in the pantheon of zombie films and use humor more liberally than the earlier Romero efforts. They also update the context by many years, in that like all of Romero’s zombie films they have a contemporary setting.

Diary of the Dead revolves around a group of college students trying to escape and survive from the time that the zombie apocalypse just begins. One of them is an aspiring filmmaker, and he is making a documentary “Diary of the Dead” to document the apocalypse to counter the false information spread by the mass media, who, on the zombie question, are trying to conceal the nature, extent and origins of the zombie outbreak. Diary‘s use of first person camera and the importance it places on alternative media are somewhat forced. The script never convincingly explains how Internet distribution of a guerrilla documentary film would really work, given that it depends on enough of humanity surviving to maintain not just internet communication lines but also electricity. The use of first person camera to draw in viewers and elicit sympathetic reactions can at times feel like a con job. Frankly, The Blair Witch Project (1999) beat Romero to the idea, which is better suited to zombies as mysterious monsters lurking in the shadows, used for fright (like an old Jacques Tourneur film) but nothing more.

Survival of the Dead picks up from a minor plot point in Diary in which a small band of soldiers rob the students. The film revolves around the questions of allegiances and trust, and the interactions not just of individuals but between small groups. The soldiers from Diary seemed like self-interested rogues in that earlier film, but in the latter are redeemed as altruistic and simply in search of survival. They eventually encounter bands of other survivors engaged in the vestiges of a kind of family feud on an island. People who seem trustworthy turn out to be con artists, and others show compassion when it counts. Intended, perhaps, as the most humane of the Romero films, the sometimes low-rent acting, not to mention the less-developed script, doesn’t always allow the surprise twists in the behavior of the characters to seem convincing. Survival seems like the least original of all of Romero’s zombie films because the major themes and interactions between characters are fairly familiar ones. No new perspectives are really made possible by their use in a zombie film. You can find much of this stuff in plenty of old westerns, for instance, and the westerns are better.

This leaves us with Land of the Dead. It is the only of Romero’s zombie films to feature A-list Hollywood actors (Dennis Hopper, John Leguizamo, Simon Baker, Asia Argento, and even Simon Pegg in a cameo). Of the “comeback” Romero films, this is easily the best. The zombie apocalypse has been underway for some extended period of time when the film opens. A group of people use a train-like armored vehicle called “Dead Reckoning” to go out into zombie-infested areas and collect supplies for a gated island city where humans have gathered. The city was a luxury condo/apartment highrise complex, and Kaufman (Dennis Hopper) is a man who has set himself up as the sort of CEO dictator of the facility. He provides amenities such that the rich who live in the highrise maintain their posh standard of living as if there was no zombie apocalypse outside. The rest of the residents of the island are either servants for Kaufman’s city-state empire, or are confined to make due in a ghetto on the streets of the island outside the main building. The main characters have varying degrees of awareness–for some, there are awakenings that play out onscreen–of what Kaufman is up to and the cruel mechanisms he employs to maintain the very divided and unequal society on the island. Many of the main characters take personal risks in order to act with altruism. And there is constant talk of how to topple Kaufman’s empire to foster equality and fairness, balanced against concern for the collateral effects that a revolution presents. In a sort of echo of the Bub character from Day of the Dead, Big Daddy (Eugene Clark) is a zombie who somehow intuitively knows how to use the remnants of human society for his own purposes. He does not need a scientists to teach him how to do these things. He appears initially at a gas station, and clumsily finds a way to use the gas pumps. He teaches other zombies, in a way, how to use other tools from the human world. As the movie progresses, Big Daddy seems to be on a mission to avenge wrongs committed by the humans against zombies. Much like Yertle, the turtle on the bottom of a king turtle’s tower built of his own turtle subjects in the Dr. Seuss story “Yertle the Turtle” (1958), who says, “we too should have rights,” Big Daddy seems to be presenting the question of whether zombies have rights too. One of the main human characters ceases fire around Big Daddy, as if to entertain the notion. The class warfare and inequality of the island city give Land of the Dead much of the same spirit as the earlier Romero movies, even if it also makes overtures to more conventionally polished Hollywood filmmaking technique. It has the hallmarks of the early Romero zombie classics, and almost like the Nineteenth Century French novelist Balzac, it uses the genre to paint a picture of human society through an assortment of specific interactions of individuals. The zombies merely provide a shock to the social structure, and empower (or force) the characters to make their own moral decisions in a relative vacuum of social ritual. Do they recreate what was before or try something else? Rather than expounding pure theory, Romero provides little set pieces for the characters to make discrete choices. What makes Romero so unique is that he uses zombie films to show character interactions that place radical options on the table–the sorts of options that are normally omitted through all sorts of ploys like concision, viability, naivety, and the like. An interesting issue not really addressed by the film is why so many of the characters seem so interested in U.S. currency. Would people really still honor it? That’s probably a question for the proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Anyway, the only quibble with the film is that Simon Baker seems miscast in the lead role. He’s a bit too affable.

This leaves us with Land of the Dead. It is the only of Romero’s zombie films to feature A-list Hollywood actors (Dennis Hopper, John Leguizamo, Simon Baker, Asia Argento, and even Simon Pegg in a cameo). Of the “comeback” Romero films, this is easily the best. The zombie apocalypse has been underway for some extended period of time when the film opens. A group of people use a train-like armored vehicle called “Dead Reckoning” to go out into zombie-infested areas and collect supplies for a gated island city where humans have gathered. The city was a luxury condo/apartment highrise complex, and Kaufman (Dennis Hopper) is a man who has set himself up as the sort of CEO dictator of the facility. He provides amenities such that the rich who live in the highrise maintain their posh standard of living as if there was no zombie apocalypse outside. The rest of the residents of the island are either servants for Kaufman’s city-state empire, or are confined to make due in a ghetto on the streets of the island outside the main building. The main characters have varying degrees of awareness–for some, there are awakenings that play out onscreen–of what Kaufman is up to and the cruel mechanisms he employs to maintain the very divided and unequal society on the island. Many of the main characters take personal risks in order to act with altruism. And there is constant talk of how to topple Kaufman’s empire to foster equality and fairness, balanced against concern for the collateral effects that a revolution presents. In a sort of echo of the Bub character from Day of the Dead, Big Daddy (Eugene Clark) is a zombie who somehow intuitively knows how to use the remnants of human society for his own purposes. He does not need a scientists to teach him how to do these things. He appears initially at a gas station, and clumsily finds a way to use the gas pumps. He teaches other zombies, in a way, how to use other tools from the human world. As the movie progresses, Big Daddy seems to be on a mission to avenge wrongs committed by the humans against zombies. Much like Yertle, the turtle on the bottom of a king turtle’s tower built of his own turtle subjects in the Dr. Seuss story “Yertle the Turtle” (1958), who says, “we too should have rights,” Big Daddy seems to be presenting the question of whether zombies have rights too. One of the main human characters ceases fire around Big Daddy, as if to entertain the notion. The class warfare and inequality of the island city give Land of the Dead much of the same spirit as the earlier Romero movies, even if it also makes overtures to more conventionally polished Hollywood filmmaking technique. It has the hallmarks of the early Romero zombie classics, and almost like the Nineteenth Century French novelist Balzac, it uses the genre to paint a picture of human society through an assortment of specific interactions of individuals. The zombies merely provide a shock to the social structure, and empower (or force) the characters to make their own moral decisions in a relative vacuum of social ritual. Do they recreate what was before or try something else? Rather than expounding pure theory, Romero provides little set pieces for the characters to make discrete choices. What makes Romero so unique is that he uses zombie films to show character interactions that place radical options on the table–the sorts of options that are normally omitted through all sorts of ploys like concision, viability, naivety, and the like. An interesting issue not really addressed by the film is why so many of the characters seem so interested in U.S. currency. Would people really still honor it? That’s probably a question for the proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Anyway, the only quibble with the film is that Simon Baker seems miscast in the lead role. He’s a bit too affable.

What about zombie movies outside the Romero universe? There have been many. Some are actually comedies. Return of the Living Dead (1985) (and its many sequels) fit the description as comedies. These films popularized the now-ubiquitous concept of zombies eating people’s brains, not just other parts of them. And because they were made with assistance from John A. Russo (the co-writer of Night of the Living Dead), they follow much of the basic Romero template for zombie behavior. Another comedic portrayal of the standard zombie apocalypse theme was Zombieland (2009). Unlike most zombie films, this was a big-budget Hollywood film. It manages to have some good gags, while trying hard to appeal to a sort of cynical nerd audience, though also dragging in a romantic subplot that could be borrowed from almost any other genre (which should be happy to be rid of it). But Shaun of the Dead (2004) is the reigning champ of zombie comedies. It is a satire of all the zombie apocalypse movies. Much of the cast of the British sitcom Spaced (1999-2001) appears in one form or another–those actors would go on to make a series of satires of different film genres together. The gags hit the right notes. They capture much of what the original Romero movies were about, with witty dialog and excellent performances. The characters make all the dumb mistakes characters always make in these movies. The send-up is self-aware and well-informed.

What about zombie movies outside the Romero universe? There have been many. Some are actually comedies. Return of the Living Dead (1985) (and its many sequels) fit the description as comedies. These films popularized the now-ubiquitous concept of zombies eating people’s brains, not just other parts of them. And because they were made with assistance from John A. Russo (the co-writer of Night of the Living Dead), they follow much of the basic Romero template for zombie behavior. Another comedic portrayal of the standard zombie apocalypse theme was Zombieland (2009). Unlike most zombie films, this was a big-budget Hollywood film. It manages to have some good gags, while trying hard to appeal to a sort of cynical nerd audience, though also dragging in a romantic subplot that could be borrowed from almost any other genre (which should be happy to be rid of it). But Shaun of the Dead (2004) is the reigning champ of zombie comedies. It is a satire of all the zombie apocalypse movies. Much of the cast of the British sitcom Spaced (1999-2001) appears in one form or another–those actors would go on to make a series of satires of different film genres together. The gags hit the right notes. They capture much of what the original Romero movies were about, with witty dialog and excellent performances. The characters make all the dumb mistakes characters always make in these movies. The send-up is self-aware and well-informed.

The most significant film to break from the Romero mold while still presenting a classic “zombie apocalypse” theme was 28 Days Later (2002). In this format, the cause of the zombie outbreak is known and explained from the very beginning of the film. Scientists are conducting biotech experiments that produce uncontrollable rage in test chimps. Animal rights activists trying to liberate the caged animals inadvertently release the disease into the human population. The infected are not the slow, lumping zombies of the Romero movies. The disease causes violent, uncontrolled imperatives to attack living humans. These zombies move quickly, always at a full run. They are almost rabid. The main character somehow survived the onset of the zombie apocalypse while in a coma in a hospital. He awakens 28 days after the outbreak, hence the title (though inexplicably he awakens in an empty hospital on clean sheets). He meets up with some other survivors who know how to navigate the apocalypse, as best as they can, and who understand–and explain and illustrate–that any contact with fluids from the zombies or any bites mean infection. The rest of the film deals with the group of survivors trying to find a military outpost that will protect them from the zombies, and the valor of individuals in the group protecting the others from both zombies and predatory humans alike. The action is taut–this is as much a pure action film as a thriller. The characters are believable and compelling. There is a clear line drawn between good and evil. Above all, though, this film set out a new set of rules for the zombies in zombie films. A sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007) was dreadful. Following the I Am Legend format there is a search for a cure, together with the now typical device of a quarantined city. Filled with main characters who are (contrary to intent) manifestly unsympathetic, the film basically imploded onto itself and can’t end soon enough.

The most significant film to break from the Romero mold while still presenting a classic “zombie apocalypse” theme was 28 Days Later (2002). In this format, the cause of the zombie outbreak is known and explained from the very beginning of the film. Scientists are conducting biotech experiments that produce uncontrollable rage in test chimps. Animal rights activists trying to liberate the caged animals inadvertently release the disease into the human population. The infected are not the slow, lumping zombies of the Romero movies. The disease causes violent, uncontrolled imperatives to attack living humans. These zombies move quickly, always at a full run. They are almost rabid. The main character somehow survived the onset of the zombie apocalypse while in a coma in a hospital. He awakens 28 days after the outbreak, hence the title (though inexplicably he awakens in an empty hospital on clean sheets). He meets up with some other survivors who know how to navigate the apocalypse, as best as they can, and who understand–and explain and illustrate–that any contact with fluids from the zombies or any bites mean infection. The rest of the film deals with the group of survivors trying to find a military outpost that will protect them from the zombies, and the valor of individuals in the group protecting the others from both zombies and predatory humans alike. The action is taut–this is as much a pure action film as a thriller. The characters are believable and compelling. There is a clear line drawn between good and evil. Above all, though, this film set out a new set of rules for the zombies in zombie films. A sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007) was dreadful. Following the I Am Legend format there is a search for a cure, together with the now typical device of a quarantined city. Filled with main characters who are (contrary to intent) manifestly unsympathetic, the film basically imploded onto itself and can’t end soon enough.

The Walking Dead (2010- ) was a surprise hit zombie apocalypse TV show, based on a graphic novel series of the same name launched in 2004 by Robert Kirkman. It is a signature cable channel show. As broadcast networks focused on cheap-to-produce reality shows, cable networks began to finance lavish dramas with production values approaching Hollywood theatrically-released movies more than standard broadcast TV fare. This won large audiences. The Walking Dead is extremely derivative of what came before it. The premise, as the series begins, is that the main character awakens from a coma to find himself in a zombie apocalypse. Sound familiar from 28 Days Later? The zombies are dubbed “walkers” (like in Romero films) and exhibit much the same lumbering movements as all the Romero films. But rather than have anything good or new to say, the show is mostly a melodrama, that is to say a soap opera. The setups are implausible. Many of the characters are inconsistent–constantly changing their personalities just to facilitate a plot twist. This show is terrible.

Hollywood has tried to catch up (and cash in) on the zombie buzz generated by the success of The Walking Dead, much like they did with a “vampire” fad a few years earlier (yet again, zombies are kind of a second wave after vampires). Among those efforts is World War Z (2013). This is a formulaic Hollywood movie through and through. The main character (Brad Pitt) searches for a cause of the epidemic, and also for a cure. Every part of the plot follows the “Chekhov’s gun” principle; foreshadowing is absolute and rigid. The zombies follow the 28 Days Later pattern of being wild and frenzied. Framing of the action borrows heavily from the disaster movie genre. The audience is expected to sympathize with the exceptionalism of the family at the center of the story, and multiple deus ex machina plot twists are needed to keep the story moving. While lavishly produced, with every technical detail nearly impeccable, the story is stupid, derivative and implausible. At least Hollywood’s last big (non-comedy) zombie movie, the Will Smith version of I Am Legend, required you to suspend disbelief only as to the presence of zombies but not with regard to the actions and emotions of the uninfected human characters. No such luck here. No, here we get a character on UN-coordinated missions who brings a satellite phone for personal communication only, making no attempt to communicate with the UN regarding his progress other than to fly around the world trying to reach their base and maybe fill them in at that point. Too bad he did not put the UN on speed dial before he left!

Wholly aside from the movies, “zombie walks,” “zombie pub crawls,” and other such events have arisen with participants donning zombie costumes and makeup. Some of these are just middle class past times. But some take up the spirit of the Romero movies by being used a protests against consumer culture, or other things. In Minneapolis on July 22, 2006 a group dressed up as zombies and lurched through a public festival, with portable audio equipment playing announcements like “get your brains here” and “brain cleanup in Aisle 5.” The police arrested them, claiming at first that it was for “disorderly conduct” but then later saying that use of the audio equipment constituted the illegal display of simulated weapons of mass destruction (“WMDs”) (yes, the police, and later city attorneys, actually asserted this). The “zombies” later won a lawsuit against the police, the court saying there was no probable cause to arrest them.

There is certainly more to the zombie phenomenon than meets the eye. For one, there are more zombie films than can be mentioned here. I didn’t even mention Bruce Campbell movies! But the pervasiveness of zombies in popular culture makes them worthy of note. Hopefully, this little primer offers a head start.

Day of the Dead

Day of the Dead