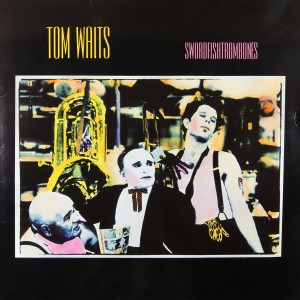

James Hoopes – False Prophets: The Gurus Who Created Modern Management and Why Their Ideas Are Bad for Business Today (Perseus Publishing 2003)

James Hoopes is a historian who has written numerous books on business management. One of his best-known books is False Prophets, which covers the American phenomenon of “business management gurus” that started at the turn of the 20th Century and has continued to the present.

This is really two different projects merged into one. First and foremost, it is a series of biographical sketches of the key business management gurus of American history and their careers. This part of the book is much like George Soule‘s Ideas of the Great Economists (1952), etc. It provides a handy, very readable introduction to how the various business management gurus rose to prominence advocating particular theories, and the personal circumstances of the gurus themselves. On the other hand, this book also reads like a series of “reviews” (i.e., critiques) of the various business management theories advanced by those gurus. This is where Hoopes’ credibility wanes. He has a sharp, cynical wit, but he’s also prone to arrogant, unsupported generalizations and seems to really have an axe to grind, ultimately deploying a theory of the proper role of management that is both ill-defined and also outside the scope of his biographical treatments. He tries to come across as objective by adding in some form of praise and criticism for each guru chronicled in the book, but there are bigger problems with respect to the unsubstantiated foundations for this praise and criticism and in the haphazard selection of gurus addressed (or not) in the text.

Let’s first look at the real goldmine of the book: the biographical sketches. Hoopes does an admirable job discussing some historical details that are often overlooked by proponents of the management theories of the gurus he has selected for this history. What emerges, subtly, is a portrait of theorists who got ahead only when serving the interests of the powerful. So the privileged, upper-class background of Frederick Winslow Taylor — Hoopes cleverly nicknames him “the demon” — is drawn out, and it helps explain some of the tactical victories and errors in Taylor’s advocacy of his theories. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth make appearances, and Hoopes does well to explain how much of their work has been wrongly credited to Taylor. Then it is on to Mary Parker Follett. Along with Lillian Gilbreth, Follett represented a pioneering female voice in American business. Maybe more than any other business management guru she added new, substantive theories. She also had the fortune of working with liberal businessmen like Henry S. Dennison, who experimented with forms of employee stock ownership at his company. Then there is Elton Mayo. Hoopes describes him as a charlatan. That is perhaps too kind. His unscrupulous striving is portrayed well in Hoopes’ caustic narrative. The Mayo chapter is one of the best, in part because Mayo’s disciples gathered so much data that Hoopes can pick it apart and demonstrate with specificity how Mayo proffered theories that contradicted his own data. Hoopes relentlessly skewers the Harvard Business School and the gurus like Mayo who were attached to it early on. There is also an excellent chapter on Chester Barnard, where Hoopes actually digs in and debunks some of the guru’s writings and suppositions in a systematic manner. The rather desperate anti-communist views of many of the gurus comes out most strongly in the middle chapters on Mayo and Barnard, though it shows elsewhere too. Lastly we have the more modern figures, W. Edwards Deming and Peter Drucker. The history of Deming’s public service for the U.S. government before becoming a business guru presented here is welcomed, because many books about Deming omit or minimize that phase of his life. Hoopes sometimes gushes over Drucker, who, along with Follett, is clearly one of his favorites of the gurus (“on management technique, a CEO could scarcely do better than to listen to Drucker.”).

Looking across all the biographical sketches, we see that many of the gurus leveraged characteristics unrelated to management to push for adoption of their management theories. So Taylor and Frank Gilbreth each had inventions that helped give them success and notoriety that in turn allowed them to advocate what were separate management theories (often, not surprisingly, theories that they in turn used to promote adoption of their inventions, with all the associated personal gain that entailed). Taylor and Follett leveraged their upper-class upbringings to insinuate themselves with business owners.

What seems lacking in the biographical sketches, though, are detailed treatments of more recent gurus: Tom Peters, Jim Collins, Douglas McGregor, etc. Hoopes limits himself only to the gurus of the past, not the ones workers today are subjected to directly. (For treatment of the more contemporary gurus, books like Matthew Stewart‘s The Management Myth might be consulted). There is little here about what business gurus are saying for or against modern practices of periodic layoffs, financialization, outsourcing/offshoring, fissuring of responsibility, or defense mechanisms against corporate raiders.

So, let us turn to the more problematic part of Hoopes’ book, the critiques of the management gurus’ theories. Most of Hoopes’ arguments (critiques) follow the “appeal to expert authority” model. Yet, in the introduction, he states that he is not really an expert in business, he is a historian. That makes this lack of evidence all the more troubling, and sets himself up for criticism by structuring his book around a tu quoque logical fallacy. This runs deeper than just his expertise in “business” pe se. For instance, when talking about Frederick Winslow Taylor, Hoopes is compelled to rely on his own theory — democracy doesn’t work in business but you can’t be a tyrant. Hoopes beats this message across again and again (and again), with pure tautology, though he never justifies it as a legitimate starting point. The problem seems to be that Taylor’s theories seem, superficially, the closest to what Hoopes is advocating, thus he needs to argue most vociferously for (slight) distinction over the next closest theory to his own.

It might help to break down the key theses that Hoopes advances, to better pinpoint where he goes wrong. He argues that (a) Americans believe in socio-political democracy, (b) that workplaces lack such democracy, (c) that top-down workplace hierarchies produce better results than democratic organization strategies, and concludes that (d) people need to accept that top-down management power is necessary to some degree, though it is outsized in the degree advocated by the management gurus. Basically, this book sets out these theses, but it never gets around to proving (or disproving) most of them. It would be possible to make evidence-based analyses of each of these points. Hoopes does not even attempt to do so. Instead, he merely draws conclusions based on the historical anecdotes contained in his biographical sketches. This has the frustrating tendency of taking an almost reductionist, deterministic view of the world.

Suffice it to say, he does put forward enough historical information to strongly suggest that (b) workplaces have generally lacked democracy — though his history stops in the 1980s so present conditions can only be inferred. However, setting aside a few exceptions for workplaces that may try to achieve industrial democracy, Hoopes’ contention about a lack of workplace democracy is unlikely to be challenged by anyone looking at the great bulk of American corporations today. Evidence of a lack of workplace democracy abounds. But even his assertion that (a) Americans believe in socio-political democracy outside the workplace is something for which he offers vague generalizations and isolated quotations from the Founding Fathers, rather than, say, survey or opinion results, or even anything that connects the Revolutionary War era to the early 20th Century period that coincides with the biographical sketches that open the book. The way “democracy” was defined in, say, ancient Athens, was not the same as what Jean-Jacques Rousseau put forward during the Enlightenment. And the American Founding Fathers mostly just adopted political philosophies from Europe. Anyway, might Americans’ views have changed since Thomas Jefferson‘s time? Certainly, they have, but this book does not really point to anything to contextualize or empirically support its assertions in this regard. Hoopes doesn’t come across very invested in democracy, revealing his rather elitist/aristocratic stripes as he avoids any contemporary context for his occasional references to democracy. Though on the other hand he could have merely overstepped his area of expertise, and made some inept characterizations purely by accident due to unfamiliarity with political philosophy.

If we turn to Hoopes’ other contentions, it becomes clear that he is actually covering ground already traversed by scholars. For instance, the sociologist C. Wright Mills wrote a book White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951) that opened up discussions about how citizens accepted (or not) managerial control over their lives. Mills’ views have been summarized this way:

“For Mills, there are three forms of power. The first is coercion or physical force. Mills writes that such coercion is rarely needed in the modern democratic state. While such power underlies the other two, it is only used as a last resort. The second type of power Mills characterizes as ‘authority.’ This is power that is attached to positions and is justified by the beliefs of the obedient. The final form of power, Mills writes, is ‘manipulation.’ Manipulation is power that is wielded without the conscious knowledge of the powerless. While bureaucratic structures are based on authority, Mills saw such authority often shifting toward manipulation. *** As modern management becomes the reigning ethos of the age, the shift from explicit authority relationships to more subtle manipulation becomes the preferred form of power.” (The Sociology of C. Wright Mills) (internal citations omitted)

Hoopes concerns himself with similar topics. Moreover, the historian David F. Noble wrote various books about management control (America By Design, Forces of Production) that seem to vaguely fit Hoopes’ analysis, yet ultimately reject Hoopes’ conclusion that workplace democracy is inefficient and that top-down power must be accepted. It is here that the lack of evidence in Hoopes’ narrative becomes problematic — very problematic. For instance, Hoopes at one point argues that bottom-up democratic control of workplaces doesn’t work based on a dubious conclusion that Herbert Hoover tried that as president and it did not avert or overcome the Great Depression. Apart from the false analogy that presumes running a business and running a republic are interchangeable concepts (Machiavelli, whom Hoopes quotes early on, would be rolling in his grave), this seems to fall into the trap of deducing a general theory from a single anecdote. Or take a scene (rather misleadingly described by Hoopes) in which Frank Gilbreth supposedly upstages the anarchist activist Emma Goldman by turning a chart showing a workplace hierarchy upside down — misleading because Gilbreth’s wife Lillian actually whispered to him to pull the stunt, but also because this was so obviously a stupid stunt without rational credibility! Hoopes credits the scene as a win for the Gilbreths but one could make a stronger argument that it was actually a win for Goldman, revealing the vacuousness of what the Gilbreths were selling. Anyway, others have considered these questions before and reached different conclusions. They have done so with more detailed analyses, and with evidence. And for that matter, aside from the condescending reference to Emma Goldman, Hoopes glosses past any leftist management thinkers out there. For instance, one of the best-selling novels of the 19th Century was Edward Bellamy‘s Looking Backward, which laid out in some detail a socialist utopian vision of military-like industrial organization. Why does that not count as a significant business management theory? Sure, it was fiction and wasn’t actually implemented, but if it was so popular that “Bellamy societies” sprung up, why should it be preemptively dismissed? Or why not feature another guru, outside the realm of fiction, as far left as Bellamy? Otto Neurath was a key thinker in this space. And Lenin wrote in 1918 that “we must raise the question of applying much of what is scientific and progressive in the Taylor system” because the “Taylor system . . . is a combination of the refined brutality of bourgeois exploitation and a number of the greatest scientific achievements in the field of analysing mechanical motions during work . . . . We must organise in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system and systematically try it out and adapt it to our own ends.” Also, in the decade before the Great Depression the prominent economist Thorstein Veblen called for a Soviet of Engineers (The Engineers and the Price System). H.L. Gantt, along with the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), advanced some of Veblen’s views, but Hoopes doesn’t really spend much time on this in his treatment of Gantt. Hoopes offers only the blunt dismissal that “clearly” a society run by engineers would be a hell. As a professor once said to me, whenever someone starts a sentence with “clearly”, everything that follows is unsupported. That professor’s advice holds in this case. Hoopes has nothing substantive to rebut the left perspectives he repeatedly derides, only platitudes. His analysis is every bit as shallow as an Ayn Rand novel.

By limiting his book to the discussion of only American management, Hoopes also misses an opportunity to add broader perspectives. This leads him, for instance, to tend to mention certain management practices that were adopted in the former Soviet Union and conclude that the mere adoption in the Soviet Union disproves their efficacy–sort of a cold war horseshoe-theory inverse of “Godwin’s law of Nazi analogies.” Yet Hoopes’ critique of the sacrifices to power that individuals make in the name of corporate profits is like a mirror image those critiques of Soviet collectivization found in Andrei Platonov‘s novel The Foundation Pit (1987). While Platonov saw socialism as a desired goal that was bungled in the Soviet Union through descent into despotic Stalinism, Hoopes sees such aims as ridiculous from the outset, and instead focuses on the technocratic bungling of business objectives in the market economy (simply presumed to be the inevitable and best system) in the hands of business gurus. So don’t expect cultural reference points outside classic liberalism here. Hoopes repeatedly makes dismissive statements about the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, and the Cold War. He is somewhat a casualty of Cold War hysteria. His treatments of certain historical events reveals this, offering absurd nationalist chauvinist explanations for the arms race (blaming the Soviets, rather than the Americans!), mapping a bizarre history of advances in industry in the Baltics (crediting the Hapsburgs rather than, say, Tito’s greater achievements), etc. It is a sad facet of many writers of his generation.

In Confronting Managerialism, Robert Locke and J-C Spender compare American-style management (and business education) to that of Germany and Japan. With just these two other data points — still a limited sample — they demolish the idea that American management represents optimal efficiency. For instance, they recommend that the United States adopt the “codeterminancy” provisions of German law, whereby rank-and-file workers are legally entitled to place a representative on a supervisory board of their firm (i.e., the Board of Directors), and supervisory boards are separated from management boards (i.e., a CEO, from a management board, cannot sit on the Board of Directors or other supervisory board). While Hoopes’ narrative focuses on a “micro” level of management power, Locke and Spender discuss an ersatz kind of “macro” power equalization used in Germany that, at least in very modest (though still woefully inadequate) ways, might theoretically counterbalance some abuses of micro-level management authority. If workers feel disadvantaged by “top-down” micro-level power exercised by managers to control daily activities, they can (potentially) exert authority from a supervisory board to remove such managers and guide long-term strategy and working conditions in another direction (assuming worker representatives are not co-opted and essentially bribed, as they often are in practice). Hoopes perhaps rightly points out that efficiency in the workplace doesn’t lead to equality in distributive rewards — though he is too quick to pronounce that equality in distributions frustrates efficiency, without data to support that assertion. Locke and Spender are somewhat naive in their own ways about these things, but it says a lot that Hoopes doesn’t discuss anything to the political left of his (arbitrary) positions. As Nancy Fraser has said, “The forces of capital insist that issues concerning the workplace should be decided by the markets, by the bosses, that these are not issues for democratic, political, collective self-determination. There’s a line between what the private owners of capital decide and what we as democratic majorities decide.” This places Hoopes among the “forces of capital”, which is not a neutral and objective position. Hoopes seeks to depoliticize these issues.

One can read Hoopes’ book and wonder whether he’s really just critiquing the tactics of neoliberal business management from the standpoint of classical liberal values, by looking to the historical pillars of business management theory that led to and still support the predominant neoliberal outlook of today. Peter Frase wrote that “neoliberalism can be seen not just as a tool to smash the institutions of the working class, but also as a mystified and dishonest representation of the workers’ own frustrated desires for freedom and autonomy.” Frase is describing in many ways the same thesis that Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello advanced in their 1999 book Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme [The New Spirit of Capitalism], which has been summarized as saying that “capitalism usurped the left’s rhetoric of worker self-management, turning it from an anti-capitalist slogan to a capitalist one.” But Hoopes launches a fairly limp retort, not really coming from the left as such. So he critiques W. Edwards Deming for not making the role of management power explicit in his pronouncements, while also commending Deming for actually making strides in many areas (coincidentally, Deming came to prominence as a “guru” in the United States as the neoliberal era came to fully dominate the economy during the Reagan administration). He also endorses “free trade” regimes, a bedrock principle of liberalism, and criticizes alternatives. Yet his endorsements of free trade omit discussion of the inequality that is generally the hidden or disavowed goal of such policies.

Ultimately, all this reveals a lot about where Hoopes is coming from, politically. He’s a sort of classical, conservative, paternalistic and aristocratic pro-capitalist liberal, in line with Peter Drucker, believing in the need for benevolent dictators in workplace management to achieve conditions that are “good” because they maintain a “proper” balance of inequalities. He takes a dim view of human nature that most people are stupid, lazy and need to be controlled by their betters — even as he occasionally criticizes others for saying the same sorts of things. One is left thinking that Hoopes laments how Americans cling to democracy (“The story of the pioneer gurus matters today because they helped to create unrealistic hopes for democracy and moral legitimacy in the workplace that continue in our time.”), as an impediment to a liberal conception of economic progress (profit growth) that is driven and sustained by noble inequalities (“The best possible act of corporate ‘social responsibility’ would be to acknowledge the conflict, and therefore help maintain the balance, between the top-down management power that has made us rich and the bottom-up political values that keep us free.”). He does not want deceptive, savage, blind and hypocritical assertions of consolidated power that render much of the population superfluous as with contemporary neoliberalism, or the thunderously brutal power of a ruthless dictator as was common in the more distant past, but he wants assertions of power nonetheless — benign or balanced power of some sort, attuned to an “optimum” value that is never adequately explained or justified in these pages but rather taken as a given. In Mills’ lexicon, he wants “authority” but not “coercion” or “manipulation”. Workers should just accept a subordinate role, apparently (“Most employees know the score and are capable of high morale in imperfect and unjust situations as long as they believe managers are honestly doing the best they can.”). Like all liberals, he pines for a capitalist world of unequal power without such inequalities causing conflict. And he calls socialists naïve! In Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität (1922), the Nazi sympathizer Carl Schmitt said, “The essence of liberalism is negotiation, a cautious half measure, in the hope that the definitive dispute, the decisive bloody battle, can be transformed into a parliamentary debate and permit the decision to be suspended forever in an everlasting discussion.” This is precisely what False Prophets advances, the endless deferral of resolution to the question of who holds power in business firms, and perhaps by extension in society at large, while emphasizing that the question should be continuously (but pointlessly) debated. Questions of how certain people or groups obtained power originally, and how others were denied, are taken off the table and depoliticized. Those things are simply bracketed out of the discussion. The status quo is miraculously maintained as long as all attention is devoted to merely identifying and discussing its character, stopping short of considering its origins. This is worth pondering, when you read Hoopes’ repeated references to the Founding Fathers of the United States, considering that the historian Charles A. Beard wrote in An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) and Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915) that they really just tried to cement their pre-existing economic privileges in a reactionary and undemocratic way — George Washington being the richest person in the nation, the fugitive slave clause a conspicuous feature of the constitution put forward by those supposedly democratic legislators, women being denied the vote, and so forth.

The part of Hoopes’ argument that is most sorely lacking in evidence is the one that says that top-down workplace hierarchies produce better results than democratic organization strategies. He states repeatedly that non-democratic management makes us rich, but who is this “us” precisely? Some might say that unequal distributions make some rich and others poor. There is, for instance, a movement for “democracy at work” that advocates directly counter to Hoopes’ thesis — and this movement has historical precedents. The most cited recent example this other contingent gives is the worker-directed cooperative Mondragon from Spain. While no doubt Mondragon is not necessarily the ultimate and perfect organization, it did survive being banned by the fascist Franco regime. There are also other examples of worker-managed enterprises. Advocates of “democracy at work” (or “economic democracy”) tend to draw distinctions between different types of worker involvement, which Hoopes does not address. But by leaving out the experiences of Spain or any other countries (e.g., Sweden) with alternate management structures, Hoopes avoids having to meaningfully confront evidence that might contradict his thesis on the (in)efficacy of democratic management. He merely dismisses these things out of hand as “idealistic” based on nothing more than a few aphorisms and snide comments. In this way he sets up false choices — its really a form of anti-communist liberal blackmail.

Where Hoopes does make a semi-convincing framing of his argument is that he tends to emphasize the sorts of factors that sociologist Pierre Bourdieu cataloged in The Social Structures of the Economy (2005). That is to say, he takes the view that business strategies are not immutable, but contingent upon certain social contexts that are usually omitted from the models that the management gurus advance. This comes close to the sociological approach that views a business firm as a field of struggle, just as there is a field of struggle between firms in the wider economy. But Hoopes is not systematic in adopting any sort of structured analysis, nor does he actually gather quantitative data like Bourdieu (or other power structure researchers, or even Phil Rosenzweig in The Halo Effect). This is the biggest disappointment of False Prophets. The idea of a critique of business management gurus is interesting, though the lack of any sort of evidence-based testing of Hoopes’ underlying theses makes the book’s claims paper thin. For what it’s worth, Hoopes seems right to emphasize how business management gurus increasingly tend to conceal the aspects of power that underlie most “management” programs (after all, the goal of ideology is to conceal its aims of domination), but he seems wrong in his conclusions that top-down management is either necessary or more efficient. It is unfortunately easy to summarily dismiss all of Hoopes’ claims in that regard, because he puts forth no evidence. That is doubly a shame because he’s also done admirable work painting short biographical sketches, from that of the egotistical tyrant Frederick W. Taylor, to the smart, indomitable Lillian Gilbreth, to the ingenious maverick H.L. Gantt, to the duplicitous strivers Elton Mayo and Chester Barnard, or to the studious civil servant W. Edwards Deming.

The chapters are ultimately uneven. The best are on Mary Parker Follett, Elton Mayo and Chester Barnard. The worst are the one on Frederick W. Taylor and the introduction, which get lost on judgmental diversions away from purely biographical material, as well as a bit of gushing hagiography in the chapter on Peter Drucker. A clear problem is that most of the weakest parts of the book are at the beginning. Hoopes doesn’t hit his stride until about mid-way through the book, before loosing his grip again at the end.

This is a book the publisher should have perhaps rejected, asking the author to remove the judgmental tone and focus on the biographical sketches alone in a more straightforward manner. Or at the least, those aspects should have been segregated out from the biographical material and minimally supported by some kind of research (preferably by the ample body of work sociologists have done on the subject). The introduction and conclusion should also have been reformulated, to bear closer resemblances to the body of the book, rather than being mostly unrelated digressions where Hoopes waxes on about his own management ideas in relation to contemporary gurus not given biographical treatments. But despite its flaws, False Prophets does pull together some useful information on a few historical figures whose ideas continue to be used to justify business practices that exert a tremendous influence on the daily lives of so many working people.