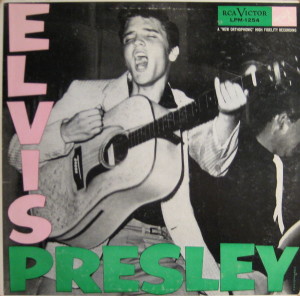

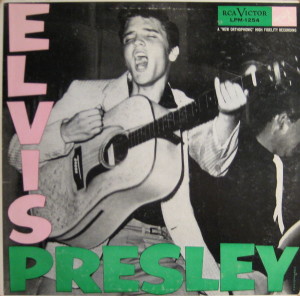

Elvis Presley – Elvis Presley RCA Victor LPM-1254 (1956)

It is impossible to consider the state of American social fabric in the mid Twentieth Century without factoring in Elvis. The magic of Elvis’ early career was that he was this “other” when it came to the characteristically straight-laced 1950s mainstream culture. He took just about every element of unacceptable subculture and threw it together in a seamless, integrated package. C.A. Swanson & Sons introduced the “TV Brand Frozen Dinner” in the 1950s, and it featured a complete meal separated into divided compartments. Take that as a metaphor for the era. Elvis represented all the food commingling, a stew that crossed all the boundaries and dividing walls. There were poor, rural, hillbilly country elements, there were bits of raucous blues and r&b, and more, and it all came together as this new thing people called rock ‘n roll. The music drew from black and white culture at a time when ugly Jim Crow segregation still ruled. But this music was a powerful shot across the bow of the status quo, a warning sign that segregation and the thinking behind it didn’t work. Some truck driver kid from Memphis crossed over. And his undeniable charisma and energy just didn’t leave room for doubt that the most compelling argument was on the side of a new (younger) generation and their new way of thinking. When Elvis famously went on the Ed Sullivan TV show and his gyrating hips couldn’t be shown on camera while he danced and performed because of what they suggested, it is telling that Sullivan still had Presley on, because there was simply no denying that he had something compelling to offer that people identified with. Sullivan had no choice but to accept it. Elvis wasn’t trying to wage a cultural war. But the size of his talent, like that of Louis Armstrong a generation earlier, transformed the cultural fabric. He represented the most successful kind of revolutionary: one that almost naively didn’t recognize or seek change but instead suddenly and completely offered a viable alternative that left the old ways obsolete. They call those paradigm shifts.

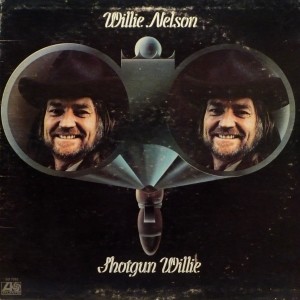

Elvis had begun his career with the tiny but now legendary Sun Records in Memphis, Tennessee. But as Presley started to gain some attention, label owner Sam Phillips sold his contract to RCA Victor in late November 1955 for $40,000 (Phillips made a fortune by investing that money in the new Holiday Inn hotel chain). RCA producer Steve Sholes took Presley to Nashville and began recording songs. “Heartbreak Hotel” was released as a single, and after Elvis made a series of appearances on television for The Dorsey Brothers’ “Stage Show” the single became a smash hit. A few weeks later, Presley’s debut long-player Elvis Presley was released. The rest, as they say, was history.

This album was remarkable in that the LP format was still a new prospect. There were no accepted formulas for how it might work for rock and roll music, if at all. Singles were still the dominant medium. It featured a few leftover recordings from Sun Records (“I Love You Because,” “Just Because,” “Trying to Get to You,” “Blue Moon”), plus new material recorded with Sholes. Elvis tackles covers of some of early rock and R&B’s biggest talents, Carl Perkins‘ “Blue Suede Shoes,” Little Richard‘s “Tutti Frutti,” Ray Charles‘ “I Got a Woman,” The Drifters‘ “Money Honey.” But he also ventured into the territory of Hollywood show tune balladry with Rodgers/Hart’s “Blue Moon.”

Although Elvis was a hot commodity and starting to receive more and more attention, he was still unproven and not yet a big star when he recorded Elvis Presley. As reviewer timregler writes, “so what we get is Elvis on his own terms . . . .” There is something still raw, uncertain and dangerous about this music. The Sun recordings feature Presley with mostly just an electric guitar and acoustic bass (plus drums on one track), while the RCA recordings add piano and drums for a fuller, more elaborate sound. The Sun tracks have the label’s characteristic reverb, leaving a faint feeling of spooky, otherworldly distance. That atmosphere is felt most strongly on “Blue Moon.” The punchy numbers “Blue Suede Shoes,” “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Cry (Over You)” and “One-Sided Love Affair” benefit from the drive they provide that frees Elvis’ vocal acrobatics to develop more nuance. If Presley’s earliest Sun recordings didn’t make explicitly clear the man’s range, it was undeniably apparent when the later RCA recordings sat next to them. The earliest attempts at pop balladry are here. Although in some respects this remained Elvis’ weakest skill at this moment in time, he demonstrates a lot of potential, if nothing else, in songs like “I’m Counting on You.” Elvis’ surprising growth as a singer, together with more elaborate production in the coming years, would improve his prospects. Yet the multifaceted approach of mixing up-tempo rockers with slow ballads would make this LP a defining statement and standard against which rock and roll albums (and pop music albums in general) would be judged for decades to come. The songs may not all be great, but there was practically no filler here. This was put together as a full album of material rather than a few preexisting singles cobbled together for re-release or a few singles padded with many inferior outtakes.

The vocabulary of this album is romance, tempered with some self-assured posturing. This made perfect sense in an era of claustrophobic conformity. It represented a more unbridled form of individual expression. But the predominant language of romance made it accessible yet also less directly objectionable than, say, the more intellectual jazz and beatnik music of counter-cultural circles. Elvis had stumbled through the unlocked back door of America’s entrenched cultural conservatism. And it seemed like everyone else followed — though picking up on one line of critique this use of romance may have contributed to the hypersexualization of women in coming decades. While certainly Elvis was not the only musical innovator of his day, the magnitude of his rather sudden and surprising fame made him an easy reference point as a kind of dividing line between different eras of popular culture.

Elvis became the fist popular music superstar of his kind in large part due to the timing of his arrival. In the 1950s, the United States was the biggest economic superpower in the world (parts of Europe still being in ruins). The combined legacies of the so-called Progressive and New Deal eras, together with the economic opportunities created by massive World War II industrialization, created a unique environment in which the powerful (willingly or unwillingly) gave working people the greatest share of wealth and power that they had ever experienced in the history of the nation. Those gains would be attacked relentlessly, and would begin to steeply erode in less than two decades, but they still presented themselves as new and seemingly permanent changes as Elvis came to the fore. This was the double whammy of Elvis’ stardom. He was the choice of both the young and of the working class. And he was their ally in the sense that he was a cultural commodity, an emblem of uncontrollable cool and swagger, the sorts of characteristics that entrenched interests can never convincingly deliver. But while cultural mavericks exist all the time, Elvis’ records sold millions of copies, proving not only in cultural terms but also in terms of cold hard dollars (the language of entrenched interests) that he had tapped into something that was tangible from any angle.