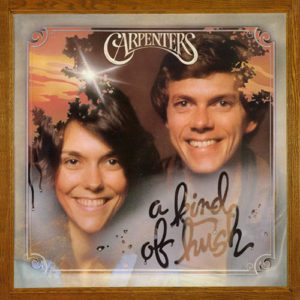

Carpenters – A Kind of Hush A&M SP 4581 (1976)

A Kind of Hush was a bit of a lesser album from The Carpenters after a string of impressive ones in the early 1970s. Of course, Karen still sings beautifully, and there are some good songs here (“Can’t Smile Without You,” “I Need to Be in Love”). But the brother-sister duo seems to struggle to find enough suitable songs to fill the album, and Richard as the producer / arranger drifts into rigid formula, not living up to his best work. He later admitted that this was a disappointing album, noting the poor song selection, and blamed it on his addition to sleeping pills at the time. Celebrity was definitely beginning to take its toll. For their next album, they tried to seek a different producer but had difficulty finding someone “major” willing, at which point Richard produced but made an effort to move out of his comfort zone. Anyway, with all seriousness, the producer (or co-producer) that the duo should have used was Tiny Tim — think about it, this makes perfect sense when The Carpenters were recording pop songs from bygone eras like “Goofus” but also in that Tiny Tim would have added a sense of modern irony that would have reinvigorated The Carpenters’ sound at a time when their old approach maybe seemed less relevant.

“In an old joke from the defunct German Democratic Republic, a German worker gets a job in Siberia; aware of how all mail will be read by the censors, he tells his friends: ‘Let’s establish a code: if a letter you get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, it’s true; if it’s written in red ink, it’s false.’ After a month, his friends get the first letter, written in blue ink: ‘Everything is wonderful here: the shops are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, cinemas show films from the West, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair — the only thing you can’t get is red ink.’ ***

“we ‘feel free’ because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom.” Slavoj Žižek, Welcome to the Desert of the Real! pp. 1-2.

At their best, The Carpenters were able to articulate the claustrophobic unfreedom of the (white) “American Dream” in the post-WWI “Golden Age”, presenting songs in “red” ink” or pointing out a lack of “red ink”. There is only a trace of that ability on A Kind of Hush. At a time when punk was making overt attacks on society, disco was celebrating individual hedonism and even hip-hop was rising from the underground, The Carpenters seemed somewhat out of touch, merely responding to conditions that many people already relegated to the past. Oh, and the album cover is indeed one of the strangest and creepiest on a major commercial release at the time. The duo’s next album Passage would be a small improvement, flirting with disco and showtunes a bit, though still prone to a few (easily avoidable) missteps.