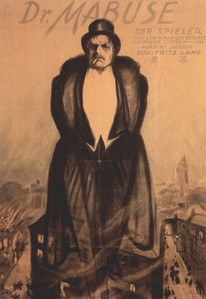

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler [Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler]

1. Teil: Der große Spieler: Ein Bild der Zeit [Part I: The Great Gambler: A Picture of the Time] (April 1922)

2. Teil: Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit [Part II: Inferno: A Game for the People of our Age] (May 1922)

Universum Film AG

Director: Fritz Lang

Main Cast: Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Bernhard Goetzke

In the spring of 1922, the first two films in the “Dr. Mabuse” series were released. Based on the novel Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1921) by Norbert Jacques (initially serialized in Berliner Illustrietren), with a screenplay adaptation by Thea von Harbou, the initial two films were released a month apart. In later releases, the two films tended to be presented together (and even confusingly identified as a single film). Over many decades, there were a dozen films and five novels made based on the Dr. Mabuse character — summarized and assessed in detail by David Kalat in his book The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse: A Study of the Twelve Films and Five Novels (2001). Although not particularly well known in the USA, the character was iconic in German popular culture. Jacques’ novel is said to have benefited from uncharacteristically large amounts of publicity, which contributed to it becoming an instant bestseller.

There has been an enduring misconception that the first film originally had a prologue with a montage of historical events of the Weimar Republic (in what is now Germany). However, Sara Hall has explained how this is erroneous because it attributes a prologue from a later Fritz Lang film, Spione (1926), to the first Dr. Mabuse film. Still, the Dr. Mabuse films did reflect many circumstances and general feelings of the Weimar era, if only allegorically or symbolically. Indeed, as Hall put it, the film “must be read as an allegory for the attempt to determine responsibility in the socio-political context . . . .” (“Trading Places: Dr. Mabuse and the Pleasure of Role Play,” German Quarterly, Vol. 76, No. 4 (Autumn 2003)). The subtitle of the first film/part was “A Picture of the Time” after all. A press flyer for the original theatrical release even claimed it depicted “the world in which we all live . . . , hovering between crisis and convalescence, leading somnambulistically just over the brink, in the search for a bridge that will lead [us] over the abyss . . . .” (as quoted by Stanford M. Lyman, “Cinematic Ideologies and Societal Dystopias in the United States, Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union: 1900-1996,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Spring,1997)).

Dr. Mabuse is a kind of supervillain. David Kalat described the character as “a criminal Führer who exploits social decay to his private advantage. Under a variety of disguises and assumed names, he has broken free of the traditional class divisions and invaded the previously insulated enclaves of the decadent upper class.” Norbert Jacques’ inspirations for Dr. Mabuse — or at least tacit precedents — were villains such as Svengali, Dr. Fu Manchu, Doctor Nikola, Fantômas, and even Dr. Caligari. Dr. Mabuse is — simultaneously — a practicing psychoanalyst with powers of telepathic hypnotism, a leader of a large criminal organization (that engages in stock market destabilization, counterfeiting, and also dupes wealthy gamblers in clandestine casinos), and a master of disguise. In many ways, the character of Dr. Mabuse is a kind of stand-in for all the perceived social evils of the Weimar era that led to generalized feelings of anxiety and fear. On close inspection, he is a pastiche of frequently contradictory elements that suggest a politically populist conception. Strangely, many of the academic studies on the films do not make an explicit populist reading of the character or film as a whole (or do so without articulating the term “populism”), and some also casually rely on a number of all too familiar ahistorical tropes.

An online encyclopedia summarizes a few views on the Mabuse character this way:

“[Director Fritz] Lang stated that he viewed Mabuse as a Nietzschean Übermensch.[6] Lang also saw Mabuse’s character as emblematic of a certain kind of money-accumulator in Weimar Germany referred to as a ‘Raffke’.[3] The producer of Dr. Mabuse, Erich Pommer, saw the film as a depiction of the contemporary conflict between the liberal conservatives and the Marxist Spartacists in which the Mabuse character represented the Spartacists.[3]“

Perhaps the most dominant view of the Dr. Mabuse character comes from Frankfurt School theorist Seigfried Kracauer‘s influential book From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947), which contended that Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler reflects society under a tyrannical regime and that the character Dr. Mabuse fit in a procession of tyrants. Kracauer and others have seen Dr. Mabuse as a sort of precursor to the rise of Hitler. But, at the same time, Dr. Mabuse is not simply synonymous with Hitler, who rose to power only years later.

By portraying Dr. Mabuse as a psychoanalyst, the film associates him with a (then still rather new and emerging) discipline that connoted Jewish practitioners as well as communists. His Couéian hypnotic powers are an exaggeration and unrealistic portrayal of psychoanalysis, even in its early (pre-Lacan) days. Mabuse’s tendency to attack the rich, whether by hypnotizing them to lose or cheat in illicit card games, sometimes with no monetary benefit to himself, or by causing stock market runs, is also a curious character trait. These traits all seem to potentially associate Dr. Mabuse with some political leftish position, however vague and inchoate. The producer of the film, Erich Pommer, even explicitly associated him with the communist Spartacist League, which is a somewhat obscene misrepresentation of the Spartacists’ aims and methods.

On the other hand, the tyrannical “will to power” that Dr. Mabuse puts forward, quite explicitly at the end of the first film, is very much a part of the Nietzschean “Übermensch” mentality that was adopted by the Nazis (Nationalsozialismus [National Socialists]) in the coming years. Peter Sloterdijk has also commented on how the Weimar Era had a Napoleonic tendency — Emil Ludwig‘s biography Napoleon (1925) was another of the most widely read books in the Weimar Republic. Mabuse’s criminal kidnappings and destabilizations of society also mirror proto-fascist actions of the era, such as the Kapp Putsch, the murder of centrist liberal Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau a mere month after the premier of the second film (historians say “Germany’s anti-semitic nationalists . . . saw in Rathenau, not a great patriot brilliantly managing scarcity, but a rich Jew cornering markets”), the later Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, and generalized financial and business opportunism by a host of individuals seeking to enrich themselves in predatory ways. All these elements associate the character with the political right, and fascists in particular. The benefit of hindsight reinforces these perspectives somewhat, especially in view of Lang’s (excellent) follow-up film Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse [The Testament of Dr. Mabuse] (1933), which aligns the Dr. Mabuse character’s overall story arc with that of Hitler more closely — to the point that the Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels banned it.

But Dr. Mabuse is, strangely, all of these things at the same time in the first two films. Indeed, Erik Butler has noted that the character is a paradox, though without convincingly explaining why. (“Dr. Mabuse: Terror and Deception of the Image,” The German Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 4 2005). What unites these seeming opposed and mutually exclusive traits is the notion that a single individual is somehow capable of it all and that ordinary German people of the day were subject to all of those various threats posed by Dr. Mabuse. This is precisely the populist foundation of the films.

Slavoj Žižek wrote about populism in his book In Defense of Lost Causes (2008):

“Populism is ultimately always sustained by ordinary people’s frustrated exasperation, by a cry of ‘I don’t know what’s going on, I just know I’ve had enough of it! It can’t go on! It must stop!’ — an impatient outburst, a refusal to understand, exasperation at complexity, and the ensuing conviction that there must be somebody responsible for all the mess, which is why an agent who is behind the scenes and explains it all is required. Therein, in this refusal-to-know, resides the properly fetishistic dimension of populism.” (p. 282)

***

“for a populist, the cause of the troubles is ultimately never the system as such but the intruder who corrupted it (financial manipulators, not necessarily capitalists [as a class], and so on); not a fatal flaw inscribed into the structure as such but an element that doesn’t play its role within the structure properly. For a Marxist, on the contrary (as for a Freudian), the pathological (deviating misbehavior of some elements) is the symptom of the normal, an indicator of what is wrong in the very structure that is threatened with ‘pathological’ outbursts. For Marx, economic crises are the key to understanding the ‘normal’ functioning of capitalism; for Freud, the pathological phenomena such as hysterical outbursts provide the key to the constitution (and hidden antagonisms that sustain the functioning) of a ‘normal’ subject.” (p. 279)

Žižek has discussed this conception of populism elsewhere too, in ways that draw out other aspects relevant to the Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler films and the subsequent rise of fascism in Germany — all sharing a glorification of persecution narratives that have long been referred to as scapegoating. These analyses critique the theories of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, the most well-known latter-day proponents of populist political theory. Žižek specifically identifies fascism as a form of populism.

“This is also why Fascism definitely is a populism: its figure of the Jew is the equivalential point of the series of (heterogeneous, inconsistent even) threats experienced by individuals: Jew is simultaneously too intellectual, dirty, sexually voracious, too hard-working, financial exploiter…

***

“In populism proper, this ‘abstract’ character is furthermore always supplemented by the pseudo-concreteness of the figure that is selected as THE enemy, the singular agent behind all the threats to the people.”

“Against the Populist Temptation” Critical Inquiry 32 (Spring 2006).

“Fascism itself is immanently fetishist: it needs a figure like that of a Jew, elevated into the external cause of our troubles – such a figure enables us to obfuscate the real antagonisms which cut across our societies.

“Exactly the same holds for the figure of ‘fascist’ in today’s liberal imagination: it enables people to obfuscate deadlocks which lie at the root of our crisis.”

“Today’s Anti-fascist Movement Will Do Nothing to Get Rid of Right-wing Populism – It’s Just Panicky Posturing”, The Independent, December 2017; see also and “Big Capital Will Use Every Tool at Its Disposal to Crush Socialists Like Corbyn”, RT, December 2019 (“anti-Semitism is a displaced anti-capitalism: it projects the cause of social antagonisms engendered by capitalism onto an external intruder (the ‘Jews’).”).

“As with fascism, . . . populism is simply a new way to imagine capitalism without its harder edges; a capitalism without its socially disruptive effects.”

“Are Liberals and Populists Just Searching for a New Master?” The Economist: Open Future (Oct. 8, 2018).

These comments are similar to things that Jean-Paul Sartre wrote about just after WWII:

“I would call anti-Semitism a poor man’s snobbery. And in fact it would appear that the rich for the most part exploit this passion for their own uses . . . . *** Incapable of understanding modern social organization, [the anti-semite] has a nostalgia for periods of crisis in which the primitive community will suddenly reappear and attain its temperature of fusion. He wants his personality to melt suddenly into the group and be carried away by the collective torrent. *** [Anti-semitism] represents, therefore, a safety valve for the owning classes, who encourage it and thus substitute for a dangerous hate against their regime a beneficent hate against particular people.“

Réflexions sur la question juive [The Anti-Semite and the Jew] (1947).

Of course, there are variations on populism. Fascism obviously sits at the extreme political right wing of that spectrum. Though variations reside elsewhere too. Even Dr. Mabuse’s description in the film’s subtitle, as “the gambler” (albeit a cheating one), prefigures use of the term “casino capitalism” in a classically populist if centrist/”progressive” way to denote a deviation from properly functioning capitalism without looking at the internal contradictions of capitalism as a whole (though the term “der Spieler” can also be translated as player, actor, or performer [Cassell’s German Dictionary 1978]). Sloterdijk (in a book chapter entitled “On the German Republic of Imposters”) has characterized the Weimar Republic as having a will to be deceived, and a fascination with a certain con man’s element of Napoleonism (“the factors of seduction and drama, of diplomacy and cynical flight into false candidness”) and a reliance on the “ironic gambler’s nature of Napoleonic realism” (“that capacity of hard egos to withstand the failure of their plans and hopes”), saying, “[f]raud and expectations of fraud became epidemic in it” and that “the imposter became an indispensable figure in the sense of collective self-reassurance, a model of the times and a mythical template.” But as Éric Fassin has explained, the crux of populism, of any flavor, is what the French have long identified as ressentiment — “the idea that there are others enjoying what is mine, [and that] if I am not enjoying it, this is because of them” — and he further claims that there is really no such thing as good left populism. (Populisme: le grand ressentiment (2017)). That is, any populism contains the expression of “impotent rage” against undeserving others that constitutes its own form of “enjoyment.” This is precisely what Žižek identified as the fetishistic dimension of populism, because “the true opposite of egotist self-love is not altruism, concern for common Good, but envy, resentment, which makes me act AGAINST my own interests.”

Sarah Hall reached a different conclusion when looking for a similar basis for audience enjoyment of Dr. Mabuse, suggesting that enjoyment of “role play” was the explanation. She concluded that the film “allow[s] its spectator to understand and experience identity and subjectivity as multiplicity, layering, and performance.” Hall posited that the audience’s inquisitiveness and willingness to confidently guess at Dr. Mabuse’s identity as the film obscures it are a source of pleasure that drives interest in the film. While Hall’s analysis also looks at an audience’s desire or source of pleasure as an important topic for critical analysis, implicitly drawing from psychoanalysis, it essentially reaches the opposite conclusion from the present “populist” analysis. In the “populist” view the audience derives pleasure from sharing in the film’s refusal to know (or at least its complicity in maintaining a state of not knowing), whereas Hall see the audience as instead deriving pleasure from its attempts to know through experience. But Hall’s approach is ultimately unconvincing due to its emphasis on conscious identity and identification (especially gender) that is grafted on to an analysis of pleasure and desire in an ill-fitting way. She looks for signifiers but ultimately bases her analysis on the assumption that audiences want (and can obtain) satisfaction of their desires by matching symbolic norms to historical contingencies, rather than having a reflexive desire to desire (that is, mediated desire based on what they believe an “other” lacks or desires without conclusively knowing the other’s desire) that strives for recognition as part of a constant process of questioning (per Lacan). She also assumes that audiences identify with characters in the film, driven to personally assume the identities of the characters in the film rather than simply wishing to see the characters resolve the tensions presented in the film amongst themselves or between their inner desire and outward events as a matter of innately shared (rather than view-adopted) audience-character desire. There is a kind of hollowness to her analysis — this reviewer did, or at least was tempted to, fast forward through a few scenes that seemed trite that Hall describes as key examples of her theory (this is anecdotal, sure, but how can the basis for the fundamental appeal of the film be something that this viewer had no interest in, even though this viewer was indeed very interested in the film?). In a nutshell, Hall tries to take a psychoanalytic analysis through the historicism of Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Laura Mulvey, etc. (Hall cites Butler explicitly) and anyone familiar with Lacanian psychoanalysis will wince, or at least disagree at some level. The Lacanian critique is “yes, psychic sexual identity is a choice, not a biological fact, but it is not a conscious choice that the subject can playfully repeat and transform. It is an unconscious choice which precedes subjective constitution . . . .” Alenka Zupančič has detailed how really there is a fundamental negativity, that is, a gap or lack, that structures the very space of this (and all) performative (identity) activity, and that is constitutive of the discourses and surplus enjoyment that appear in that gap that are really ways of dealing with antagonism and the impossibility of rationalizing or eliminating that fundamental, constitutive negativity. Hall proceeds from an opposite premise. Despite quite rightly naming gender as a performative choice (that is, a symbolic social construct), she first presupposes the positive existence of various performative “roles” (that is, assuming their immanence) and then essentially trivializes the role of the unconscious as a factor reflexively limiting and biasing conscious choice (that is, Hall renders such roles exclusively as stable, preexisting symbolic social constructs). In other words, contrary to Hall’s presuppositions, this is really a forced choice, and that forced choice is a way of dealing with a negativity or antagonism that structures and biases the very choices available, with these things being fundamental to establishing a person’s subjectivity and not a secondary matter that follows after the establishment of subjectivity. Hall’s approach is in a way a maneuver quite akin to the voluntarist neoliberal ideology that emphasizes individual entrepreneurship and market success as a cure to poverty (or as a key to success) by ignoring inhibitors like core/periphery geography, racism, contested labor relations, and the like by focusing only on symptoms of class relations without addressing the core of class relations that establishes the entire social field that generates those symptoms. That is to say, as Zupančič put it, it relies on the ideology of the free market to cover up and perpetuate underlying antagonisms and is a very dubious line. Joan Copjec’s work is one place to start for a rebuttal of the Foucault/Bulter framework that Hall relies upon, though the work of others like Daniel Zamora also helpfully elaborates the politically neoliberal character of Foucault/Bulter’s theories and Todd McGowan‘s work is also useful particularly in the context of film studies by explaining how an audience’s desire is already taken into account by the very visual field of a film.

If we instead look at the Lacanian subject as being conceived as a lack, gap, or void (with the subject realized by links forged between signifiers in a chain that is excluded from consciousness, reflexively caused by the “other’s” desire), the “playing with identity” inquiry that Hall posits leads somewhere else. What if instead the Dr. Mabuse film exposes that the constructed identities of Dr. Mabuse are all performative and that there is nothing to him underneath that precedes those constructed identities, and that all his attempts to present another appearance, despite his seeming superpowers, fail? That is to say, what if all his disguises are performances that are unable to construct or maintain a “true” underlying identity (subject) such that when he is finally cornered by the police and military he goes “insane” (hystericized?) because of the trauma of confronting his own subjective constitution, with an unconscious structured as a void that lacks any positive content? This would make his pursuer, Prosecutor (Staatsanwalt) von Wenk, somewhat like an analyst trying to intervene in the real of Dr. Mabuse’s unconscious, beyond his symbolic identities (disguises). This would also make the film about a very tentative discourse of the hysteric, which stops once Dr. Mabuse’s disguises are breached and he is identified by the prosecutor (who does nothing to really draw out the cause of Mabuse’s actions as a thoroughgoing discourse of the analyst would but instead demands that Mabuse reveal his identify and give up his claims to being a master outside the law). For instance, when he is trapped, Mabuse is confronted with specters of dead gang members calling him a cheater as von Wenk closes in. The audience might interpret the scene as Mabuse’s own discourse of the master crumbling when the ghosts of his deceased henchmen no longer recognize him as a master and his criminal syndicate no longer functions. Once Mabuse’s master discourse falls apart, the dynamics of the film return to a dominant populist discourse of the university for which the master-signifier is the Weimar Republic’s structural economic conditions — with von Wenk representing a rationalization of those reigning (liberal capitalist) economic conditions as the master-signifier, positing the (false) symmetry that everything would be fine — and the junkers free to continue their decadent lifestyles of the idle rich — if merely “law and order” prevails over Mabuse’s deceptive and intrusive criminality. That is to say, the discourse of the hysteric is compartmentalized between von Wenk and Mabuse, and is never directed at von Wenk too. That very compartmentalization is peculiar in that Dr. Mabuse’s use of multiple disguises is, from a certain perspective, an effort at constructing liberal pluralism at a most basic level in the form of the very notion of a society as a grouping of disparate but equal individual identities held together and mediated by a neutral and reasonable state, and thus also an effort constitutive of the putative liberal-pluralistic basis for the Weimar Republic that the film reveals, instead, to be a fundamental (political) contradiction or antagonism that the likes of von Wenk disavow or rationalize through the application of technocratic legal means that single out Mabuse as a deviation rather than a symptom. The primacy of populist university discourse might also explain why, toward the end of the second film, Dr. Mabuse seems more interested in defeating or outwitting Prosecutor von Wenk than in any other goal, thus avoiding any further discourse of the hysteric or resolution of the failure of his own discourse of the master. Though if you watch Lang’s next film, Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse [The Testament of Dr. Mabuse], you see Dr. Mabuse reconstitute a Hitler-like discourse of the master after the trauma of the original films’ conclusion. In short, there are competing discourses battling for supremacy, with the films’ audience pushed or drawn toward a populist university discourse when all is said and done. The audience’s (presupposed) drive is to repeat the loss of an explanation, so that that the easing of tension produced by the many bogus explanations for miserable real-life conditions in the Weimar era posited by Dr. Mabuse’s many disguises can be repeated over and over. It is the trauma of the Weimar era that set all this in motion — and the trauma of the miserable real-life conditions of the neoliberal era nearly a century later might be analogous.

But what about alternative political frameworks to the present populist frame? Many commentaries that merely cast the character of Dr. Mabuse as a “totalitarian” risk the sort of reductionist blackmail that Ernst Nolte‘s conservative historical revisionism promoted, similar to so-called “horseshoe theory” that posits two and only two political options: western (conservative) liberalism or totalitarianism (both left and right).

[Ernst] Nolte’s idea is that Communism and Nazism share the same totalitarian form, and the difference between them consists only in the difference between the empirical agents which fill their respective structural roles (‘Jews’ instead of ‘class enemy’). The usual liberal reaction to Nolte is that he relativises Nazism, reducing it to a secondary echo of the Communist evil. However, even if we leave aside the unhelpful comparison between Communism – a thwarted attempt at liberation – and the radical evil of Nazism, we should still concede Nolte’s central point. Nazism was effectively a reaction to the Communist threat; it did effectively replace class struggle with the struggle between Aryans and Jews. What we are dealing with here is displacement in the Freudian sense of the term (Verschiebung): Nazism displaces class struggle onto racial struggle and in doing so obfuscates its true nature. What changes in the passage from Communism to Nazism is a matter of form, and it is in this that the Nazi ideological mystification resides: the political struggle is naturalised as racial conflict, the class antagonism inherent in the social structure reduced to the invasion of a foreign (Jewish) body which disturbs the harmony of the Aryan community. It is not, as Nolte claims, that there is in both cases the same formal antagonistic structure, but that the place of the enemy is filled by a different element (class, race). Class antagonism, unlike racial difference and conflict, is absolutely inherent to and constitutive of the social field; Fascism displaces this essential antagonism.

“The Two Totalitarianisms” London Review of Books, Vol. 27, No. 6 (March 17, 2005). Here we can see that such a reductionist move ends up in a troubling pro-fascist position (or engages in fascist apologetics), turning Dr. Mabuse from a villain into a hero. Any such views must be called out on this basis, even if it is possible to say that Dr. Mabuse attacks a social order that denies its own depravity and self-destructive tendencies.

David Kalat’s The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse draws parallels between Dr. Mabuse and the French fictional character of Fantômas, who was launched in 1911 and was popular in surrealist circles with anarchist sympathies as a kind of anti-hero who waged war against bourgeois culture. There are important common elements between these characters, including both being a master of disguise, inflicting terror, and having a nemesis in the police. Even the publicity poster for Dr. Mabuse (reproduced above) showed the title character in a tuxedo and top hat towering over a city much like the iconic attire of Fantômas. The key difference is perhaps that Mabuse and his gang engaged in criminal actions that ordinary German viewers would have seen as having effects on themselves and their entire society, such as through inflation and price fluctuations, whereas Fantômas engaged in more individualized escapades that focused more narrowly on the rich. An anarchist reading of Dr. Mabuse is not really satisfactory, though, and the anti-rich sentiments based on “vertical” opposition between the powerful and the lowly masses that seemed to drive some readers’ interest in Fantômas might be equally said to be populist. Anyway, an anarchist reading is not really developed by Kalat, though others like Kracauer, Bernd Widdig, and Norbert Grob have made more substantive assertions. But Martin Blumenthal-Barby has questioned such a reading on the grounds that Dr. Mabuse is quite consciously and purposefully at the top of the hierarchy of his criminal organization that he relies upon to carry out most of his plots on his behalf, which is contrary to basic anarchist principles. (“Faces of Evil: Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler,” Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Sept. 2013)). Indeed, when Dr. Mabuse declares in the film, “I want to become a giant . . . churning up laws and gods like withered leaves!!” this aspiration to be a “giant” is simply not an anarchistic goal. It is more a Napoleonic if slightly nihilistic claim to power, merely displacing others who currently hold it. Likewise, when Dr. Mabuse declares that he is like a “state within a state” this also runs against prevailing anti-statist strains of anarchism. It isn’t even Blanquism or an explosion of pure negativity/negation.

All this suggests that “populism” in its precise theoretical sense is the most informative frame in which to view these films. Such a populist lens allows viewers to grasp the contradictory aspects of the Mabuse character, which also elucidates the appeal of the (overly) simplistic explanations of social antagonisms it offers viewers. Mabuse was, in this sense, the result of the structural contradictions of Weimar society, though as a supervillain he is cast as the cause rather an effect. But is there any empirical support in the historical record for the notion that the Mabuse character was a simplification that transposed cause and effect? Actually, yes. This can be seen by looking at the particular case of hyperinflation and currency exchange issues that are quite explicit in the plot of the initial Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler films — for instance, Mabuse’s gang has a counterfeiting facility and throughout the movies characters pause to inspect paper money.

The economist Michael Hudson wrote his landmark book Super Imperialism: The Economic Strategy of American Empire (1972) in the early 1970s. It included an in-depth discussion, drawn from the earlier work of John Maynard Keynes, Salomon Flink’s The Reichsbank and Economic Germany (1930), and other sources, that showed how Weimar Germany’s economic conditions were intimately tied to the conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles (David Kalat’s The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse mentions these conditions in a section on the historical backdrop for the Mabuse films). Peter Sloterdijk, too, has written that “[t]he Weimar peace became a continuation of war through other means[,]” further noting that the Treaty of Versailles “represents the earth-shattering diplomatic mistake of the century.” Hudson later summarized these conditions in a 2012 presentation:

What is remarkable is that awareness of the empirically valid side of the 1920s German reparations debate has disappeared from today’s discussion. The losers in that debate – the austerity advocates – have swamped the popular media, government and even the universities . . . . The German public has been given a false memory of its traumatic hyperinflation. The pretense is that this resulted from the Reichsbank financing domestic currency spending. The true explanation is to be found in the foreign currency collapse – trying to pay foreign debts far beyond the ability to do so.

***

In 1919 the Allies imposed unpayably high reparations on Germany – largely to pay the Inter-Ally arms debts that the U.S. Government insisted on collecting from Britain and France for supplies and weapons sold before the United States entered the war. Such debts traditionally were forgiven among allies upon achieving victory. But the U.S. Government refused to do this, so its wartime customers turned to Germany to pay.

Its liability was unlimited under the Treaty of Versailles. For starters, Germany was stripped of its coal reserves, steel mills and other valuable assets. This left little alternative but for the Reichsbank to create German marks to throw onto the currency markets to obtain the foreign exchange to pay reparations. This raised the price of imports, and hence the domestic price level. More money was needed to transact purchases and sales at the higher price level. So the line of causation went from the balance of payments and currency depreciation to rising import prices. More expensive imported goods raised domestic prices as well. It was this that created a need for a higher money supply, not domestic money that forced higher prices.

Without denying that currency speculators — Raffke — were active at the time, this shows how attributing economic ills to a single supervillain, even as a composite stand-in for a group of currency manipulators, etc., obfuscates the empirically-supported historical causes that were tied to international geopolitics — especially American intransigence and greed and the acceptance of that posture at the very foundations of the Weimar Republic. More generally, historians note that “most Germans were furious about the Treaty of Versailles, calling it a Diktat (dictated peace) and condemning the German representatives who signed it as ‘November criminals’ who had stabbed them in the back . . . .” Ordinary Germans lacked any ability to meaningfully intervene in such global machinations to maintain their standard of living, fostering resentment. There were faced with a systemic deadlock. And there is of course a transposition in that the “Übermensch” of Dr. Mabuse is portrayed as a bad guy not a savior (master) like Hitler later presented himself. This is not to fault Fritz Lang and the writers for failing to predict the future and accurately foresee the exact contours of the later rise of Hitler — and failing to convey that rather literally in the film. Rather, this film’s strength is its more general depiction of the populist temptation (later seized upon by the Nazis) to envy, demonize, and scapegoat an “other” rather than understand the contradictions inherent in the (capitalist) Weimar Republic and engage those contradictions in a meaningful resolution.

Tacitly fitting with this populist reading are Anton Kaes‘ observations about the film, which echo comments about the fetishistic need for collective, mythical self-reassurance:

“Dr. Mabuse commented on the social and cultural turmoil of the immediate postwar years. *** [H]ypnotism and the occult are used to convey a pervasive sense of manipulation and powerlessness. *** [P]redator fantasies articulate . . . vague fears . . . . *** Dr. Mabuse propose[s] that ruthless but invisible forces are at work, thus obscuring the concrete causes and effects of the lost war. *** Dr. Mabuse reveal[ed] a . . . society in search of an enemy who can be blamed for the defeat.”

Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War (2009).

Martin Blumenthal-Barby noted something similar when he questioned “accounts for the evil threat ‘Mabuse’ as an extraneous force that appears to attack and corrupt humankind from the outside and, as such, one might assume, can also be overcome as a result of a modification of these extraneous conditions.” (“Faces of Evil,” supra). (Though Blumenthal-Barby seems wrong in taking the position that Kaes’ seemingly populist reading is at odds with Kracauer’s fascist reading, if we consider fascism a type of populism). In other words, the details of this fictional story should not be judged for how they do or do not match up against specific historical events stretching into the future. It is more useful to look at the possible larger, theoretical meaning it presents to viewers. This appropriately echoes the scene in the first film when the character Count Told asks Dr. Mabuse what his thoughts are on expressionism — a debate taken up by Ernst Bloch and others in the 1930s.

An interesting approach here is to apply the common paraphrase of a concept explored by Walter Benjamin (and others): behind every fascism lies a failed revolution. The Spartacist League attempted an unsuccessful revolution in Weimar Germany in January of 1919 aimed at resolving the underlying internal contradictions of its socioeconomic structure (as a part of the western capitalist world system), and, in their failure, the fascists of the Nazi party deployed a type of populism that blamed Jewish people (and communists, etc.) as the external cause of all socioeconomic problems. The essential feature here is that the liberal centrists of the Weimar Republic were not addressing or resolving socioeconomic problems that affected ordinary citizens who desired a stable economy, and the liberal centrists were perhaps in denial about them, leaving a choice between the political left or the political right. When the leftist Spartacists were defeated (and two of its leaders, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, murdered), and the Bavarian Soviet Republic overthrown (after Kurt Eisner was assassinated), there was seemingly no option remaining but the rise of the Nazis to provide the “bridge that will lead [us] over the abyss” that the Dr. Mabuse press release suggested audiences were looking for. Despicable and repugnant as they were, the Nazis did speak to the desires of ordinary Germans, much like Ronald Reagan did in the 1980s United States. Drawing from Fredric Jameson, Žižek noted:

“To take the worst imaginable case, was Nazi anti-Semitism not grounded in the utopian longing for an authentic community life, in the fully justified rejection of the irrationality of capitalist exploitation? Our point, again, is that it is theoretically and politically wrong to denounce this longing as a ‘totalitarian fantasy’, that is, to search in it for the ‘roots’ of fascism—the standard mistake of the liberal-individualist critique of fascism: what makes it ‘ideological’ is its articulation, the way this longing is made to function as the legitimization of a very specific notion of what capitalist exploitation is (the result of Jewish influence, of the predominance of financial over ‘productive’ capital—only the latter tends towards a harmonious ‘partnership’ with workers) and of how we are to overcome it (by getting rid of the Jews).”

“Multiculturalism, or, the Cultural Logic of Multinational Capitalism,” New Left Review 225 (Sept./Oct. 1997).

It was the absence of an alternative to Nazi responses to the desires of ordinary people that is the key to Benjamin’s great insight. Here, something Žižek wrote nearly a century after the film’s debut equally applies, in the way that Prosecutor von Wenk’s character refuses to admit (or even contemplate) that the society he sees as disappearing in the face of Mabuse’s crimes was already irretrievably lost: “the only way to really defeat populists and to redeem what is worth saving in liberal democracy is to perform a sectarian split from liberal democracy’s main corpse.” Žižek instead suggests a need to “radicalise one’s position.” In some ways, Alfred Döblin‘s later novel, Berlin-Alexanderplatz (1929), is a more astute and nuanced fictional depiction of this dynamic from the films regarding a lack of an alternative to fascism — though it was written with the benefit of a few more years of experience of rising fascism in the Weimar Republic. But Berlin Alexanderplatz has a more subdued, intimate tone than the frequently fast-paced and intensely confrontational scenes in the Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler films.

Fritz Lang was definitely a modernist. But Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler is an early work of modernism — a poster for a Russian release in the supremacist style was even designed by Kazimir Malevich! Looking back on it a hundred years later, critics and audiences are right to point out that the pacing sometimes feels a bit odd and disjointed and the camera framing is a bit theatrical and old fashioned. But even if modernism later evolved and developed new and more effective techniques, this Lang film was in a large part responsible for spurring such continued efforts. Lang’s more concrete innovations here are found in broader editing and montage techniques and the integration of special effects, action, and art deco interior and expressionist exterior sets into a story to highlight political aspects of the script. All this is to say that the film subtly offers exaggerated depictions in order to probe realistic concepts. Take the thrilling standoff between the police/military and Dr. Mabuse gang. Rather unrealistically, a mere handful of gang members manage to hold off the advance of the police later augmented by a troop of soldiers, inflicting heavy casualties. Because of the deferred confrontation between Dr. Mabuse and Prosecutor von Wenk, the shootout is exciting even as its staging and plot contours are mostly ridiculous — though, from the Lacanian perspective, perhaps it is even a bit like the absurd fight scene in John Carpenter‘s They Live (1988) as one character seeks to avoid putting on sunglasses that allow people to see the world as it really is (free of alien influence). On the other hand, the stylized, fabulist depictions of Dr. Mabuse’s hypnotic powers often rely on special effects like text overlays that create a sense of how characters are influenced but also divert attention from the improbably unrealistic portrayals of the very existence of these mystical powers in the first place. Audiences are apparently meant to just accept that these powers of telepathic hypnotism are indeed supernatural. Though the use of superimposed images that portray a person as an apparition or superimposed spirit are highly effective in conveying eerie influences on characters, without having to rely on the conceit of supernatural hypnotism.

For a good online review summarizing events in mostly the first film, see “Organised crimes… Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), BFI Weimar Cinema Season.” Otherwise, David Kalat’s book The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse is the single best resource on the film, as well as the entire “Dr. Mabuse” book and film series.

Anyone fascinated by Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler might want to also view Charlie Chaplin‘s overlooked Brechtian “talkie” Monsieur Verdoux (1947). This later Chaplin film is also set in the 1920s, and features an imposter involved in stock market activities who is pursued by the police. Chaplin’s film, in contrast though, lacks a populist element and instead invokes a class-based analysis that depicts what happens when someone from the working class attempts to live as one of the bourgeoisie — emphasizing how different sets of rules are created and applied to different social classes.

Day of the Dead

Day of the Dead