Link to a review of the Paul Mason book Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future (2015) by Jacob Hjortsberg:

Category: Books

Stanisław Lem – Solaris

Stanisław Lem – Solaris (MON 1961)

A work of science fiction, yes, but Solaris is also as much about humanity as anything else. Psychologist Kris Kelvin travels to a space station on the planet Solaris, where strange things have been happening. The thoughts of the cosmonauts are made corporeal, as “visitors”, by the planet itself. A kind of pink slime “ocean” covers the planet. It is sentient. The ocean is even able to adjust the planet’s orbit between two suns. A fascinating (and horrifyingly realistic) subplot is the way that Kelvin uncovers a conscious/unconscious plot by scientists to suppress the nature of the planet in published reports, relegating certain information to an Apocrypha and discrediting those whose findings contradict official dogma, with scientists acting like the guardians of religious institutions rather than seekers of knowledge as they profess to be. The scientists are only able to apply language that is internally consistent, like mathematics, but never explains the mystery of the planet itself. The planet remains an impenetrable other, its motivations inscrutable and unknown to the scientists. Is it experimenting on the scientists? Is it trying to help them? No one knows. Comparing the novel to Moby Dick, Lem said that he “only wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that certainly exists, in a mighty manner perhaps, but cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images.” But what dominates the story about scientists who cannot hope to understand the planet Solaris, is that they also fail to understand themselves. Everything they experience about the planet is filtered through their own, flawed consciousnesses first. The premise of the book maps directly onto the work of Jacques Lacan, Alain Badiou, and continental philosophy — Lem called the Freudian interpretation “obvious”. Certainly, one of the greatest of 20th Century Sci-Fi novels.

Staughton Lynd – Anarchism, Marxism and Victor Serge

Link to a book review by Staughton Lynd:

Bouree Lam – Why “Do What You Love” Is Pernicious Advice

Link to an interview with Miya Tokumitsu, author of Do What You Love: And Other Lies About Success and Happiness (2015), by Bouree Lam:

“Why ‘Do What You Love’ Is Pernicious Advice”

Bonus links: “Forced to Love the Grind” and “Žižek!” and The End of Dissatisfaction?: Jacques Lacan and the Emerging Society of Enjoyment

Ursula K. Le Guin – The Dispossessed

Ursula K. Le Guin – The Dispossessed (Harper & Row 1974)

In the tradition of leftist utopian novels, often there is a tendency to make story and plot secondary to gratuitous description and monologues. The bestselling Looking Backward: 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy epitomizes that tendency. Ursula Le Guin manages to make The Dispossessed, about a physicist named Shevek who leaves his isolated moon colony of Annares to pursue his research on the main planet Urras, one of the rare ones that fits sympathetic description of the workings of an anarcho-syndicalist society into a story that has merit on its own.

Le Guin is adept at inserting conspicuous phrasings that distinguish the anarchist society of Annares from contemporary language of Earth (acknowledging the so-called Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis that the structure of a language affects the way speakers conceptualize their world). Shevek’s daughter says, “you may share in the handkerchief that I use,” instead of “you may borrow my handkerchief.” Her characters are the sorts that are rarely featured prominently in fiction of any medium: introverted, revolutionary, scientific. When it comes to character development, she isn’t Tolstoy, but she gets the job done.

As most reviews note, a strength of the book is the critical view Le Guin takes of the anarchist moon colony. She refuses to make it a place without problems, without fear, without ignorance. It is a place still burdened by all the failings of humans. By analogy, the major themes of the book recall Franz Kafka‘s The Trial, from the obscurantist-religious reading, in which Kafka’s protagonist Joseph K. struggles to apply rational logic to a legal system that ultimately is not rational because of its attachment to an irrational power system. Le Guin does what Joseph K. could not; she replaces all state institutions and laws with a rational system based on a non-hierarchical, stateless society. But she details how power structures linger, and they are much like those described by Kafka. The social organization is still subject to individual anxieties, fears, and attempts to consolidate power. But her main character Shevek engages his own limitations, and challenges himself to overcome them.

Just like tellings of Josef K.‘s story, Shevek goes beyond what his friend Bedap thinks about the unenlightened power structures that have been built up in an anarchist society that had supposedly permanently abolished them all long ago, to realize that there is no guarantee of consistency or meaning in any society, and he breaks the hold of the sustaining myth (the very preconditions of law) of the functioning behind-the-scenes power structures that “really” keep Annares going. She drives this home by having Shevek’s mother argue — as Bedap’s rhetorical rival — to stop Shevek from communicating with the planet Urras about his physics theories. Eventually, Shevek breaks the hold that the mother, and the belief that anything external to his mind provides meaning to his existence.

Take the following passage about the presence of police and military hierarchies. Not only does Le Guin convey an awakening and a rising consciousness in Shevek, but she concretely explains how means are inseparably tied to ends in social structures:

“In the afternoon, when he cautiously looked outside, he saw an armored car stationed across the street and two others slewed across the street at the crossing. That explained the shouts he had been hearing: it would be soldiers giving orders to each other.

“Atro had once explained to him how this was managed, how the sergeants could give the privates orders, how the lieutenants could give the privates and the segeants orders, how the captains . . . and so on and so on up to the generals, who could give everyone else orders and need take them from none, except the commander in chief. Shevek had listened with incredulous disgust. ‘You call that organization?’ he had inquired. ‘You even call that discipline? But it is neither. It is a coercive mechanism of extraordinary efficiency — a kind of seventh-millennium steam engine! With such a rigid and fragile structure what could be done that was worth doing?’ This had given Atro a chance to argue the worth of warfare as the breeder of courage and manliness and the weeder-out of the unfit, but the very line of his argument had forced him to concede the effectiveness of guerrillas, organized from below, self-disciplined. ‘But that only works when the people think they’re fighting for something of their own — you know, their homes, or for some notion or other,’ the old man had said. Shevek had dropped the argument. He now continued it, in the darkening basement among the stacked crates of unlabeled chemicals. He explained to Atro that he now understood why the army was organized as it was. It was indeed quite necessary. No rational form of organization would serve the purpose. He simply had not understood that the purpose was to enable men with machine guns to kill unarmed men and women easily and in great quantities when told to do so. Only he could still not see where courage, or manliness, or fitness entered in.”

So, this is a masterful novel, really as good as anything in science fiction.

Evelyn McDonnell Interviews Richard Goldstein

Link to an interview of Richard Goldstein by Evelyn McDonnell about the book Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the ’60s (2015):

“Live Through This: A Pioneering Rock Critic Looks Back with Love and Sorrow on the 1960s”

Sebastian Budgen – A New “Spirit of Capitalism”

Link to a review of Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello’s book Le Nouvel esprit du capitalisme by Sebastian Budgen:

William Davies – We Are All Just Rats in a Cage

Link to an excerpt from the book The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being (2015) by William Davies:

“We Are All Just Rats in a Cage: How the 1 Percent Profits From Your Misery”

Bonus link: “The Happiness Industry and Depressive-Competitive Disorder”

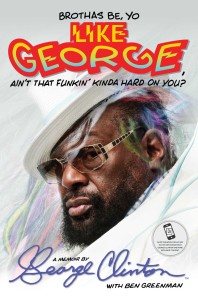

George Clinton – Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard on You?

George Clinton With Ben Greenman – Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard on You?: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster 2014)

George Clinton, of Parliament–Funkadelic fame, has written his memoir in the “as told to” format with journalist Ben Greenman. This gives the book a narrative feel, as if gathered from a series of conversations or recorded monologues. It’s comparable to other memoirs in that format (Cash: The Autobiography, The Autobiography of Malcolm X). Fans of Clinton’s music will learn plenty about how his bands evolved. The accounts of some of his bandmates are a little selective. Though his friendship with Sly Stone in the 1980s and 90s is rendered well as a sympathetic portrait of another star on a downward slide still trying to forge his own way. The first parts of the book, recounting his early days in a hard-working touring band and the middle years as part of a colossal musical entertainment empire that evolves into a corporate “organization”, are snappy and engaging like most music memoirs of this sort, while the last part of book covering the later years (tales of old fart funkadelijunkie) are bitter and resentful and a bit less endearing, just like so many of these memoirs that chronicle the autumnal years when few(er) were listening.

Latter-day fans who think of Parliament-Funkdaelic as two sides of the same band may be surprised to learn how differently they evolved, meeting only for a brief window in time. Funkadelic established itself first, and the band was influenced by psychedelic rock. Clinton mentions the English rock supergroup Cream as an influence repeatedly, and The Beatles, and Jimi Hendrix. He had an appreciation for the white British invasion blues-rock bands, applauding their interpretations of black American blues. He talks about Funkadelic being a very democratic band into the early 1970s. But he also discusses those days like a businessman, never failing to mention how he watched the charts for ideas, made promotional connections in radio, and worked every angle on commercial terms. When Parliament takes off in popularity, Clinton jumps at the chance to be the frontman. He felt that to be really huge a band has to have a focal point. What he glosses over, though, is what the rest of the band thought about that. Clinton talks about some of the key members like Eddie Hazel, but others are mentioned more in passing. He addresses some of the splinter bands led by others with a sense of slightly condescending pity.

If you believe Clinton’s account — and you probably can’t believe all of it — he has been screwed royally on financial matters and he’s cleaned up his life just before writing this book. Still, he comes across as pretty defensive. He has a rationale for everything. Yet he works pretty hard to put those rationales across to the reader, while trying not to let on to those intentions and apologetics. He is also a bit hypocritical. He waxes on about how all music is adapted from other music. And yet, a good portion of this book is a rant about how he’s been ripped off, especially in the hip-hop era when DJs have frequently sampled Parliament-Funkadelic songs. On one page, he’s praising adaptations of old songs (without payment), on another he’s complaining how he hasn’t been paid for samples. Now, he makes some good points that sampling royalties shouldn’t be set up as they are, and should instead be proportional to the sales of the sampler. But his arguments are confused and rather self-serving, ultimately resting on nothing more than his whims and fancies. Some deserve compensation, and others not, and the two can hardly be told apart without Clinton’s infinite wisdom (read: unlimited discretion). He mentions the George Harrison/Chiffons copyright lawsuit, and defends the ridiculous outcome. Yeah, maybe Clinton fell in with some crooked people who haven’t compensated him and pocketed the difference. He makes that case. It is a fair argument. But the idea that anybody at all should be raking in royalties for their efforts of decades before, and that sampling isn’t a fair use that creates no need for royalty payments, have kind of assumed away a big part of the public policy issues.

The most interesting way to look at this book is to set aside Clinton’s own spin and put his hippie ideals into a sharper critical focus. Sure, he was into free love and all that, though pretty early on he tried to reveal the superficiality of much of the 60s counterculture, in terms of how it failed to fundamentally transform society. But doesn’t that critique apply to him as well? The book doesn’t go there, but it should have.

Clinton is fast to discard the democratic cooperation of Funkadelic to achieve bigger commercial success with Parliament. The question of what was surrendered in that process goes largely unexamined, and the assumption that big commercial success is necessarily an achievement superior to purely cultural cachet looms large over the narrative. He derides those who sought material possessions. Yet at the same time he talks about how he instead wanted to use his wealth from Parliament’s success to accumulate experiences. Social scientists have explored how developing “cultural capital” through exclusive experiences and the “nonproductive consumption of time” is just another mode of establishing social distinction, not really opposed to the kind of thinking that gives rise to conspicuous consumption of luxury items. This is a curious flaw in Clinton’s version of hippie ideals.

He blasts those whose message was about “pointing at a power structure and condemning it as they went about installing themselves at the head of a new one.” But again, his pleas for credit (and remuneration) for his past achievements kind of seek to locate himself at a particular position in popular musical history, which is to say in a hierarchy. When discussing a Funkadelic reunion project that required large payments to Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell, Clinton complains about how they wanted to be reinstated as co-leaders and acted like stars, lording that status over the long-time (yet non-famous) members of his working band. Who decided that Clinton gets to make these calls? Hasn’t the audience, for better or worse, decided that they want to hear Bernie and Bootsy more than the members of Clinton’s latter-day working band? Isn’t that really why Clinton recruited Bernie and Bootsy back in the first place? There is a tacit assumption that in spite of what the audience thinks he gets to be the center of the operation and, like a CEO, slot everyone else in the band into their “proper” place. Sound very hippie-like to you? Or were hippies always short-sighted capitalists at heart, evidenced by the way they later gave into the “me generation” and vapid 1980s Reaganomics materialism? Don’t expect Clinton to pause long on these questions, because he doesn’t.

No doubt, Clinton has made some great music in his long career. But was his autobiography published only because of his musical talent or did his relentless ability to self-promote have more to do with it? The man admits some faults and mistakes, for sure, but those admissions are limited mostly to things he feels like he has since resolved. The demons he hasn’t bested still lurk in the shadows, and those shadows seep into the pages of this book more than Clinton probably intended. It is good to have this available as Clinton’s side of the story, but there are other perspectives that need to be explored to understand the Parliament-Funkadelic legacy.

Black Armed Resistance

Links to books about black armed resistance in freedom movements:

Negroes with Guns (1962) Robert F. Williams

We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement (2013) Akinyele Omowale Umoja

Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms (2014) Nicholas Johnson

This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (2014) Charles E. Cobb, Jr.

The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement (2004) Lance Hill

The Deacons for Defense and Justice: Defenders of the African American Community in Bogalusa, Louisiana (2000) L. LaSimba M. Gray Jr.

Bonus links: “Kurdish Women’s Radical Self-Defense: Armed and Political” and “Statement of Support for Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police”