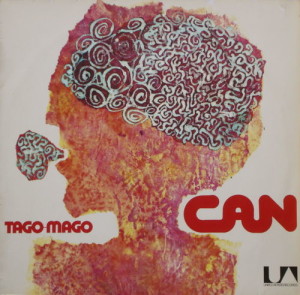

CAN – Tago Mago United Artists UAS 29 211/12 X (1971)

CAN was perhaps the greatest German band ever. Highly influenced by James Brown, The Velvet Underground, and classical, CAN defined electronic rock. Far ahead of their peers, the group never enjoyed much more than a cult following. Kraut rock may now be an obscurity, but the popularity of modern electronic music makes CAN very appealing to virgin ears.

CAN’s musical conception is broad and sweeps out large chunks of space. Most cuts on Tago Mago run from seven to eighteen minutes. Roots in psychedelic rock, R&B/soul, and blues are clear in hindsight. The funky drive from one of rock’s greatest rhythm sections takes over the first half of the double-LP. Jaki Leibezeit on drums and Holger Czukay on bass produced extended comic trances. The rhythms used were unlike anything at the time, but now sound quite akin to sampled loops.

Tago Mago is an enormous work that covers diverse terrain without missing a step. Japanese singer “Damo” Suzuki covers enormous territory. He moves from endless vamps, to impassioned cries, to processed experiments (only Yoko Ono dared as much). “Paperhouse,” driven by the glorious guitar of Michael Karoli and the sublime keyboards of Irmin Schmidt, rocks like a Funkadelic tune. “Oh Yeah” and “Halleluwah” move as if a pack German James Browns are chasing you with a funky stick.

Exciting experimentation is CAN’s greatest asset. “Aumgn” developed by randomly overdubbing the recording tape. This process, as identically done with spoken word years before by William S. Burroughs, and followed Steve Reich‘s iconic “Come Out” by a few years, and predates hip-hop turntable mixing in the South Bronx by a year or two. CAN eases into the closers “Peking O” and “Bring Me Coffee of Tea.” Atmospheric space towards the end of Tago Mago largely dispense with traditional song format. The funky beats of the first few tracks disappear, leaving just sound ebbing and flowing.

This is two albums in one. What begins anchored by identifiable roots closes on the level of an avant-garde Stockhausen composition. The album expands your horizons; yet, CAN is always present to guide through this free trip to paradise.

The wide path cut by Tago Mago is consistently articulate. CAN expertly maintains an immediacy while slowly unveiling their abstract themes. Brilliant experiments are still danceable (“Halleluwah”). Afrika Bambaataa described Kraftwerk as “some funky white boys.” CAN were the godfathers of funky white boys. This work makes a clear connection between avant-garde rock and electronic music.

Mainstream music has accepted CAN’s music, though credit is still lacking. Influence may have been indirect, but CAN proved to be decades ahead of just about everyone else.