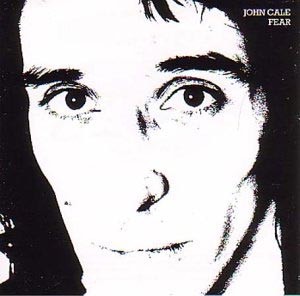

John Cale – Fear Island ILPS 9301 (1974)

John Cale’s music, like most great art, is defined by subtlety. Unfortunately, subtlety is lost on most listeners and many critics. His classical background introduced fresh ideas to rock and roll. So much is made of his association with the origins of punk and with the avant-garde that his range is often overlooked, due to his disregard for divisions between highbrow and lowbrow forms. His music is unique in its own way and difficult to precisely classify.

The guitar plays a central role on Fear. With the combined efforts of Brian Eno and Phil Manzarena, Fear has frequent bouts of guitar fireworks (Eno would electronically process Manzarena’s guitar solos). Simultaneously accentuating the internal textures of the guitar (like John Cage could do for the “prepared” piano) he blends the guitar into the overall collection of sounds. Manipulation of guitar tunings and chord structures make this unique. While first listening to the album, it’s not easy to say “that guitar is tuned differently!” But it becomes obvious that other music doesn’t sound quite the same. Other performers include Andy MacKay, Fred Smith, Judy Nylon, and Richard Thompson. Superb performances by the Cale’s studio band fully realize his visions. Demanding and all-encompassing compositions come to life through the superb musicians that bring just enough life and improvisational character to the recordings.

Fear has some of Cale’s most concise pop songs. “Buffalo Ballet” is a ballad of railroads on the Great Plains. Cale’s lyrics were never that interesting and Fear is hardly an exception (which is what made Lou Reed/John Cale collaborations so powerful). Cale is a more a composer than lyricist. He tells his stories with music, not words. Lyrics are just a minor part of the grand arrangements. All too often lyrics are used as the sole basis for determining the “quality” of an album. John Cale provides a counterargument against such evaluative methods.

Always pushing the limits, Cale’s background covers impressive territory. He performed with John Cage as a pre-teen. Then Aaron Copeland arranged for a scholarship for the Welsh-born Cale to study in the states. Cale moved into the avant-garde cadre stateside, including a much-heralded stint with The Theater of Eternal Music (a/k/a La Monte Young’s Dream Syndicate). His move to rock and roll began when he and fellow Dream Syndicate member Angus MacLise joined Lou Reed to promote the single “(Do the) Ostrich” as the band The Primitives. Out of the Primitives grew The Velvet Underground. When Lou Reed felt threatened by John Cale’s abilities, Cale left the Velvets. Originally unreleased Velvet Underground recordings like “Stephanie Says,” “Ocean,” and “Ride Into the Sun” point to the direction Cale wanted the group heading. Those demos and outtakes issued years later show subtle complexities very similar to the music on Fear.

This music is almost punk, but that’s not quite the best descriptor. John Cale was in many ways the godfather of the punk sound (Lou Reed being the godfather of its ideals). Fear was the factor that urged Patti Smith to use Cale to produce her seminal debut album Horses.

If anything, Cale’s immense talent ruined any chance of popular appeal outside the U.K. He so expertly incorporated his experiments, they often seem like pop songs on the surface. But that is hardly the whole truth. “Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend” uses Cale’s distinctive reverse dynamics. A combination of rhythmic and dynamic shifts is substantively the opposite of the traditional pop format; however, the result fits perfectly with a pop aesthetic. Cale’s piano, with the brilliant use of space in the opening bars, features his characteristic choppy, pounding chords.

The only familiar Cale technique largely absent on Fear is the drone. Such a forceful part of his repertoire (even appearing on producing efforts like The Stooges and his film scores), we get slightly altered versions on “Gun” and “Ship of Fools.” Not quite drones, he employs almost pedal tones (a technique J.S. Bach used by repeating a tone while chords change around it) with static chords or straight pedal tones.

“The Man Who Couldn’t Afford to Orgy” reveals Cale’s infatuation with The Beach Boys and Brian Wilson’s heavenly California harmonies. You still get an insider’s views on Warholian episodes with “Ship of Fools.” Always though, the melodies are sweet.

John Cale didn’t have a particularly memorable singing voice, but he had more technical vocal ability than usually credited. He said that one basic motivation of rock & roll is to scream and get paid for it. On many levels, that is a remarkable truthful statement. Cale does move from sweet vibrato to unbridled screams — always executed with precision.

Where Paris 1919 was a mellow portrait of home, Fear collects John Cale’s great rock and roll experiments. Personal revelations, anecdotes, and biographical portraits give Fear a well-rounded scope. Cale’s experience as a producer made this album possible. Like a grand opera, Cale finds the perfect use for each element. While his uniqueness may have hindered his popular appeal, it certainly made for great music. In my mind, John Cale is a tremendously influential musician. Always in his own way. Like Eric Dolphy (the jazz musician), the right people knew he was great, but most people miss his greatest innovations.

On a personal level, I find John Cale remarkable. He devoted time to the high & “proper” classical arena, and to “dirtyass rock and roll” (to reference the song from Slow Dazzle). In a sense, he was never fully accepted by either camp. Some rockers considered him too elitist coming from a classical background, while the classical people though he wasted time making stupid pop music. But there are many examples that show how both sides are wrong. John Cale made great music. The discussion should really end there. He was never properly accepted as a genius. Musical Renaissance men like Cale face a bias, but only from the ignorant. I respect a man who can continue to create his own art despite little public acceptance. He was right and the world wasn’t. Unlike Thelonious Monk (who chose to play different than everybody else in public, but privately played conventional stride styles), John Cale was different. He just went with his instincts.

![Your Past Comes Back to Haunt You: The Fonotone Years [1958-1965]](http://rocksalted.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/yourpastcomesbacktohauntyou-300x300.jpg)