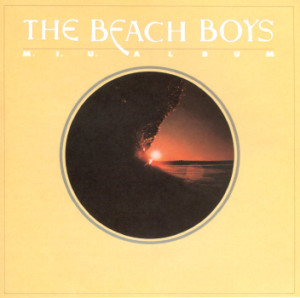

Alex Chilton – Like Flies on Sherbert Peabody PS-104 / Aura AUL 710 (1979)

In 1983, Neil Young had a dust-up with his record label Geffen. Upset that his krautrock-inspired album Trans (1982) sold poorly, they rejected his country album Old Ways (later released in 1985) and an executive insisted he record a “real” rock ‘n roll record. Angered, Young went out and decided to make his next album Everybody’s Rockin’ (1983) by taking the executive’s statement quite literally. So he made a collection of old rockabilly covers and soundalikes — the kind of “real” rock ‘n roll that reached its peak nearly three decades earlier. It was this kind of nobly bratty behavior that made fans love Young. But the resultant Everybody’s Rockin’ album was merely a competent genre exercise without any character of its own — though, in Young’s defense, the label did cut off the recording sessions before the last two songs were complete, leaving it short of his full vision. So the album is frequently viewed as a lark, either (sympathetically) fun and forgettable or (unsympathetically) simply boring and anachronistic. All this is relevant because in many ways it is the complete opposite approach to a very similarly bratty premise adopted by Alex Chilton on his solo debut album Like Flies on Sherbert (working title: Like Flies on Shit).

AllMusic Guide reviewer David Cleary had this to say about the album:

“Production values are among the worst this reviewer has ever heard: sound quality is terrible, instrumental balances are careless and haphazard, and some selections even begin with recording start-up sound. *** Many of the songs here stop dead or fall apart rather than ending properly. Instrumental playing is universally slipshod and boorish, and vocals are sloppy and lackluster.”

All of these comments raise the question, “by whose standards?” Alex Chilton willfully disregards convention, employing improper, careless and sloppy techniques as a deliberate choice. Don’t like it? Fuck you. Alex Chilton didn’t care. He was going to either revolutionize music or be derided. Right after Chilton’s death in 2010, former associate Chris Stamey recounted a story from the early 1980s when Chilton was working as a dishwasher in New Orleans, when a co-worker said, “Yeah, Alex, you’re right, and the rest of the world is wrong.” Chilton reflected to Stamey, “You know, I think he was really on to something.” What happened with Like Flies on Sherbert was very much to Chilton’s liking. He once recalled to journalist Robert Gordon, “My life was on the skids, and ‘Like Flies on Sherbert’ was a summation of that period. I like that record a lot. It’s crazy but it’s a positive statement about a period in my life that wasn’t positive.” It Came from Memphis (1994). So, the conservative view is that Like Flies on Sherbert is a poorly recorded roots rock album like an album by The Band (Stage Fright, etc.). But to be fair to this album’s premise it must be admitted that it embraces a rough, do-it-yourself aesthetic that is less overtly entertaining and more of a shared communion in outsider status.

Chilton had been living in New York city before recording the album, hanging around CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City. He took to the punk ethos. He didn’t play straight punk rock. Rather, he obliquely incorporated the punk attitude into unraveled rock and roll, country and disco songs. The approach is often cited as a precursor to a lot of 1990s rock like Pavement, and even some 80s rock from bands like Flipper. That was the thing with Alex, who always seemed to be working about 5-10 years in front of trends, creating and inspiring them without every really benefiting — ahem, capitalizing — from them. The man’s career was a cautionary tale of the perils of success and the way that no amount of artistic brilliance can make up for lack of distribution and label support when it comes to making a living through music.

The album was released first on Peabody in the US, then shortly thereafter on Aura in the UK. The UK version dropped “Baron of Love, Part II” and “No More the Moon Shines on Lorena” but added “Boogie Shoes.” It is probably appropriate that not even the track listing is deemed sacred here! The wrecked KC & The Sunshine Band cover “Boogie Shoes” is a stronger opener than the talking blues “Baron of Love, Part II” but the rave-up of the 1931 Carter Family song “No More the Moon Shines on Lorena” is worth having in the mix. Various reissues have appended some or all of the variant songs as bonus tracks.

With all the interest in dilapidated, lo-fi pop decades later, it seems that Like Flies on Sherbert deserves its due as pointing toward that same aesthetic of downward social mobility, and the ragged glory of penniless cultural sophistication. In Holly George-Warren‘s biography A Man Called Destruction (2014) Alex is revealed as a Trotskyist who grew up in a bohemian household in Memphis, part of a burgeoning and uniquely Southern kind of leftist counterculture. From such roots Chilton builds up a musical worldview that defends the dignity of every failure. His music, perhaps like his politics, abhors competition, and finds a place for those who would otherwise be the losers right along those who would be kings and queens. Taking such a stand is not the sort of thing that slides by in a society ruled by competition.

There is something of a choice given to people living under capitalism, though: become part of the system, or be crushed by it. The system admits no one on terms other than its own. But there is a third option, the one that Alex Chilton took. He nominally goes along with the system. On occasion, he’ll even smile as he does. But then, he goes and defiles everything that the system values. This is not a frontal attack. It is something entirely different. It is more of a decay from the inside. The idea is to introduce an irritant or pathogen, like a virus, that the system can’t fight and instead must eject to save itself. Think about this for a moment. The idea is to be insufferable! On Like Flies on Sherbert that is accomplished through a kind of sonic tantrum. And what a tantrum! Chilton had an interest in psychoanalysis (and horoscopes). During the May 1968 uprisings, students graffitied walls with psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich‘s name (Chilton was an admirer too) and threw copies of his The Mass Psychology of Fascism at police. Alex’s music was not far off, though it was like a rebellion standing in one place. It simply transforms its own self-identity to be something that passively irritates the system. From a place of disappointment and hopelessness, it forges something that breaks with those conditions. They key is that like an irritant or pathogen that the body tries to reject, or a puzzle piece that simply is the wrong shape and must be set aside, the “system” that is the music industry casts off music like this. Once outside the system itself, a space is created that the system doesn’t try to crush (perhaps for fear of contamination). This is the genius of people like Alex Chilton.

Music like this does something akin to what Jean Genet‘s writing did: it takes the standards of a society that rejected the author/performer and willingly pursued what it deemed vices (Genet wrote in Journal du voleur [The Thief’s Journal]: “Repudiating the virtues of your world, criminals hopelessly agree to organize a forbidden universe. They agree to live in it. The air there is nauseating: they can breathe it.”) Its methods also recall the way filmmaker John Cassavetes worked: recording uninterrupted, fleeting performances that would never occur if the relentless, self-conscious drive for unblemished takes took precedence over spark and spontaneity. It may not quite be détournement, because it doesn’t claim to be a complete reversal of the prevailing order and accepts participation in it, but it is still close. This is worlds away from what Chilton did with The Box Tops and Big Star.

It makes sense that this album arrived in its own time. Chilton was a product of the 1960s counterculture, not as a leading advocate but as someone carried along with it. He suffered as the counterculture and the New Left incurred political losses. As in the 1970s, he found that opportunities dried up and that years of partying and hedonism didn’t add up to much. The punk attempt to break off from corporate commercial imperatives appealed to his sensibility. But as a southerner he was kept somewhat at arm’s length by many of the punks (and their record labels and venues). So he did his own thing, which at arm’s length didn’t have to adopt all the same feedback and power chords of typical punk rock, but instead looked back to vintage rock ‘n’ roll, blues and country/folk.

A song like “I’ve Had It” recalls “Blank Frank” from Eno‘s Here come the Warm Jets (a Chilton favorite). Only about half of the songs are Chilton originals. And those mostly chug along with a hook that comes across only crudely. The swampy blues cover “Alligator Man” is a freewheeling success, with Chilton caterwauling in his upper register. Co-producer Jim Dickinson plays guitar (ineptly) on some of the songs, to underscore the anti-perfectionist tendencies of the album.

Like Flies on Sherbert has maintained a cult following. It documents a kind of cathartic approach to music — going back to a Neil Young comparison, like Tonight’s the Night (1975). While not exactly a “great” album, it has earned admiration. This is easily the most essential of Chilton’s solo output, even if he has plenty of other worthy solo recordings.