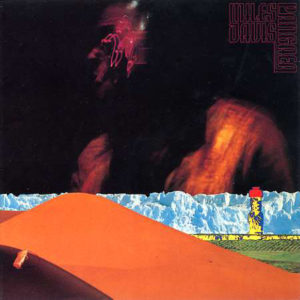

Miles Davis – Pangaea CBS/Sony SOPZ 96~97 (1976)

Yet another great album from Miles’ fusion period. Recorded on February 1, 1975 at Festival Hall in Osaka, Japan, this was the evening concert that followed the afternoon concert released as Agharta. Both albums were originally released only in Japan. Agharta was then released in the U.S. in 1976, but Pangea did not see a U.S. reissue until 1991. Another Japanese-only concert recording, Dark Magus, from a 1974 show, was released in 1977 and only reissued in the U.S. in 1997. None of these albums was particularly commercially successful.

“Zimbabwe” takes up the entire first LP. Early on the band plays with a quick, anxious tempo. Miles uses a slow kind of phrasing, in complete contrast to the rest of the band, like they are rushing to get the music across but somehow he has all the time in the world. Gary Bartz was probably the best and most effective saxophonist to play with Miles in his fusion years, but Sonny Fortune (featured here) might come second. This songs has a sleek feel. “Zimbabwe” is actually a suite or medley of shorter songs played together without interruption.

“Godwana” on the second LP starts with a kind of semi-ambient, long and slow approach with Fortune on flute and Miles playing atonal blocks of notes on a keyboard. Most of the band later drops out and Pete Cosey plays an African thumb piano. He almost certainly got the idea from having played with Phil Cohran and the Artistic Heritage Ensemble. Cohran had an amplified thumb piano he called a “Frankiphone”. The problem here (at least on the 1991 CD reissue) is that Cosey’s thumb piano is so far down in the mix it is barely audible, reduced to sounding like faint clicks in near silence. After bringing the entire concert practically to a standstill, the band builds back up gradually. Cosey rips into a psychedelic guitar solo, and Miles jumps over to keyboard. Al Foster keeps the brutally hard rhythms going. Foster was an under-appreciated force in the band. The song slows again when Miles plays almost solo — again this might be merely a mixing issue with the CD reissue. Towards the end there is a lot of electronic noodling, something that probably seemed odd back then but which simply seems ahead of its time now given the forms of electronic music that came later.

Agharta seems like Davis’ mid-70s band delivering in near flawless form a distillation of what they had worked toward in the prior years. Everything is in its place, the band able to seamlessly do whatever the situation called for, and there is an orderly sense about it. One quality that makes Pangaea one of the Miles Davis albums I return to most often is that it is sort of the next possible phase. The music is full of suspicion. Yet it also does not rely on any sense of a guaranteed audience reaction, or even all the same array of songs Miles’ bands had been performing live for the past five years. The ground had been cleared and the period of desperate action was in place. Sure, Miles seemed to be continuing along the way he had been, but at the same time this was sort of a new look at the the same tools and structures. This is precisely why there are the slow interludes of “world music” with a thumb piano, etc. If Miles’ music in the 1970s had drawn from the likes of Sly & The Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix and James Brown, it is worth noting that all those artists had fallen away by 1975, no longer dominant forces. For that matter, the sort of black militancy that fueled this kind of music had been beaten back by the establishment, and in its place there was a growing accommodation to neoliberal tokenism. Instead of caving into that sense of decline, Miles’ music looked to encompass a more universal palette and to ally with other musics without diluting what it brought with. Critics hardly knew what to make of Miles in this era — just look at Lester Bangs‘ 1976 essay in Creem magazine “Kind of Grim: Unraveling the Miles Perplex.”

Miles’ band played a few more concerts in 1975, then he went into semi-retirement later that year, citing health problems. This is known as his silent period, when he barely left his house for years. He recorded only a few throwaway sessions until a comeback in 1980. The next live recording he released was We Want Miles in 1982. Some critics saw Miles’ entire fusion period as one of being a “sell-out”, and of pandering to commercial (rock) dictates. That position is somewhat astonishing. Perhaps it applies to Grover Washington, Jr. and others. But Miles? Bitches Brew was indeed a big hit. But everything that followed in the 1970s was not. What Miles did in the 1970s drew from European avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and stuck with a radically unprecedented musical approach far longer than seems possible, in hindsight. Miles’ retirement allowed him to preserve his integrity. When he made his comeback, he was all about accommodation, and his music reflected that. But pre-retirement, he just turned his back to the audience and kept on playing.

There are some who rate Pangaea much lower than Agharta, sometimes citing band fatigue due to being the later of two lengthy shows from the day (filling four LP sides). Another contingent places this ahead of Agharta, citing the more experimental, fluid and varied approach here. Either way, this is a great album that simply goes in a slightly different direction than Agharta. This album was influential on numerous punk rock figures, for instance. It remains an album of unique characteristics. It earns a place in the conversation for Miles’ (or anybody’s) best of the era.

![La Mort de Marat [The Death of Marat]](http://rocksalted.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Marat_assassinated.jpg)