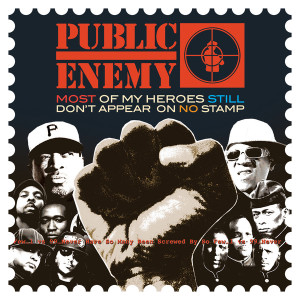

Public Enemy – Most of My Heroes Still Don’t Appear on No Stamp Enemy Records ERSD002LC (2012)

It would be easy to write off Public Enemy as a hip-hop group long past its time of relevance, but that would be a mistake. Most of My Heroes Still Don’t Appear on No Stamp, released in the group’s third decade (and 25 years after their debut album), is about as relevant as anything in hip hop. There is only one dud (“Rltk”). The rest might not feature anything as powerfully catchy as their biggest hits of their early days. Still, the simple, utilitarian beats get the job done. The group isn’t innovating when it comes to beats — if anything, they are looking backwards somewhat, more so than on The Evil Empire of Everything released the same summer. Yet these are the sorts of beats that made hip-hop what it is, providing a hardness that provides momentum, and most importantly are ones that fit the talents of the MCs and the message they have to offer. Chuck D is still one of the smartest and most compelling lyricists in the genre. On “Truth Decay” he raps, “The truth dies while lies make a living.” And on “”I Shall Not Be Moved” he goes on about the “senior circuit” in a funny way. Sure, it might help if he (and the rest of PE) was a little more of a feminist and less prone to advocate for the Nation of Islam, but those are petty quibbles. On the interludes that talk about “heroes” that should be on stamps, as referenced in the album title (which quotes a lyric from their iconic 1989 song “Fight the Power”), that statement has to be qualified quite a bit. Without speaking for S1W James Bomb, who wrote and performs the spoken parts, he has to concede that Malcolm X was on a U.S. stamp issued in 1999 (Chuck D cites Malcolm X as a hero on some notes to the album). When Elijah Muhammad is mentioned on “…Don’t Appear on No Stamps (Part I)” as “one of the great ones,” well, it is hard to agree agree — Elijah Muhammad deserves that honor as much as Richard Nixon, which is to say not at all. But this is really the wrong way to look at the album title, and the interludes of the same name. The point is that there are a lot of heroes out there and they aren’t all celebrities. Chuck D raps, “To some of my heroes/ be most of y’all’s foes,” going on to mention “Belafontes to Bikos / some dying incognegro / Che, Chávezes and Castros.” Flavor Flav name-checks Huey P. Newton, H. Rap Brown, Marcus Garvey, Angela Davis, C. Delores Tucker, Cynthia McKinney. And those are just a few. Harvey Milk, John Brown, Leonard Peltier, Subcomandante Marcos and others are mentioned too.

Future president Jimmy Carter gave a speech to a room full of lawyers on “law day” (an occasion created as a rebuttal to the international workers holiday May Day) in 1974 where he sharply criticized what lawyers do, and how they resisted Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s reforms, and concluded by discussing Leo Tolstoy‘s novel War and Peace:

“And the point of the book is that the course of human events, even the greatest historical events, are not determined by the leaders of a nation or a state, like Presidents or governors or senators. They are controlled by the combined wisdom and courage and commitment and discernment and unselfishness and compassion and love and idealism of the common ordinary people.”

Public Enemy is saying something similar. They are all over the Occupy Wall Street slogan the 1% vs. the 99%. As they put it, “Never have so many been screwed by so few.” As Chuck D said, “While I like artists like JAYZ and KANYE WEST and consider them giants who are afforded to project their opinion through culture, Its been difficult for me to like and respect their viewpoint in theses times. . I must fight for the balanced art projection of the real side of life as opposed to the fantasy world which most likely cannot be attained by many.” The liner notes to the album, too, are a history of PE’s efforts to use alternative and independent media, and to escape the clutches of greedy entertainment corporations.

It is great that PE is still around, still making music, and just as committed as ever — maybe more so — to making music that matters. The group’s heart is in the right place, and just as often their heads and fists are in the right place too.