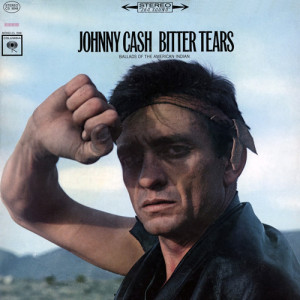

Johnny Cash – Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian Columbia CS 9048 (1964)

Behind a lot of Johnny Cash’s work lies a firm belief in egalitarianism, the idea that every person has inherent worth and should be treated fairly and equally. To the extent that he recorded a lot of “patriotic” music it might be said that it was partly because he viewed egalitarianism as part of a core national identity. There is no better example of Cash’s commitment to egalitarianism and social justice than Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian.

The theme of the album is the treatment of native Americans (“American indians” would have been considered the most respectful term at the time). Songs cover topics like treaties (specifically, the Treaty of Canandaigua) between the government of European settlers and native nations in the context of recent breaches by President Kennedy (“As Long as the Grass Shall Grow”), the creation of a written language of the Cherokee by Sequoyah (“Talking Leaves”), the military service and tragic death of Ira Hayes (“The Ballad of Ira Hayes”), and a humorous jab at the crushing defeat of an invading U.S. government military force led by George Armstrong Custer by allied Native tribes at the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876 (“Custer”). It was highly unusual for celebrities to highlight native American issues in 1964, though the Freedom Movement or Civil Rights Movement focusing mostly on African-Americans was still underway.

Cash worked closely with Peter La Farge on the album, who wrote five of the eight songs but does not appear on the recordings. La Farge was a fixture of the Greenwich Village folk scene in the early 1960s. He was a performer of very limited means, but Cash liked him personally.

The musical tone of the album is similar to Cash’s other early 60s albums, with rather minimal instrumentation in a folk-like setting. He tends toward a very respectful approach to the music, making the topics seem dignified and important. But the subject matter puts this more in a class with protest albums like Dylan‘s The Times They Are A-Changin‘ from the same year than anything coming out of Nashville at the time.

Bitter Tears is somewhat divisive among fans. For some, it represents the epitome of Cash’s integrity, a testament to his image as something of a crusader for noble causes. To others, this is a contrived, heavy-handed political statement lacking in purely musical merits. For me, it’s some of Cash’s most admirable work, maybe a little uneven, but with a passion and significance matched with the simple folk stylings that were effective and endearing.