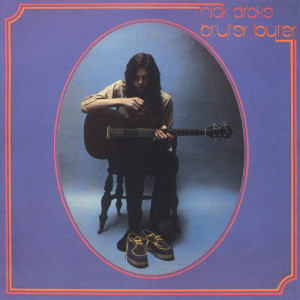

Nick Drake – Pink Moon Island ILPS 9184 (1972)

Nick Drake was an overlooked but extremely talented individual. Pink Moon is his most intense and ultimately best album. Sweet pop melodies and deep, intelligent songwriting are Drake’s trademarks. His refreshing approach moved far beyond simple love songs, with breathtaking but sad results.

The interaction between a man, his words, and his expression are profound. Gone are the lush strings and grand arrangements of his past work. Yet Pink Moon is incredibly expansive for just a singer with an acoustic guitar.

Where his previous release, Bryter Layter, looked towards better days ahead, Pink Moon begins by evaporating all hopes of happiness and grasps a bleak reality. The title track signals the break from his earlier work, and is the only track featuring piano. “Place to Be” then settles into blind depression. The brilliant guitar work on “Road” fills up space. While others may dream, Drake can only continue his static existence. He struggles just to understand his situation.

Drake is powerless to change himself or his world. On “Which Will,” he is a pawn held under someone else’s control. The instrumental “Horn” breathes a lingering sigh. He has not yet reached the point of acceptance. Side one ends with the cold observations of “Things Behind the Sun.” From a detached viewpoint, he collects thoughts and experiences.

Side two represents Nick Drake’s dawning awareness. “Know,” with just four lines of verse, evidences a new approach to life. The self-hypnosis of his guitar and chanting demonstrate his commitment to change. “Parasite” is one of the most gripping songs on the album. He finally opens his eyes wide and finds his place in a larger order. True to character, Drake portrays himself like an infection dragging failure to foreign places. Passing through a self-imposed exile, he sinks deeper into sin and despair. “Free Ride” is a plea for help, but “Harvest Breed” finds Drake freed to exist as an isolated oddity. He calmly stands in the face of his insecurities.

Concluding with “From the Morning,” Drake looks back on his travels. He takes his lessons on a final journey. His story ends in wry reflection. Nick Drake died a few years later, only 26, from an overdose of anti-depressants.

Pink Moon is a choreographed dance. A brilliant autobiography of genius, this was Nick Drake’s last gasp. Falling squarely between a comedy and a tragedy, in the classical sense, Pink Moon is ultimately an unassuming fragment of universal truth. It would be hard to say any other singer/songwriter ever produced such an immaculate album.