Link to an article by W.T. Whitney Jr.:

“Climate Change: What About the Marxists?”

Bonus links: “This Changes Some Things” and “Survival of the Richest”

Cultural Detritus, Reviews, and Commentary

Link to an article by W.T. Whitney Jr.:

“Climate Change: What About the Marxists?”

Bonus links: “This Changes Some Things” and “Survival of the Richest”

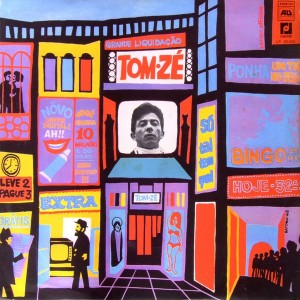

A guide to the music of Tom Zé. His professional musical career spanned half a century (and counting), though today many of his recordings are out of print — even in his native Brazil. What is available in the United States tends to skew toward his later recordings, which has the unfortunate effect of placing some of his finest material out of reach. His solo recordings are listed below divided into two time periods. His collaborations are listed separately — some being mere guest appearances while other are more extensive. Pursuant to the legend below, ratings are assigned to each, though Zé hardly has any bad releases so bear in mind these are just relative assessments. Links to other resources, including books and films, are provided at the end.

This is still under construction.

Born: October 11, 1936, Irará, Bahia, Brazil

Antonio José Santana Martins, who adopted the stage name Tom Zé, was born in the dry interior region of the Brazilian state of Bahia. He has described his hometown of Irará as “pre-Gutenbergian” (in reference to the inventor of the movable type printing press). His father won the lottery, which allowed his family to live comfortably in an otherwise poor and arid rural region. He moved to Salvador, the largest city in Bahia located along the Atlantic coast, to attend the University of Bahia. He studied music. He had an interest in composers like John Cage and Charles Ives. Although Brazil had a troubled legacy as a former Portuguese colony (and briefly was the seat of the Portuguese capital), and was the last country in the western hemisphere to ban slavery, social democratic president João Goulart made some modest reforms and the Brazilian universities recruited professors from Europe to bolster their musical (and other) programs. A military coup in 1964, supported by the United States, overthrew Goulart and installed a series of military “presidents” who ruled until 1985. Zé relocated to São Paulo, was associated with a collection of leftist intellectuals in the 1960s, and became part of the tropicália (A/K/A tropicalismo) movement, the most prominent members (tropicalistas) of which were mostly Bahian too. The (AI5) “coup within a coup” in 1968 brought harsher treatment of leftists and some of the tropicalistas. While considered a key part of tropicália, he also seemed outside it at the same time, never contained by its key precepts despite his obvious sympathies and contributions. His career faltered as the 1970s wore on. By the 1990s he was considering working at a gas station when he was approached by the U.S. musician David Byrne (of Talking Heads), who had come across a Zé record and later sought him out (with the help of Brazilian-raised musician Arto Lindsay) to sign him to a new label. Byrne was largely responsible for reviving Zé’s commercial career and introducing him to international audiences. Though in many respects, Zé’s albums on Bryne’s Luaka Bop label are somewhat over-represented in English-speaking countries.

Caetano Veloso has described Zé’s tenaciously archaic yet inventive approach to music as “bizarrely elegant” and his attitude (reflected in his music too) as having an “ironic, distant sense of humor” that is “at once intimate and estranged[.]” An incident on a plane that Veloso recounts is a fitting summary of a common effect of Zé’s music, when Zé made an absurd request for a particular drink (cachaça) on the plane, then, when it was not available, demanded the stewardess to stop the “caravel” (mid-flight) so he could leave, noting, “we were unnerved by the determination with which [the demand] was made, the sheer imposition of his will.” Veloso was impressed with how “the sincerity of [Zé’s] defiance exposed the absurd pretense of refinement” around him. This was in so many ways a fitting metonym for the entire tropicália movement. (The anecdote also recalls Bertolt Brecht’s short story “Geschichte auf einem Schiff [Story on a Ship]”). Recurring themes in Zé’s music involve tilting against colonial legacies (in the sense of Frantz Fanon) and making demands that emerge from leftist ideologies deemed impossible in his own time. Zé considers himself a performer of limited means. He has referred to at least some of what he does as sung and spoken journalism. In the 1970s he experimented with what can be called a homemade sampler, and has long utilized homemade instruments (like Harry Partch, or Tom Waits in the mid-1980s and early 90s).

After his comeback in the early 1990s, the influence of animated Brazilian folk dance musics from northern regions, like the forró and coco of Luiz Gonzaga and especially Jackson do Pandeiro, were more apparent in his own recordings. He continued working long after others would consider retirement. There is a tenacious sense of experimentation that is constant throughout Tom Zé’s career. He has toured internationally, though availability of his albums outside Brazil can be limited, even his most famous recordings.

Recorded:

Personnel:

Producer(s): João Araújo

Tier: ♻♻

Key Track(s): “São São Paulo”

Link to an article by Arun Gupta:

Bonus links: “Sorry, Bernie, We Need Radical Change” (this article does a good job summarizing the seemingly non-replicable quirks that led to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s primary election victory, but succumbs to reliance on self-defeating populist demonizations) and Crowds and Party

Link to an article by Zola Carr:

Bonus links: “Are We Governed By Secondary Psychopaths?” and “The War Inside Your Head” and “Mental Health and Neoliberalism” and “Are the Young People That Shrinks Label as Disruptive Really Anarchists With a Healthy Resistance to Oppressive Authority?” and “Social Service or Social Change?”

Link to a review of the TV show Corporate (2018- ) by Ed Hightower:

“Corporate: Offensive, Pointed Satire for a Change”

It is fair to say that Coroporate deploys kynicism.

Oblivians – Popular Favorites Crypt Records CR-065 (1996)

The punk movement in the United States took place almost entirely in the north. Drawing on the primitive rock of Detroit’s The Gories, Oblivians represented probably the south’s best contribution to punk-inspired rock. Popular Favorites is perhaps the band’s defining statement. The guitars are loud and crunchy. The rhythms are relentless. The lyrics are visceral piss-takes on the travails of a broke working band trying make a living, find romance, come to terms with their place in the world, and maybe also popularize some dance moves. Everything still sounds great more than two decades after it came out. The best cuts tend to be those with Greg [Cartwright] Oblivian on vocals. This album is now out of print but is available for streaming.

Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band – Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) Warner Bros. BSK 3256 (1978)

After a pair of widely panned albums in 1974, a 1975 collaboration, and a few years without any new albums — much of these travails the result of his entire backing band quitting in the face of Stalinist leadership tactics — the Captain returned amidst the punk era with one of his best. He had actually recorded an entire album (Bat Chain Puller) then lost control of the master tapes as part of a tangentially-related royalty dispute between owners of his label. He and yet another reconstituted version of The Magic Band then re-recorded some of the tracks, and some completely new ones, for a different label. Bat Chain Puller tracks omitted from Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) showed up in later re-recordings on Doc at the Radar Station and Ice Cream for Crow.

Anyway, Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) is something of a summary of many things the Captain had been doing in the 1970s along with a few new hot takes. The delivery is slicker, but, surprisingly, that generally works for rather than against the music. The album opens with “The Floppy Boot Stomp,” which signals that it was going to draw from the sort of idiosyncratic music that the Captain had been making in the Trout Mask Replica and Lick My Decals Off, Baby era but had abandoned in recent years. But the second cut, “Tropical Hot Dog Night,” channels Jimmy Buffett (and maybe also Flowmotion) in service of a statement of hesitant yet macho sexuality — a song reprised decades on by PJ Harvey as “Meet Ze Monsta.” A latin flavor later reappears on the song “Candle Mambo” too. This version of The Magic Band includes a brassy horn section that is somewhat unique, given that other recordings leaned more on woodwinds than brass. “Suction Prints” even sort of resembles punk — the first part of the song has a rhythm not too far off from Iggy Pop and The Stooges‘ hardcore punk B-side “Gimme Some Skin.” “Harry Irene” is a kind of ironic/nostalgic cabaret song (compare cuts like “Jean the Machine” and “Joe” on Scott Walker‘s ‘Till the Band Comes In). Sure, in “Owed T’ Alex” and “Apes-ma” (the one track held over from the original sessions), there are a few throwaway tracks here. But for the most part this album is great from top to bottom.

So how does this compare to the aborted Bat Chain Puller album (eventually released in 2012) this originally replaced? Well, in a way the original is even better — a little rawer, sparer and unified while still in territory that seems uncharted. But the Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) incarnation replaces prominent keyboards with its horn section that adds a new dimension, and the caribbean flavor of “Tropical Hot Dog Night” was completely absent on the original recordings. And the original lacked a song quite that good. The general eclecticism and fullness of the re-recordings is also something different and an asset in their favor. So maybe the new version of the album is better? Frankly, it is pointless to pick a favorite between Bat Chain Puller and Shiny Beast because they are both great. Beefheart fans are going to want to hear both (although the original recordings were officially released in 2012, they fell out of print quickly).

Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band – Bluejeans & Moonbeams Mercury SRM 1-1018 (1974)

Captain Beefheart released two album in 1974 on the Mercury label in the US and the Virgin label in the UK: Unconditionally Guaranteed and Bluejeans & Moonbeams. They both ventured into MOR (mainstream oriented rock) territory. Most Beefheart fans are appalled by both of these albums. The problem is that Beefheart had released some of the most inventive and abstract rock ever recorded. His turn toward smoothed-over commercial pop-rock is not something music snobs ever accept. On the one hand, Unconditionally Guaranteed is pretty dull, save for bits of a few tracks (“Peaches,” etc.) with horn sections that seem like less energetic versions of material off 15-60-75‘s Jimmy Bell’s Still in Town (1976). A clear parallel to the album’s overall turn toward mediocre conventions is CAN’s Out of Reach (1978). Unconditionally Guaranteed was recorded by the same Magic Band lineup that had worked with Beefheart for many years. They all quit after finishing the album. So Bluejeans & Moonbeams was recorded with any entirely new backing band. Some fans give the new band the derogatory nickname “The Tragic Band”. But all this is a bit wrong. Bluejeans & Moonbeams is a pretty decent album. Sure, it bears no resemblance to Trout Mask Replica. But so what? If this had been released under a new band name rather than being credited to “Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band” it seems likely many who hate it would have an entirely different opinion. In other words, the problem here is one of expectations. While this is definitely not one of the Captain’s best, with an open mind this fits comfortably alongside bluesy MOR rock of the mid-70s. This is definitely not a bad album — the same cannot really be said for Unconditionally Guaranteed. If you expect new frontiers to be crossed you will be disappointed by this. But ask yourself first whether such expectations are appropriate.

Link to an article by Victoria Law:

“Captive Audience: How Companies Make Millions Charging Prisoners to Send an Email”

This article buries at the end the official rationale for banning conventional mail (smuggling in drugs). But it also provides a simple explanation of new methods by which prisoners and their friends and families are exploited by the prison-industrial complex.

Bonus links: “9 Surprising Industries Profiting Handsomely from America’s Insane Prison System” and “This System Is a Moral Horror” and …And the Poor Get Prison

“what do democratic socialists effectively want? The rightist reproach against them is that, beneath their innocent-sounding concrete proposals to raise taxes, make healthcare better, etc, there is a dark project to destroy capitalism and its freedoms. My fear is exactly the opposite one: that beneath their concrete welfare state proposals there is nothing, no great project, just a vague idea of more social justice. The idea is simply that, through electoral pressure, the centre of gravity will move back to the left.

But is, in the (not so) long term, this enough? Do the challenges that we face, from global warming to refugees, from digital control to biogenetic manipulations, not require nothing less than a global reorganisation of our societies?”

Slavoj Žižek – “The US Establishment Thinks Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Is Too Radical – With an Impending Climate Disaster, the Worry Is She Isn’t Radical Enough”