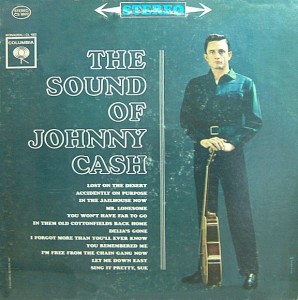

Johnny Cash – The Sound of Johnny Cash Columbia CS 8602 (1962)

After a few albums that tried to test the limits of Johnny Cash’s stylistic range and abilities — from the concept album Ride This Train to the retro country album Now There Was a Song! Memories From the Past to a second, drier gospel album Hymns From the Heart — he returns to the established folk-country sound of The Fabulous Johnny Cash and Songs of Our Soil with The Sound of Johnny Cash. While he is not trying to break any new ground, and there is not any standout single included, this remains one of his better early/middle period albums. It is a pleasantly mellow and likeable album that aligns the material and performances with Cash’s disposition as a singer raised on a farm but with some years of national touring behind him. He sort of honors his roots, yet also aims for something that has a touch of urban sophistication that stretches beyond those roots. By 1962 Cash’s voice had changed a bit, deepening and coarsening as a result of a steady touring performance schedule that left him with problems of chronic hoarseness. Those troubles with his vocal chords don’t surface on this album, but rather add a layer of complexity — turmoil even — just under the surface.

“In them Old Cottonfields Back Home” is a traditional folk song, and it just happens to ring true to Cash’s own upbringing on an Arkansas cotton farm. “Mr. Lonesome” with its vibraphone accompaniment and Cash singing at a lethargic pace, going into his lower vocal register, with light backing vocals, is pitch perfect for the album. Halfway between a smooth pop romance song and country heartbreak weeper it fits the hybridized city/country style that Cash had mastered. Then there is his first recording of the grim first-person tale “Delia’s Gone” (revived decades later with great success on American Recordings):

“First time I shot her

Shot her in the side

Hard to watch her suffer

But with the second shot she died”

With that song Cash was sticking to his fascination with murder and the dark side of life. A star of his stature might have been tempted to cast those interests aside and go exclusively with lighter fare — like Elvis around this time. Johnny Cash never did what might be expected, though.

Guitarist Luther Perkins is a crucial presence. As the music pushes toward urban sophistication, Perkins’ iconic boom-chicka-boom guitar picking is this primitive ballast that refuses to dissolve into the airy, consonant vocal harmonies. Yet that guitar sound is also an ideal foil for Cash’s vocal phrasing, allowing Cash’s singing to occupy a middle ground that moves confidently into the era of post-WWII prosperity without forgetting the grit, hard work and determination of a rural childhood. Cash’s background is honored while still being compartmentalized as a stepping stone to a role as an musical ambassador of sorts — most of Cash’s political views fit into the left-ish end of New Deal programs that accompanied the post-war boom.