Link to an article by Becky O’Malley:

Month: May 2015

The Ascent by Larisa Shepitko

Link to a film review:

Marianne Faithfull – Broken English

Marianne Faithfull – Broken English Island ILPS 9570 (1979)

When rock and roll arrived in the 1950s, it was fundamentally a young person’s game. It took a while, until a generation of people who came of age after the birth rock grew up, for rock to adapt to the context of — if not middle age — at least the age when the energy, idealism and intransigence of youth wear off. So like a late 70s counterpart of Neil Young‘s Tonight’s the Night, and something of a partial precursor to Lou Reed‘s The Blue Mask, Broken English is a chronicle of trying to pull one’s self together at a time in life when there are plenty of mistakes to look back on. You could maybe even throw Magazine‘s Secondhand Daylight into that category too. There is no doubt this album sounds at least a little dated, with a tinge of the disco era lurking in the softened bass-heavy grooves. Even if it doesn’t completely succeed, this album makes attempts at opening up new territories for rock music. There is a sense of looking back and finding yourself to blame for every misstep and missed opportunity. Imagine it this way: an effervescent and up-and-coming French chanson star is giddily on her way into a recording studio, but a coughing, wheezing figure walks out — nearly staggering — from a dark corner and with a gruff voice she offers a forbidding warning about how the future will really turn out, offering the disheartening forecast in…”broken English.”

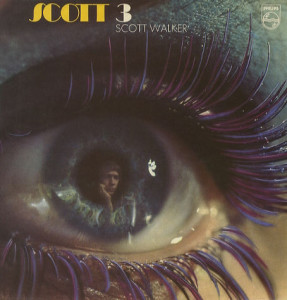

Scott Walker – Scott 3

Scott Walker – Scott 3 Philips SBL 7882 (1969)

Mr. Walker washed away every trace of duality on Scott 3. The beauty of his music comes through its resilience. Like a purple and sepia whirlwind. Fiercely strong from some inner source he taps. The primary mystery of Mr. Walker’s music is the absurdity of its context, casting Frank Sinatra or Tony Bennett as steadfast existentialists. Each grand orchestral piece finely feeds personal concerns that meander about without dogma to guide or crush them. The great achievement is the dive into the void of pop crooning. In that void is the perfect space to make something happen. Mr. Walker’s gift was perhaps the vision to find his space, that invisible blank abyss which seemed to have always been in plain view. He recognized something was possible in his space, his nothingness.

This album lives in daylight, like a vista warmed into life by the sun. It is quite a different experience from the nighttime torment of Scott 4. It is lyrically imposing. The songs are difficult to penetrate, alien to prevailing reason. Still, the detached experience of hearing Mr. Walker question prevailing reason is what makes the album such a major achievement.

Though Mr. Walker’s name always carried little cachet in his American homeland, worldwide success wouldn’t have led to Scott 3. To parrot his lyrics, “In a world filled with friends/ you lose your way.”

Noam Chomsky – U.S. Power and the Godfather Principle

Link to an interview with Noam Chomsky:

Reed Jordan – A Closer Look at Income and Race Concentration in Public Schools

Link to an article by Reed Jordan:

“A Closer Look at Income and Race Concentration in Public Schools”

Burn After Reading

Burn After Reading (2008)

Focus Features

Directors: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

Main Cast: Frances McDormand, John Malkovich, George Clooney, Tilda Swinton, Brad Pitt

Admittedly, the only Cohen Brothers movie that I’ve ever liked is The Hudsucker Proxy (1994). But I came to Burn After Reading not realizing it was a Cohen Brothers movie. Anyway, the plot here is one part expanded love triangle (akin to Sartre’s No Exit) and the other part zany spy comedy. Unsurprisingly, the characters are caricatures, and the audience is supposed to smugly view themselves above them. Each runs about chasing after an image of themselves they want others to adopt, be it Makovich’s uncompromising intellectual, Clooney’s athletic lothario, or McDormand’s youthful striver, yet they all find no one really interested (much like Jason Alexander‘s character George Costanza can’t find anyone to adopt his desired nickname “T-Bone” in an episode of TV’s Seinfeld). The film wants to be kind of like a Kafka novel, probing the emptiness of formal law and order, but it stumbles as it mocks pretty much all of the central characters. Nobody in the film ever sublimates their venal greed and desires. Brad Pitt’s character is about the only one the filmmakers can’t mock effectively, because they never really present him as having any ambitions beyond exercising and being a dope. Put this next to Orson Welles‘ Kafka adaptation of The Trial (1962) and it seems a bit weak. Sure, there is some good acting and a few funny gags. But the film sort of preys upon “simple” folks as targets for ridicule. It would be a far more subversive film if it included some of the CIA bigwigs or other peripheral yet powerful characters in the film and also held up their stupid desires and dreams for ridicule (perhaps like early Miloš Forman films). As it stands, Burn After Reading is about halfway to a good film. But only halfway.

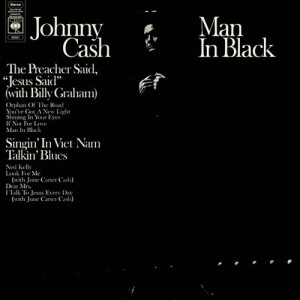

Johnny Cash – Man in Black

Johnny Cash – Man in Black Columbia 30550 (1971)

The accepted wisdom is that sometime around the 1970s Johnny Cash’s music became effete. It would be unfair to place any blame for that on Man in Black, which, aside from the still-better Ragged Old Flag, has to be one of his best offerings until the American Recordings two decades later. Here he adopted a folky, singer-songriter style reminiscent of Orange Blossom Special or Hello, I’m Johnny Cash but more stripped down. It works, and it works well. Now, let’s get one thing out of the way. The opening song “The Preacher Said, ‘Jesus Said,'” with its grating narration by Billy Graham (whom Malcolm X called a “white nationalist” and who advocated war crimes during the Vietnam War), is difficult to stomach. Cash’s “born again” christian sentiments get the better of him, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last time. If you can look past that first track, the rest is a lot more rewarding. “Orphan of the Road” is a highlight, and makes it interesting to contemplate how a collaboration with John Fahey might have sounded. Other songs like “You’ve Got A New Light Shining In Your Eyes,” with its clear and bright vocals, and “Man in Black,” with its empowered tone, are quite good too. Side two features some interesting songwriting from Cash. The beautifully honest “Singing in Vietnam Talking Blues” (sung to the same rhythm as “A Boy Named Sue”) is an autobiographical account of a USO performance for U.S. troops fighting in Viet Nam. He sings:

we did our best

to let ’em know that we care

for every last one of ’em

that’s over there

whether we belong over there or not

That last line — just sort of tossed in — is really the sort of thing that separates Johnny Cash from so many other country musicians. Reactionary populism runs pretty thick with a lot of country stars (check: Merle Haggard‘s The Fightin’ Side of Me), but few are or were willing to even imply sympathy with protest or peace movements. But Cash was always cut from a different cloth. He sang songs about the North, about Alaska and Minnesota. He also would sing songs for prisoners, like “Dear Mrs.” here. It’s hard to pin down Johnny Cash on his politics. He always dodged those issues pretty successfully, in part because he sometimes seemed to play both sides (“Ragged Old Flag” or “The One on the Right Is on the Left” anyone?). In concert he once called himself a “dove with claws.” But his ability to successfully and quite matter-of-factly broach a lot of difficult and unpopular subjects (Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian) and still maintain celebrity status was impressive.

Ernest Harsch – Resurrecting Thomas Sankara

Juan Cruz Ferre – Argentina: Workers’ Management as a Response to the Crisis

Link to an article by Juan Cruz Ferre:

“Argentina: Workers’ Management as a Response to the Crisis”