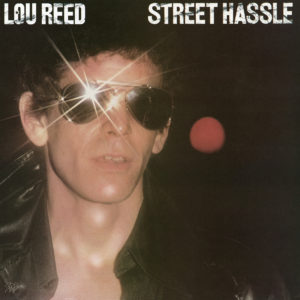

Lou Reed – Street Hassle Arista AB-4169 (1978)

Perhaps everyone is familiar with the saying, “two wrongs don’t make a right.” Well, along those same lines, Lou Reed’s Street Hassle might be seen as an attempt to make an album that succeeds by going about everything in the wrong way. The album is an amalgam of live and studio recordings. Reed and his band quote old songs, they use a muddy-sounding (and soon obsolete) recording technology, and seem to be against audience expectations. Reed’s lyrics are also dumb, guttural, defiant, and contrarian. Far from being a liability, this is why the album works! In fact, it might even be possible to say that songs like “Dirt” helped lay the foundation for the sludge rock of the 1980s — especially Flipper (who used a saxophone similarly on their quasi-hit “Sex Bomb”). The first side of the album is great, with the title track being one of the very finest moments of Reed’s entire career, and the second side is fairly good too.