Link to a film review:

Category: Film

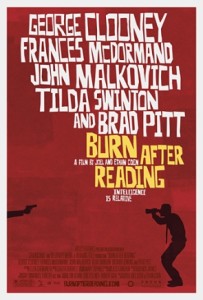

Burn After Reading

Burn After Reading (2008)

Focus Features

Directors: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

Main Cast: Frances McDormand, John Malkovich, George Clooney, Tilda Swinton, Brad Pitt

Admittedly, the only Cohen Brothers movie that I’ve ever liked is The Hudsucker Proxy (1994). But I came to Burn After Reading not realizing it was a Cohen Brothers movie. Anyway, the plot here is one part expanded love triangle (akin to Sartre’s No Exit) and the other part zany spy comedy. Unsurprisingly, the characters are caricatures, and the audience is supposed to smugly view themselves above them. Each runs about chasing after an image of themselves they want others to adopt, be it Makovich’s uncompromising intellectual, Clooney’s athletic lothario, or McDormand’s youthful striver, yet they all find no one really interested (much like Jason Alexander‘s character George Costanza can’t find anyone to adopt his desired nickname “T-Bone” in an episode of TV’s Seinfeld). The film wants to be kind of like a Kafka novel, probing the emptiness of formal law and order, but it stumbles as it mocks pretty much all of the central characters. Nobody in the film ever sublimates their venal greed and desires. Brad Pitt’s character is about the only one the filmmakers can’t mock effectively, because they never really present him as having any ambitions beyond exercising and being a dope. Put this next to Orson Welles‘ Kafka adaptation of The Trial (1962) and it seems a bit weak. Sure, there is some good acting and a few funny gags. But the film sort of preys upon “simple” folks as targets for ridicule. It would be a far more subversive film if it included some of the CIA bigwigs or other peripheral yet powerful characters in the film and also held up their stupid desires and dreams for ridicule (perhaps like early Miloš Forman films). As it stands, Burn After Reading is about halfway to a good film. But only halfway.

Minnie and Moskowitz

Minnie and Moskowitz (1971)

Universal Pictures

Director: John Cassavetes

Main Cast: Seymour Cassel, Gena Rowlands

Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz is the story of a couple’s oddball romance. The basic plot is adapted from that of Marty (1955). But Cassavetes puts a wider social chasm between the two main characters. Seymour Moskowitz (Seymour Cassel) is a sub-proletariat hippie who works as a car park attendant, whose mother sees him as a hopeless case with a downward trajectory in life. Minnie Moore (Gena Rowlands) is a museum curator who rubs shoulders with wealthy art aficionados, though she comes from a middle class background. Despite characteristically uncomfortable scenes and intensely raw acting, this is Cassavetes at his most conventional and accessible. Yet this film succeeds on multiple levels, not just as a light comedy/drama. The main characters have a tumultuous relationship. There is nothing easy about them coming together. They have plenty of inhibitions, brought on by the stress and fears and discrimination and loneliness and limitations of their individual lives. It is hard for them to let go of those things, however much misery those things bring them. And the people around them are mostly selfish and rude, or just unable or willing to open up to others. Minnie, in particular, has a hard time accepting Seymour, because she is part of a much higher social strata that tends to sneer at the likes of him. Her real-life husband Cassavetes plays her (ex) boyfriend Jim, a married man who won’t leave his wife. She is surrounded by people who seem only interested in how she fits into plays for status — Jim with his stable of women or a blind date (Val Avery) trying to be less of a sad sack without a wife like a successful guy like him “should” have.

But the real heart of the film is that the tumult and conflict all serves to bring two people together. Their relationship is a choice, and they choose to transcend the many, many obstacles put in its way. The sweetness of Minnie and Moskowitz is that it is a romance tale that suggests social inequities can be overcome, and that relationships can play a part in making the world a more accepting place. This is what distinguishes it from Marty, which is a wonderful movie with superb acting but one that relies upon the (essentialist) idea of characters settling for something and discovering what they “really” are and “really” want. Cassavetes’ film is about the characters becoming something more than what they were at the start. That is especially true for Moskowitz, who goes from being someone drifting along on nothing more than simple pleasures to having a larger purpose. This may not be Cassavetes’ best or most ambitious work, but it is one of his most likable films.

FBI Informant Exposes Sting Operation Targeting Innocent Americans

Link to a news segment entitled:

“FBI Informant Exposes Sting Operation Targeting Innocent Americans in New ‘(T)ERROR’ Documentary”

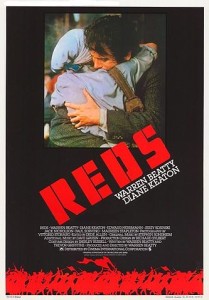

Reds

Reds (1981)

Paramount Pictures

Director: Warren Beatty

Main Cast: Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrmann

Although there is frequently an accusation of “Hollywood Liberalism,” after the McCarthy witch hunts of the 1950s, the political left had a fairly low profile in Hollywood post-WWII. During the “New Hollywood” movement, beginning in the late 1960s, that changed, somewhat. In the early 1980s, at the tail end of that movement, there were at least a couple of politically leftist epics — no less — that represented some of the last and best examples of what was possible for the political left working in conjunction with big business movie making (the other being Heaven’s Gate (1980)).

Reds is the biographical story of John “Jack” Reed (Warren Beatty), the journalist and author of Ten Days That Shook the World (1919), an account of the October (Bolshevik) Revolution in Russia, and his companion Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton). Reed is the only American buried in Red Square in Moscow. The film opens at the beginning of WWI. One of the finest moments in the entire film comes in the first few scenes when Reed, a journalist just returned from the front in Europe, is asked to speak at a high society gathering about the real cause of the war. He stands up and says, “Profit.” He then immediately sits back down. Could there be a clearer explanation in any number of words? Interspersed with the historical dramatizations are documentary interviews with “witnesses,” people who knew Reed and Bryant long ago retelling anecdotes for Reds. Some were friends, while others don’t have anything particularly kind to say. Jack Nicholson portrays playwright Eugene O’Neill. His misanthropic character has clearly been a model for plenty of other Hollywood actors in later films.

Many leftists despise Reds, often because it subordinates the October Revolution to a romantic melodrama. This seems unfair. If the romantic drama were not in the forefront, this would not be a Hollywood movie. As it is, there are hardly any Hollywood films that paint authentic leftist revolutionary activity in such a positive light. Of course, Michael Cimino‘s Heaven’s Gate overcomes all the difficulties with Reds‘ treatment of romantic melodrama (Kris Kristofferson ends the movie married and bored on a yacht) — though at the same time Cimino’s film was butchered to a condensed version that bombed, only to be resurrected with a director’s cut later on.

It is difficult to maintain a suitable pacing throughout an epic. Reds does well in that regard, even if things slow a bit toward the end when during the midst of the post-revolution civil war the film, paradoxically, focuses on the powerlessness of the characters. There are bits of Ten Days That Shook the World that might have added some levity, like when the only restaurant open after Reed investigates the storming of the Winter Palace is a vegetarian restaurant called “I Eat No One” with a picture of Leo Tolstoy in the front window. But, such changes would, again, make this something other than a Hollywood romance film.

As it stands, Reds is one of Hollywood’s finest dramas of the early 1980s. Beatty and Keaton are fantastic, Keaton as someone from a privileged background desperately striving to cultivate cultural capital in the artistic/journalistic world and Beatty as the slightly vain and adventurous but nonetheless immensely talented figure who made important contributions to the historical documentation of the October Revolution in the English language.

Matthew Yglesias – I Boldly Went Where Every Star Trek Movie and TV Show Has Gone Before

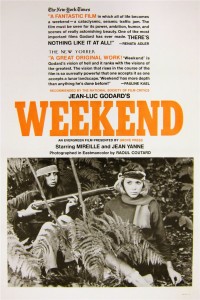

Week-end

Week-end (1967)

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Main Cast: Mireille Darc, Jean Yanne, Jean-Pierre Léaud

…and Godard enters his Maoist phase. You’ve probably heard or read summaries before. This movie is about the collapse of the capitalist system that sustains the Western World, and the idea that more meaning in life will emerge after its collapse. But the best part is that for all the depravity and vice, it’s hard to tell exactly when Godard is joking. Oh, and the visual metaphors are astoundingly unique. This one tends to be a favorite of die-hard Godard fans, and count me among them.

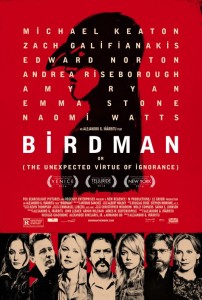

Birdman

Birdman: or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014)

Fox Searchlight

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Main Cast: Michael Keaton, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Zach Galifianakis, Naomi Watts

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Actors Edition.

Birdman is a film that wants to be deep. It concerns an aging actor Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), whose career has become defined by a title role in a superhero movie franchise. But now he is organizing (as writer, director and actor) a stage adaptation of the Raymond Carver short story collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love on Broadway. Unhappy and frazzled, he brings in a well-known stage actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) as a replacement for one of the male stars. His daughter (Emma Stone), back from drug rehab, is “assisting” him as a way to keep her occupied. The film builds on intense scenes with long shots, set in the bowels of the theater, on the stage, and in the dressing rooms. Intermittently through the film, Michael Keaton’s character hears a voice in his head, and he seems to possess the ability to fly, move objects with his mind, and otherwise really be a superhero — or is this just a psychotic break brought on by the stress of the theater production?

The early part of the film sets up the conflicts, between the actors in the Carver adaptation and between Riggan Thomson and his legacy. Mike Shiner is a talented actor who we are to believe exists in two diametrically opposed realms: that of the “real world” where he is despised, impotent and rejected, and that of the stage, where he is adept, creative and appreciated. To impress the importance of Acting and the Theater, his character, and the others, behave badly and obnoxiously, parading about naked, smashing things in bars, and engaging in public arguments and fights. The main characters storm about the building, often met with bewilderment by the theater’s staff and technicians. Yet the staff and onlookers seem powerless to engage any of this. They are onlookers, not able to play a role in the tribulations of the Great Artists. The last half of the film sets out the resolution of those early conflicts. Michael Keaton gets most of the screen time toward the end. The ending, as we’ll see, feigns ambiguity.

The fatal flaw of this film, except for pretensions to depth that it doesn’t earn, is that it relies on a con. While Riggan Thomson seems to want to make deep art not just commercial movies, the Thomson character is always obsessed with status and power. He has a lot of money (financial capital), which, by personally putting up considerable funding for his play, he attempts to trade for greater recognition as an artist (cultural capital). In this, the theater is somehow seen as loftier in a hierarchy of arts, the audience of Broadway plays deemed more significant than the (presumably) middle-American moviegoers (and Times Square tourists) who liked Thomson’s turn as Birdman in the movie franchise. During a run-in with a theater critic in a bar, who calls out Thomson for his attempt to convert his movie celebrity into a different kind of cultural status on Broadway — and rather implausibly states in direct terms her role as a guardian of middlebrow tastes who must oppose such conversions of social capital — he angrily proclaims what a risk he’s taking. As the audience, we are to forget that this risk is just a gamble, like any other in (casino) capitalism, from a player who simply started the game with more chips than the others. The critic says her complaint is that Thomson is taking up theater space that could be put to better use (we are to infer she means someone with pre-existing cultural capital in the New York City theater scene), and promises to destroy the play with a scathing review, confident that she alone holds the power to do this (something the film undercuts, given the insatiable craving that fans seem to have to see Thomson in, well, anything).

There is another, earlier scene in which the daughter excoriates Thomson for failing to understand his insignificance — apparently unaware that this is the set-up for an old joke. That scene sits almost in isolation for a time, until the final scenes of the film provide a rebuttal. By the end, we hear that the voice in Thomson’s head (it is the Birdman character) explains the truth to him, and on the question of whether he is a superhero or a psychotic, his daughter in the final scene appears pleasantly surprised that rather than committing suicide by jumping out a window, he might really be flying. Rather than convince her father of his insignificance, instead it is her who ends up convinced of his exceptionalism. She also instructs him about online social media — making a fool of oneself publicly is the new way to wield power over a fan base. He just needed to understand contemporary marketing tactics a little better, see? Other scenes in which tense family relations come up, seem to be resolved through professional prestige: if Thomson’s play succeeds commercially or critically (does this film see any distinction between the two, really?), then all his other problems are solved.

The film ends on a note seemingly lifted from the iconic Jimmy Stewart family film Harvey (1950), about an alcoholic man whose best friend is a giant rabbit who may or may not be a figment of his imagination. Yet there is none of the heart or sweetness of the Stewart film here. Yes, there is good acting, but the scenes in which the acting is prominently on display are constructed for maximum intensity — with long shot after long shot, many close ups and hand-held camerawork — all meant to focus attention on isolated emotional outbursts strung together in series. While Harvey might be dismissed as a naïve children’s film, it opens the possibility for different ways of looking at the world, in a way in which, from the standpoint of social status, Stewart’s character stands to gain nothing at all from his friendship with a giant (imaginary?) rabbit. In Birdman, Michal Keaton’s character simply looks for the most effective path toward the fame and fortune he desires. There is no question about the path he’s following. He just needs to out-compete the other actors out there in the mean world of professional theater. How?

Birdman suggests that there is Truth. It is masked. But the voice in Riggan Thomson’s head still tells him the something that guarantees his happiness. This is the religious/theocratic core of the script. Thomson succeeds or fails based on whether he recognizes this Truth sufficiently. What we are left with is an apology for fame and status seeking, justified by reference to some higher power that only the exceptional few can access. Left somewhat unspoken in Birdman is how Riggan Thomson came to be a major Hollywood actor. There is a trite story of Raymond Carver congratulating him as a child, convincing him to pursue acting as a career. But it takes much more than talent and desire to succeed in the world. Only people with certain social capital can pursue careers in the arts, often having family legacies in that industry, having wealth that allows for unproductive time spent on artistic interests. So, there is also a hidden fatalism in this film. Thomson is destined to a path, he only needs to believe in it enough. So, to paraphrase Bertolt Brecht from Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner, Riggan Thomson wonders maybe if there is a god, but in his wondering he already decided, and it seems he needs a god, because he would not act in such a way to achieve fame and riches if he could grasp any other way than what those fame and riches seem to guarantee for him in the world. So no existential angst for him. He is absolved of creating meaning for himself. He just listens to the voice in his head. This, supposedly, is the “unexpected virtue of ignorance.” Strangely, it seems lacking in virtue. Greed is good?

Douglas Valentine – Citizen Four: The Making of an American Myth

Link to an article by Douglas Valentine:

“Citizen Four: The Making of an American Myth”

Bonus link: “The Intercept, Mass Surveillance and the State”

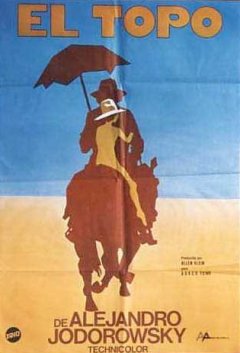

El Topo

El Topo (1970)

Producciones Panic

Director: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Main Cast: Alejandro Jodorowsky, Brontis Jodorowsky, José Legarreta

For most viewers, El Topo (English translation: The Mole) will be the most bizarre western they have ever seen, and maybe even the most unusual movie of any genre they have ever seen. It has developed a cult following, and promoters claim it initiated the tradition of “midnight movies”, though a long dispute between the writer/director/star Alejandro Jodorowsky and the eventual distributor Allen Klein kept the movie largely unseen for decades. Although there are plenty of interpretations floating around, some sympathetic and some not, it is a movie that actually makes perfect sense from the standpoint of psychoanalysis (Jodorowsky studied psychology for a time).

Many interpretations see the movie as being about spiritual enlightenment. Maybe it is. But it is worth taking an entirely unsentimental look at it so see what other interpretations are possible.

The film opens with the black-clad gunfighter El Topo (Jodorowsky) riding into a small village on his horse with his naked son. The village has been ransacked, and there is blood and death everywhere. Jodorowsky locates the criminals responsible — they are led by a military officer. El Topo renders frontier justice and frees the surviving monks from the village and a woman. He leaves his son with the monks, and rides off with the woman. She convinces him to seek out and defeat four master gunfighters in the desert. He does so, and, finding them superior in skill, defeats them through trickery or luck. There is symbolism all over the movie. It is exaggerated symbolism, often religious. The master gunfighters each resemble a different religion. Along the way a black-clad woman whose voice is overdubbed with that of a man joins the pair. The last master that El Topo “defeats” actually kills himself, to prove to that his life means nothing. The woman in black then shoots El Topo, and his body is taken away by a band of physically handicapped or deformed people.

In the second half of the film, El Topo, now with a long beard and resembling some kind of spiritual guru, awakens from a long coma in a cave. He is living among the oddball people, who have been sealed in the cave by the residents of a nearby town. He is able to free the people from the cave eventually, after working as a street performer to beg for money to support them (Jodorowsky had studied as a mime). He is something of a Gandhian, of sorts. But upon releasing the prisoners of the cave, the townspeople murder them. This is a brutal representation of what social elites always do — segregate other classes, and when any possibility of upclassing and escape from ghettoization seems possible they take away that possibility through any means necessary.

Film scholars debate whether Jodorowsky is faithful to his overtly acknowledged influence from Antonin Artaud‘s “theater of cruelty”. He might be, or might not. The surrealist use of symbolism, in a way that both crystalizes and degenerates the meaning of those symbols, presents interesting fodder for that debate at the least. So many of the characters seem almost like Jungian archetypical images, essential representations of elements of a collective unconscious. Yet they live and die before us in the film. They are given gaudy, dramatic representation. But their deaths and flippant usage in the film suggests they are not eternal archetypes.

Jodorowsky is routinely dismissed by certain film critics as a charlatan. This is a rather common occurrence for an artist with anarchist tendencies. Such a position is (rightly) perceived as a threat to the status of critics, etc. who attempt to distinguish themselves on the basis of their position within an established social hierarchy. Jodorowsky is overtly attacking religions, of all kinds, and with it the very concept of a path pre-defined by a social hierarchy. But more than that, he also seems insistent that something else must be put in the vacant space, without demanding or asserting what that something else should be, precisely. The only demand, as such, is for the audience to work at the question.

It may be worth contrasting El Topo with Hermann Hesse‘s novel Siddartha (1922). Hesse’s protagonist leads a spiritual journey through asceticism, then hedonism, then to a middle way that finds him working as a ferryman at a river crossing. This end is a negation of self. The protagonist finds enlightenment. The book adopts aspects of hinduism, but is primarily buddhist. El Topo, in contrast, does not end with the protagonist finding enlightenment. He fails, if that is seen as his goal. But, he also goes from a gunfighter who really exists only to kill, to someone who takes a non-violent, self-sacrificing approach to helping others, falling back to killing (killing the wicked) before he then turns to kill himself, the killer. What is so different from Hesse is that Jodorowosky does not endorse a particular religion. He stages the “deaths” of the major religions, through the symbolic confrontations with the master gunfighters. The second half of his film takes place in the main character’s post-religious existence. He is burdened with the task of finding meaning that is not provided for him. Rather than simply regulating his empathy — not too much or too little, which is really what the “middle way” of buddhism is about — he tries to care for others and materially change their circumstances for the better.

But what El Topo does is to illustrate a very post-modern idea that through failure success eventually emerges. El Topo may die failing to save the people from the cave, but when he dies, a beehive appears, just as upon the death of each of the master gunfighters in the desert. He does not find any final answer or enlightenment, but just as the movie goes on after all of the first four master gunfighters die, there is the implication that there is more beyond the death of El Topo. His children survive to go on into the world further. His ultimate act is to destroy himself. His life, at the close of the film, is a negation.

The sort of definite resolution of a novel like Siddartha was rejected by many filmmakers in the 1970s. El Topo is one such example. Others are Federico Fellini’s Fellini Satyricon (1969), a Jungian interpretation of Petronius‘ fragmentary ancient Roman “novel” Satyricon that is one of the very few cinematic precedents for El Topo, Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s unmade screenplay St Paul, about the founder of the christian church, and Nicolas Roeg‘s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), based on the book by Walter Tevis, about an alien who comes to Earth to save his home planet only to get lost in wealth, celebrity and hedonism. Paul seeks to promote a revolutionary emancipation of christian believers, but ends up losing what he tries to advance under the weight of the contradictory pressures of the church as an institution. The alien in Roeg’s film (played by David Bowie) amasses wealth to build a spaceship to go back to his home planet, but his amassed wealth brings about his downfall as it calls attention to his plans and he is stopped by the vested interests of the establishment. Fellini said of Satyricon that his intent was “to eliminate the borderline between dream and imagination: to invent everything and then to objectify the fantasy; to get some distance from it in order to explore it as something all of a piece and unknowable.” There is much dreamlike symbolism of that sort in El Topo as well. Pasolini’s screenplay is the closest reference point to El Topo’s actions. The collective unity through christian ideals of “holy spirit” are ultimately incompatible with the institution of the church, yet are still noble efforts worthy of revisiting — Pasolini’s script transposed Paul’s life into the WWII era, with Nazis in place of Romans. El Topo tries to change the circumstances of the cave people, but he ultimately can’t change the bigoted townspeople who first trapped the others in the cave. The desire to free the cave people was still a good and worthy goal, but El Topo failed to achieve it. Just as in the first part of the film, he kills the bad guys. In this way, the failure is his own. He fails to move beyond such actions. Yet the entire thrust of the film is to suggest that one must try to fail, fail again, and fail better (to paraphrase Samuel Beckett).