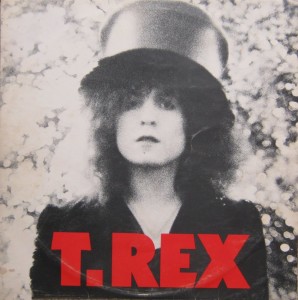

T.REX – The Slider T.Rex Wax Records BLN 5001 (1972)

The Slider is an album best understood in terms of both its contrasting and consonant elements. Marc Bolan’s almost feminine falsetto vocals and vulnerable, confessional lyrics that make the ordinary seem almost profound are set against choogling glam rock guitar riffs and big, beaty drumming. Some of the guitar is processed to sound almost like a horn section (“Rock On,” “Metal Guru” — or are those really horns?). Occasionally there are slicing guitar solos, picked out on a string or two with some tremolo and wah pedal, that are played in a style incongruous with the rest of the chorded riffs. The bass noodles around much more than the lead guitar (especially on “Mystic Lady”), rumbling along in a totally different register. These contrasts sit in odd comfort with one another. They are contrasts that nonetheless work together as building blocks of different materials. They seem like necessary elements of something much more than monochromatic bombast. But the real secret behind of The Slider is found in producer Tony Visconti‘s string arrangements.

In the 1960s, string arrangements in rock recordings were an odd thing. Often they were used for crossover appeal, drawing something from pre-rock mainstream pop and showtunes that was applied to entirely different rock songs to add ornate embellishment. Record labels frequently drafted arrangers from the pop world, or even the folk world, and had them apply their treatments to the work of artists they seemed entirely unfamiliar with. There are scores of albums like this, with the arrangers simply working from a script that bears no relation to what the featured performers are up to. Sometimes it works, even spectacularly (Sam Cooke‘s “A Change is Gonna Come,” Nico‘s Chelsea Girl), other times it is pretty hit or miss (Nina Simone on Philips, Judy Collins‘ In My Life). The best of these tended to be when arrangers took a chance on tailoring the arrangements to the performer’s quirks. Still, the more successful forays tended to involve music that wasn’t really hard rock, but rather smooth soul, urban folk, teen pop…seemingly always music without an audacious electric guitar at the forefront. A breakthrough, perhaps, was when Paul Buckmaster worked with The Rolling Stones, doing arrangements for songs like “Sway” and “Moonlight Mile” from Sticky Fingers. That was something different. Those were string arrangements that lent a dramatic, anthemic, even cinematic sheen in support of harder, darker rock music. Maybe the electric guitars weren’t up front on “Moonlight Mile” as they were on “Sway,” but Mick Jagger was still on the verge of screaming. Visconti applies this to many of the songs on The Slider. It is a stroke of genius. What normally would be a contrast with the groovy glam guitar riffs ends up being perfectly complementary support. There are other contrasts, but the strings simply extend the guitar, like the wingspan of a mighty, mythical bird that reach out from its body with majestic grace. There are no doubts, not for a second, that everything here is in support of rock music and everything it stands for.

In hindsight, it is easy to see T. Rex as a bridge between the 1950s rock ‘n roll explosion, 60s hippie counterculture and the rawness of late 1970s punk. This was music still interested in trying to change the world, holding open the possibilities that 60s idealism fostered while adding a more gender-conscious perspective and a simpler, more minimalistic kind of guitar playing.

The songs here are frequently quite good. Really, really good, that is. The title track is up there with T. Rex’s very best, a melancholy tune steeped with dreamy longing and declarations that straddle self-reflection and provocation. “Rock On” and “Telegram Sam” really drive home the nearly boogie-rock grooves the hardest. “Baby Boomerang” is an update of the rock staple “Hound Dog.” “Spaceball Ricochet” has acoustic guitar and a singer-songwriter vibe. “Metal Guru” ties the uptempo and the mellow in one package. Even the songs on the second side that might seem like filler are really quite competent and worthwhile. This is music with a flair for theatrics and drama. But, hey, it never second-guesses its own intentions in using those devices. It gives the mundane the same treatment as the profound, making the ordinary seem profound. The Slider is also good-natured to its very core. Large swaths of it have a tongue planted firmly in cheek. There are few rock albums of the early 70s as likable and durable as this one.