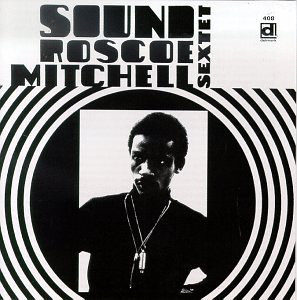

Pavement – Slanted and Enchanted Matador OLE 038-2 (1992)

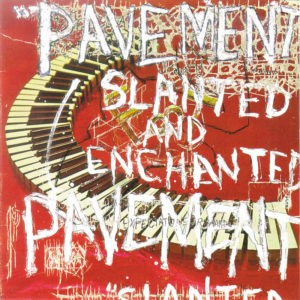

Pavement’s full-length debut album Slanted and Enchanted has remained a critical favorite decades on, sort of the archetype for the kind of indie rock it represented. It reveled in a “lo-fi” aesthetic with tons of slacker charm. Read most reviews of Slanted and Enchanted and you’ll probably be told one or more of the following: a list of influences (The Fall, etc.), personal details about the band members and the history of how the band was formed, and some personal anecdote about how the reviewer discovered or reacted to Pavement. You can read about those things elsewhere. I want to instead write about the cultural significance of Pavement in terms of what they represented in a larger cultural context of the time.

The 1890s were called the “gay 90s” and the 1990s were called the “cynical 90s”. Following a decade of brutally reactionary policy from the likes of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Helmut Kohl, cynicism in the 1990s was very much a kind of coping mechanism. In his important book(s), Kritik der zynischen Vernunft [Critique of Cynical Reason], Peter Sloterdijk described cynicism as “enlightened false consciousness”, a kind of purer strain of opium for the masses. That is just the right description for Pavement’s music. Read interviews with the band at the time and later, as well as any of the various books about 1990s “indie rock” and you’ll find much the same set of concerns about not “selling out”, staying “independent”, and so on. And yet, stop and think about what those things mean. It’s all an open acknowledgement of how shitty things are living under late capitalism. But the response is a kind of mild reformism (“economism” if you will), lessening the harsh impact and trying to stand apart from the worst excesses without really fundamentally changing anything. Their cynicism was a kind of self-preservation effort, by demonstrating an awareness of the shittiness all around, and thereby implying that they stood apart from it. Elaborating on more or less the same concept of disavowal, Mark Fisher wrote,

“Capitalist ideology in general, . . . consists precisely in the overvaluing of belief — in the sense of inner subjective attitude — at the expense of the beliefs we exhibit and externalize in our behavior. So long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange.”

Stephen Malkmus‘s lyrics are sort full of non-sequiturs and almost surrealist imagery. The lyrics, delivered with cracked, non-virtuoso singing, are a big part of what makes up the band’s sound. There is a charm about them. These seem like slackers worth rooting for. On songs like “Here,” Malkmus sings, “I was dressed for success / but success it never comes.” This is sort of what sociologists call “strain theory,” when there is a gap between social expectations and really existing conditions and actualities. Different songs here might represent different types of reactions to social strain: retreatism, rebellion, innovation. The second track, “Trigger Cut / Wounded-Kite at :17,” perfectly fits one of Sloterdijk’s phrases: “coquettish melancholy”.

The music is full of noisy guitar distortion. The drums are a lot looser than on later Pavement albums, and this album is altogether more legitimately lo-fi than later recordings. Alex Chliton‘s Like Flies on Sherbert is an important precedent for Pavement’s aesthetic in this regard.

Some of the songs seem like parodies of grunge era rock music. This is where the “enlightened false consciousness” angle gets a bit specific. Pavement seems to be parodying the “false consciousness” of others. But doing so doesn’t escape this false consciousness, and that was precisely Peter Sloterdijk’s critique of cynicism — it still retains a connection to that which it purports to reject, and what it does retain, subtly and unspoken, is the same lust for power and prestige, just through different techniques and strategies. Put another way, a parody of false consciousness merely steps away from the most extreme false consciousness while remaining within it, which is quite different than turning from the wrong path to the right path. If we look back to the song “Here,” it certainly contains a critique of the so-called “myth of meritocracy” of the neoliberal era, but it also displays a casual acceptance of it as well. There is a reference to joining in prayer (religion being the original “opium of the people”), and to waiting, as if someone else will swoop in and change things.

On this debut, Pavement was mostly channeling musical pop culture of the present and past. They had certainly studied up on everything good about 1980s “college” rock. But they were putting their own stamp on it all. That was evident with the album cover — a trashed re-purposing of an old album cover. Later on, Malkmus’ lyrics got a bit sharper. By the time of Brighten the Corners, he was witheringly good at capturing the existential anxiety of trying to manage socially imposed expectations, personal desire, ambition, and resigned acceptance of limited possibilities. But on this debut, the raw energy is a bigger factor.

While it is important to note the band’s cynicism, there was more to their music than just that. Actually, one of the very reasons they remain one of the most lauded rock bands of their day is that they used their cynicism to open up a space to slip in some rather earnest reflections on the sorts of anxieties and coping mechanisms that middle-class, educated white people tended to rely on in a time when opportunities were starting to diminish and expectations were being (somewhat forcibly) adjusted downward. Pavement didn’t rage and despair about it in a nihilistic way quite like, say, Nirvana. They took a more contemplative approach. The ironic distance and cynicism Pavement used was kind of a dead end (just like nihilistic grunge/alt rock). It accomplished the opposite of what it intended. But I think their music represents kind of a necessary wrong move, to enable those who followed to make the right moves — or, at least, better moves.

Well, I might as well succumb to one of the typical Pavement album review cliches, and talk about how I was introduced to them. In the late 1990s I was involved in student radio. A woman (Nora?) worked at the station who was middle-aged, and I think was in a graduate program at the time. Everybody loved her because she was one of those gracious, erudite types, who treated us young college kids with respect, lending her wisdom to us but seeking to learn from (and about) us too. When talking to her one day she admitted to having fallen out of the loop on what was the latest “in” music, and asked what band was like the new Pavement. I had never heard of Pavement at the time, so I had to admit I did not know. But her inquiry encouraged me to find out. Though I made only a cursory investigation at the time. I did keep hearing more about them though. At another school, a classmate of mine who knew I wrote music reviews for the campus paper asked what I thought about Pavement. His all-time favorite album was Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain. Then a few years later a friend got me a ticket to see James Carter‘s Gold Sounds project perform — this was a jazz band covering Pavement tunes. I felt somewhat bad for not sharing my friend’s deep knowledge and appreciation of the songs, even if I already had an interest in Carter. Anyway, now with a much deeper appreciation of Pavement’s music, I can say that Brighten the Corners remains my favorite of theirs, though Slanted and Enchanted is the runner-up and is definitely the place to start with this important 1990s rock outfit.