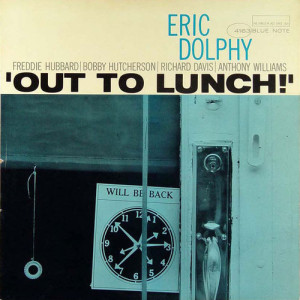

Eric Dolphy – ‘Out to Lunch!’ Blue Note BLP 4163 (1964)

For a long time, my favorite album. I know it so well. These days, I rarely ever listen to it. I carry it with me, in my head, always. So, little need for stereos. Except, the vibrations are good. So every once and a while, I take the time to play it, just to feel it.

It is hard to find words to describe this album. One can only claim to shed some light on its context. Sometimes hailed the greatest jazz recording of the 20th Century, it is certainly a key step through any legitimate jazz listening education.

Eric Dolphy was a star amidst the early “free jazz” movement of the sixties, if there was such title to bestow. He played with most of the key players at one point or another (even La Monte Young in junior high!). A California symphony denied him a seat, likely based on his race. His friend Richard Davis describes Dolphy as “an angel” and said if you heard something from Eric, it was true. His music reflected his personality. It was always reaching, but peaceful and wise.

This music arrives independently at chordal improvisation. It’s not that it begins with a structure. Rather, Dolphy rethinks his entire musical universe and then constructs his own version of what it could be. The result just happens — by chance — to sound like it employs traditional values. New concepts emerge. As much as it touches on traditional values the previous standards fail to address the full scope of this album. The textures and melodic/harmonic interplay create something beyond the music, beyond its context, leading the listener into some shining palace where each moment lingers infinitely as it unfolds its wisdom. The entire point is that it’s not quantifiable. Dolphy seems to say that music should break down limitations. The destination would be unreachable by limited, traditional means (like you can’t get through the gates dragging a set of preconceived notions). All too often there is a disbelief that this album reaches the level it does.

Dolphy’s solos used dramatic intervals and a host of quite unique sounds: honking, buzzing, and anything else that suited the music. A remarkable improviser, Dolphy could give anyone a run for their money (like John Coltrane during their 1961 stand at the Village Vanguard). He was an accomplished multi-instrumentalist. ‘Out to Lunch!’ displays his three primary tools: the bass clarinet, alto saxophone, and flute. His style was remarkably vocal. Evocative and intelligent, Dolphy was an immaculate composer, stylist, instrumentalist, and bandleader.

The group is entirely comprised of superstars, though some were just getting started at the time. Bobby Hutcherson on vibes, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Tony Williams on drums, and Richard Davis on bass provide limitless raw talent while still cooperating from beginning to end. They keep pace with the breakneck rhythms (like 5/4 or 9/4 time) and Dolphy’s explosive solos.

Freddie Hubbard employs his flashy style in full contrast to the more subdued performances by Hutcherson, Davis, and Williams. Richard Davis pulls everything into new territory with his subtle explorations and refusal to hand in a standard performance. Tony Williams, just 18 years old, is loose and explorative. Bobby Hutcherson at times shows his lyrical side, but his brightest moments come through improvisational responses — bangs, clangs, and dribbles all land perfectly.

The songs are each remarkable in many ways. “Hat and Beard,” a homage to Thelonious Monk, portrays the man’s genius and his quirks. “Something Sweet, Something Tender” is exciting and difficult to categorize. “Gazzelloni” (a nod to the flautist) stretches stylistically, while “Out to Lunch” wanders innocently. “Straight Up and Down” is the most comical.

Before Blue Note released this album, Eric Dolphy was dead. Not appreciated in America, he moved to Europe after recording ‘Out to Lunch!’. He died from his diabetes, a condition he never knew he had. This wasn’t the only great album he created. Dolphy contributed as a sideman to countless classics and released many amazing recordings during his lifetime. The posthumous Last Date captures some of his ever-expanding visions of his final weeks in Europe a few months after recording this album. ‘Out to Lunch!’ has beautiful compositions and dazzling performances. It is a document of just what people are capable of. There may be records with seemingly less structure (“freer”) but none with more passion. Dolphy’s flair for life suspends time briefly. For a few minutes, everything that could be, everything that should be, is.